While many eminent people of good standing and excellent reputation have been admitted to the Middle Temple, occasionally a rogue has disguised themselves long enough to be counted among the membership. Eventually their disreputable nature tended to reveal itself and they were summarily expelled from the Inn. This was the case for Thomas Montgomery, who not only got thrown out of the Society for his rowdy behaviour but went on to murder a man behind Middle Temple Hall.

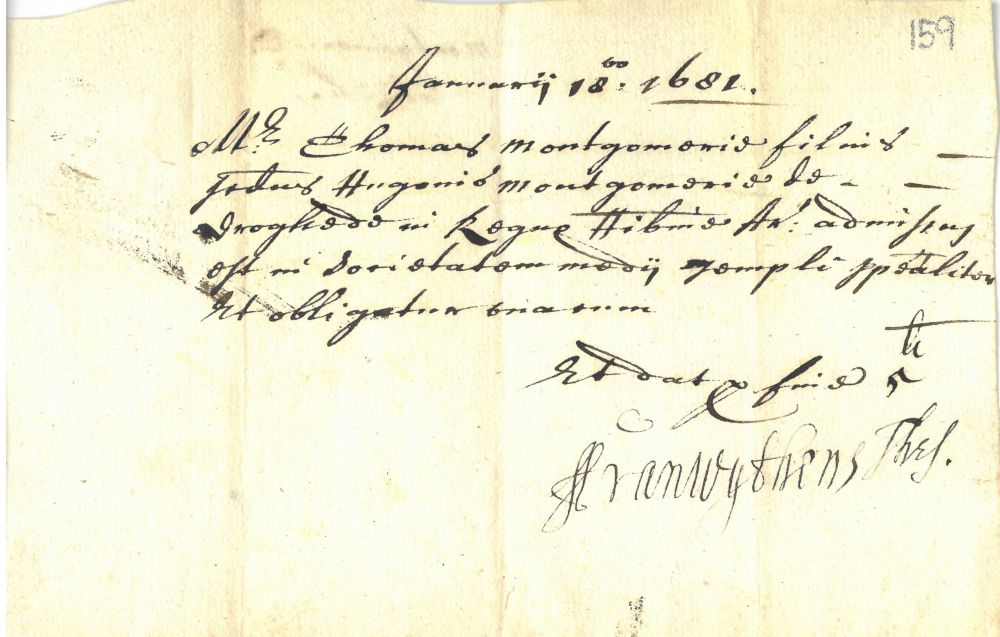

Admission record of Thomas Montgomery, 18 January 1682 (MT/3/ALO/15/159)

Originating from Drogheda, Ireland, Thomas Montgomery was admitted to the Middle Temple on 18 January 1682 and was of sufficient standing to be ‘Called of grace’ on 9 February 1683. Montgomery appears to have stayed in London after his Call as he was present during Christmas 1683 for an episode that outraged the Benchers. Despite annual orders prohibiting gambling and dice at Christmas, Montgomery, alongside a group of five other members, decided to violate this prohibition to the extreme. These raucous youths broke open the doors of the Hall, Parliament Chamber, the buttery and other offices and proceeded to hold a rowdy gaming Christmas with a group of non-members. Worse still, they occupied these spaces while wielding halberds and assorted other weaponry, making their removal and the reassertion of the rights of the Society over their property fraught with danger.

A seventeenth century German halberd in the Middle Temple’s collection of Arms and Armour

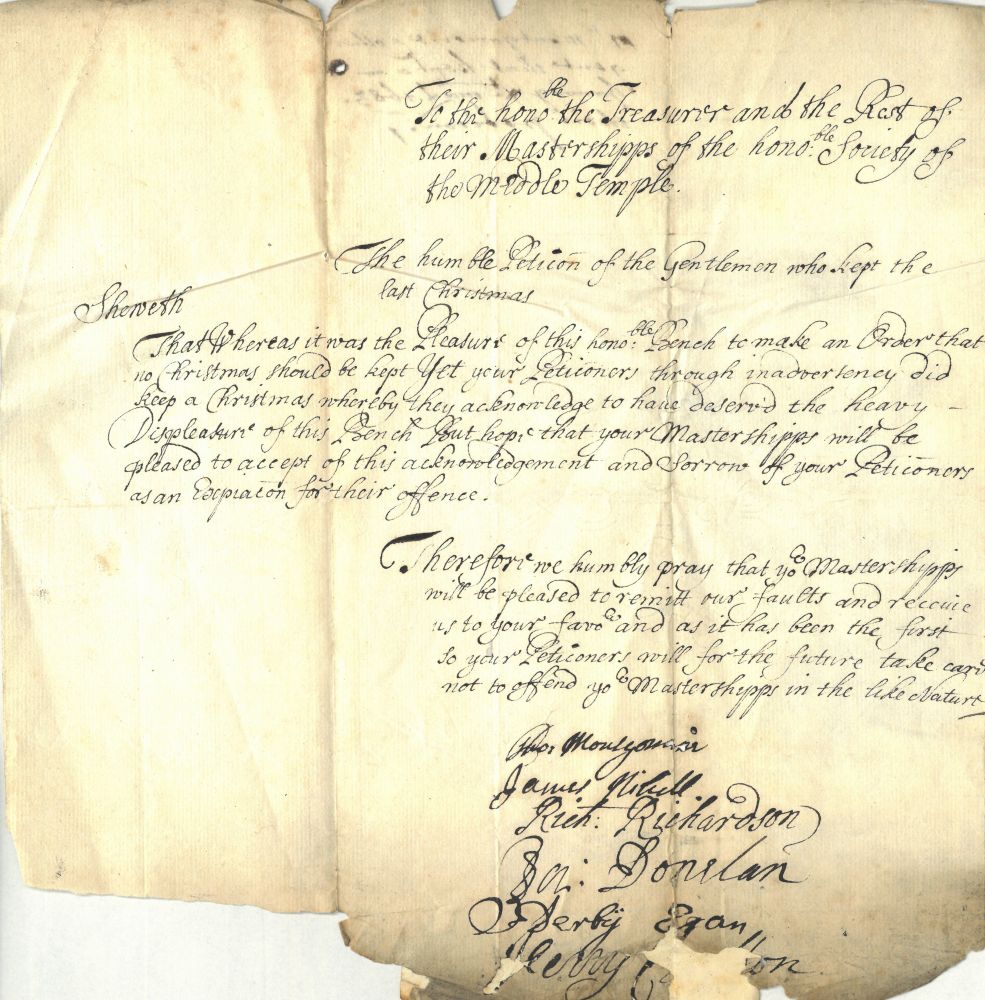

The gentlemen involved in this illicit party, if they had not at the time, soon came to realise the severity of their offense against the dignity of the Inn and its Benchers. In desperation, they submitted a petition to the Inn’s Parliament, downplaying their behaviour as ‘through inadvertency’ keeping Christmas, providing the excuse despite the order annually being fixed onto the screen. Notably, Thomas Montgomery was the first signatory of the petition – this could indicate that the petition was made at his instigation or that he was an acknowledged ringleader in the group. On 9 May 1684 it was ordered that all gentlemen who had participated in the escapade be expelled.

Petition submitted by Thomas Montgomery and the Christmas gaming party pleading for clemency, c.1684 (MT/21/1/117/3/10)

After his expulsion from the Middle Temple, Montgomery proceeded to fall further from grace. On 2 September 1684, for unknown reasons he went to the Rainbow Coffee House on Fleet Street, found one Walter Norman there and called him out to a duel. Despite their friends attempting to prevent the violent meeting, it went ahead behind Middle Temple Hall on 9 September. The two gentlemen drew their rapiers, and Norman received three wounds through his arm, one through the thigh and another small one on his hand. While it seems the duel was not intended to be a fight to first blood to satisfy or avenge honour, Norman died of his wounds on 16 September, possibly through blood loss or infection. The coroner was called the following day to view the body ‘lying there dead and slain’.

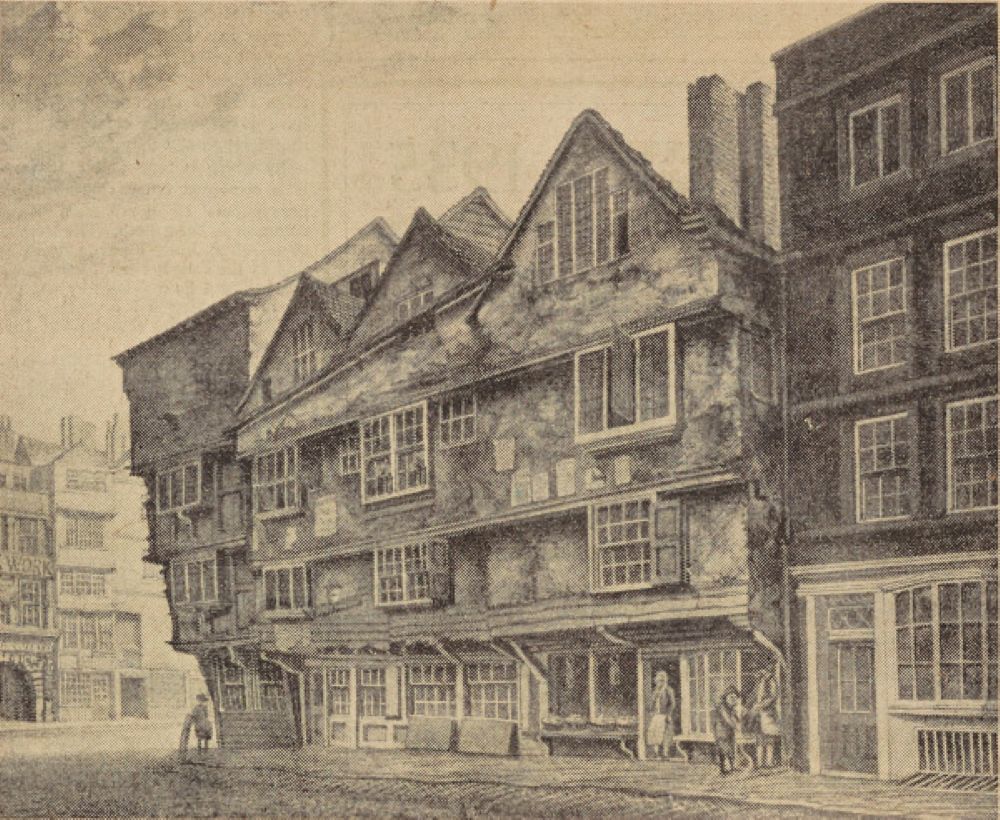

Reproduction of a painting of Chancery Lane by William Capon, 1798. Inner Temple Gate with the Rainbow Tavern to its right can be seen on the left-hand side of the image (MT/19/ILL/E/E12/13)

News of Norman’s death must have made its way to Montgomery as he surrendered himself to the courts. Mr Jones KC, in light of the fact that he had turned himself in, and that the witnesses for the prosecution were not ready to proceed, suggested that his trial be delayed. The delay lasted until the 10 December 1684. Despite Montgomery’s best efforts to prove that Norman’s death was accidental, he was found guilty of murder and sentenced to death. This would have been carried out by means of hanging and have led to the confiscation of all his property by the Crown. It appears, however, that his family was in favour with the King as they reportedly petitioned for clemency and Montgomery was granted a Royal Pardon for his crime of murder.

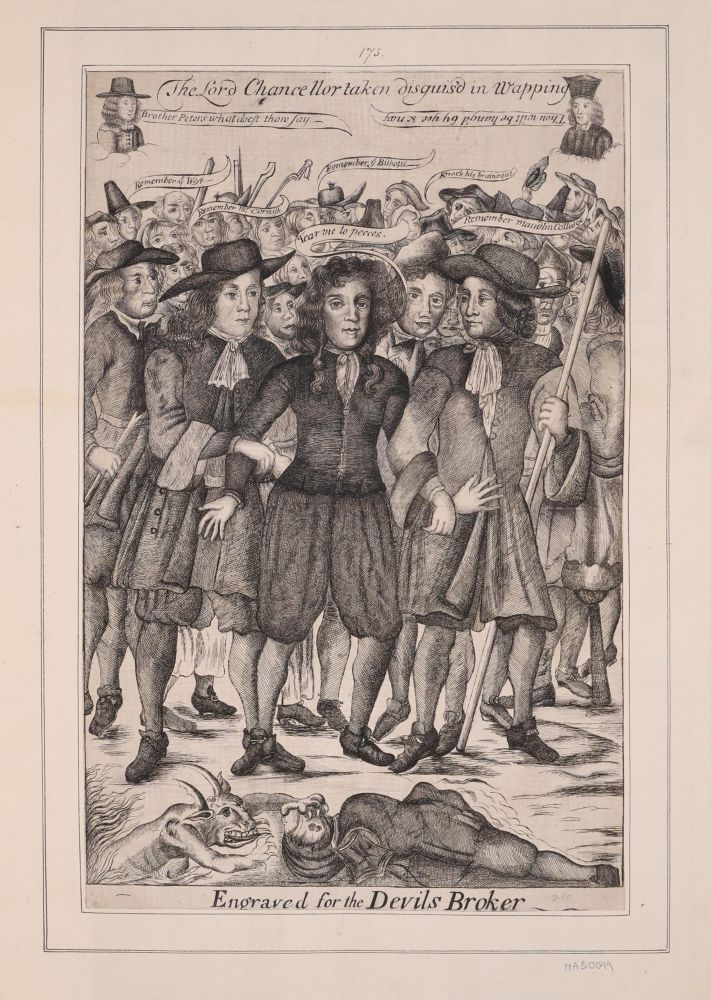

Print of the contemporary arrest of the Lord Chancellor at Wapping in 1688 © The Trustees of the British Museum

This incident would have caused a great scandal at the time, and despite Montgomery’s pardon, his presence was not likely to have been well received by respectable members of London society. In common with many people with ruined reputations, it is probable that he sought a fresh start for himself somewhere else. Perhaps utilising his family’s influence once again, he was granted a knighthood in 1687 by King James II and was made Attorney General of Barbados. This removed him to new society halfway across the world and gave him a chance to make a name for himself in an official government post.

Portrait of King James II as Duke of York

In practice, however, Montgomery ‘enjoyed little health… and little benefit from his office’. He failed to impress Lieutenant-Governor Stede, who in May 1697 very charitably reported that ‘through inadvertence he has been a little misled and engaged to a complacency’ and ‘he thinks me not his friend, as he has not liberty to do as he pleases’. By September 1688, it was clear that he was running out of patience with Montgomery, writing that he ’is a very troublesome man, who, by causing discontent wherever he goes, gives me much trouble, and is equally disorderly before me in Chancery, in the Council, and in the Courts of Justice, where he threatens juries to attaint them if they find against his clients. Many other things he does which cannot be passed without notice, but when I correct him he is discontented and thinks me his enemy, though I have hitherto done so in the gentlest manner possible. He regards me so little that I must deal with him more hardly since he will not reform’. Stede was still willing to allow him the chance to mend his ways at this point as he was not harming the peace and safety of the island, though he was suspected of being a spy.

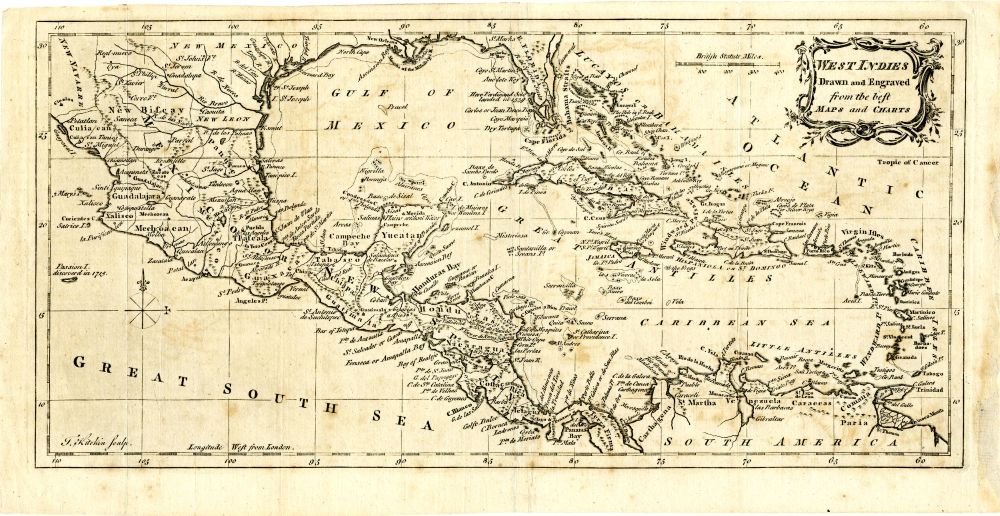

Map of the West Indies, showing the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea with the Islands, c.1734-c.1784 © The Trustees of the British Museum

The Glorious Revolution of 1688 caused King James II to flee to France and the Nine Years’ War (1688-1697) began between France and an anti-French coalition. The war expanded to the Caribbean colonies, with English, French and Dutch settlers engaging in armed conflict. Montgomery, ‘lately perverted from the Protestant profession by a French Jesuit’ and engaging in ‘popish practices’, was cast out of his office and arrested on 24 February 1689. Stede declared Montgomery ‘vicious and debauched’ and he was accused of going to Martinique to plot to deliver Barbados into the hands of the French. He continued to protest his innocence despite damning evidence against him and proposed various schemes via letter to the Lieutenant-Governor in the hope of regaining his favour, even drafting an order of the Governor of Barbados in Council for his release from captivity. Stede, no longer deceived as to Montgomery’s nature, refused to entertain his overtures and he remained in custody for two and a half years.

Print depicting a French marine entering the arms of death, c.1665-c.1719 © The Trustees of the British Museum

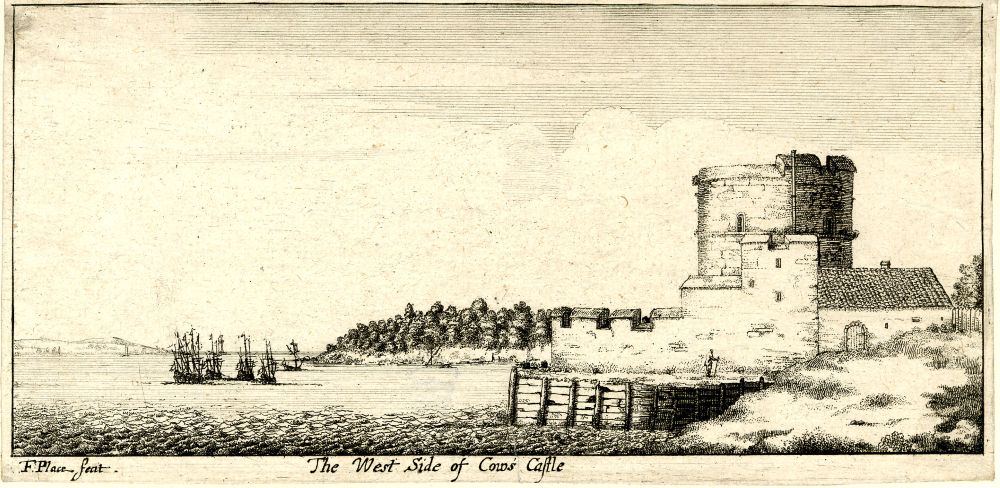

Even while imprisoned, Montgomery continued to caused trouble by writing malicious letters and pamphlets against the Lieutenant-Governor, and his male and female relations. He was transferred to the custody of George Hannay, Provost Marshal of Barbados, from 1 March 1691 and Hannay provided a report of his appalling conduct. He wrote that ‘I gave him three rooms in my house for respect to his dignity and all good usage but such was his strange lewd behaviour that I could not enjoy quiet in my own house and was obliged to keep a guard over him at my own expense, while his behaviour was so bad that the court passed several orders to prohibit him from receiving visitors, news ink or paper. On Governor Kendall’s account he had great hopes of release but has remained to my house until his departure when he refuses to pay my fees whereupon I distrained on his property. On my return he attacked me with a sword’. Having thoroughly disgraced himself, Montgomery was bundled away on the ship New Exchange in June 1691, arriving in Cowes on the Isle of Wight, by 1 September. He was subsequently granted bail on the understanding that he would appear before authorities to answer for his crimes.

Etching of Cowes Castle on the Isle of Wight as seen from the sea, before 1675 © The Trustees of the British Museum

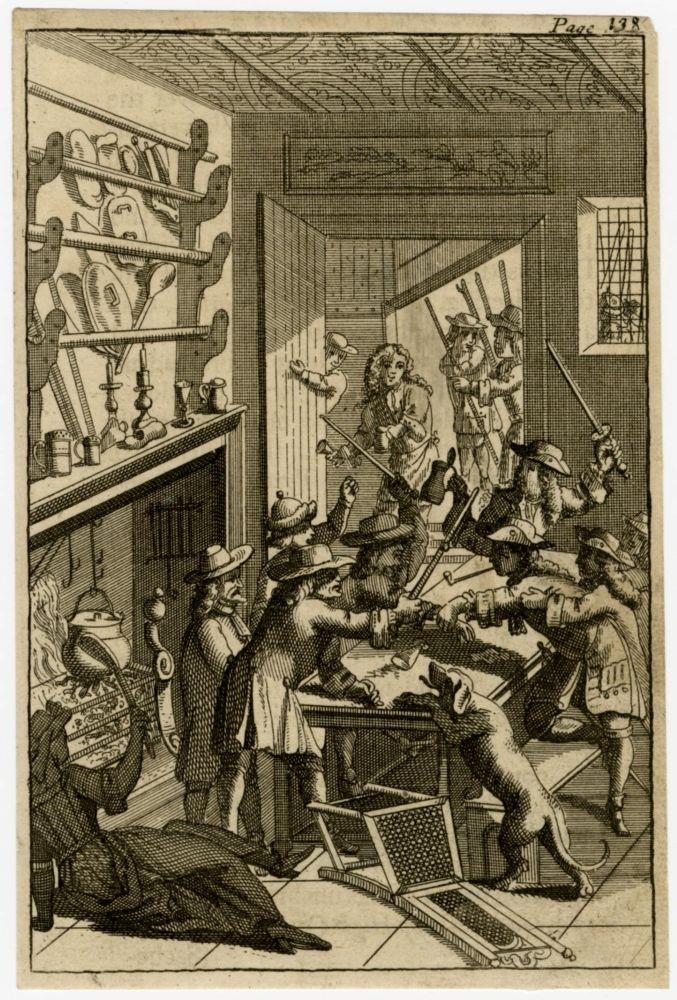

The Caribbean escapades of Sir Thomas Montgomery may not have been the last time that he entered the record books for all the wrong reasons. While difficult to conclusively link, an individual bearing his name appeared with a characteristic whiff of scandal in Athenrey, Ireland in 1707. On 23 July 1707 a petition was submitted to the Irish House of Commons detailing a battle over the office of Portreeve, a prestigious position in which a candidate was elected annually and oversaw the borough court. In 1705 Montgomery usurped the election, overturning the will of the burgesses, most of whom were Protestant. He raised a crowd, ‘most of them Papists’ and demanded the arms of the sitting Portreeve and elected successor, declaring that he ‘would send [the successor] prisoner to the Abbey to prevent his being sworn that day’. He turned out the Protestants and Sergeants at Mace from the town ‘and by his arbitrary proceedings, and by the terror of his party, kept [the successor] out of office and seized upon the Tolls and Customs of the said Town, and converted them to his own Use’. Lastly, he appointed forty new burgesses to the government of the town, who would likely have been his supporters. Montgomery’s election to the position was declared void and he was ordered to deliver up the symbols of the office to the legal Portreeve of Athenry.

Print of a politically motivated brawl in a tavern in Gracechurch Street, London, 1713 © The Trustees of the British Museum

Montgomery died in 1715 leaving five children that his wife had borne him illegitimately before their marriage in 1714, as well as property in Ireland, England and Barbados. His career at the Middle Temple had been of short duration, a decision that the Benchers were given no cause to regret by his conduct throughout his life. An impulsive man with a disregard of authority, loose morals and capable of murder when enraged, Sir Thomas Montgomery proved himself less than suited to a career at the Bar.