With the festive season's abundance of good food still fresh in mind, we continue to explore the history of catering and the kitchens at the Middle Temple. An earlier edition dove into the catering establishment of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and this month we move to the eighteenth century, and the changing role and pressures placed on the Chief Cook, the kitchen set-up, various foods served and complaints received.

Detail of a delivery of game in Fountain Court from ‘The Fountain in the Temple’ by Joseph Nickolls, 1738

At the turn of the eighteenth century, administration of the kitchen continued much as it had during the previous century. The Chief Cook was charged with providing daily dinners, also known as ‘commons’, out of his own pocket and then reclaiming the money from each gentleman. This allowed him to make a profit on commons but also placed the administrative burden of collecting money on him and created a risk of being greatly out of pocket if members were slow to pay their debts, which they often were. In 1725, however, there was a major overhaul in the organisation of the Inn’s catering. In addition to receiving a fixed annual salary of £20, the Chief Cook was provided an annual allowance of £15 for supplying the necessaries required to do the work of providing commons. This shifted the risk of unpaid commons from the Chief Cook onto the Inn itself.

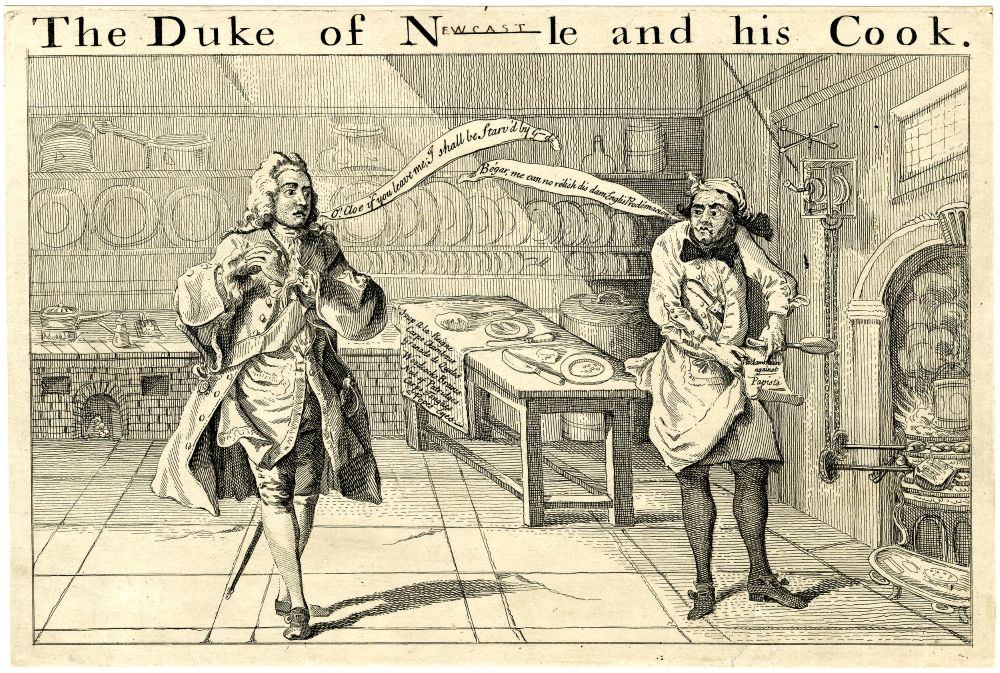

The Duke of Newcastle and his Cook showing a contemporary kitchen, 1746 © The Trustees of the British Museum

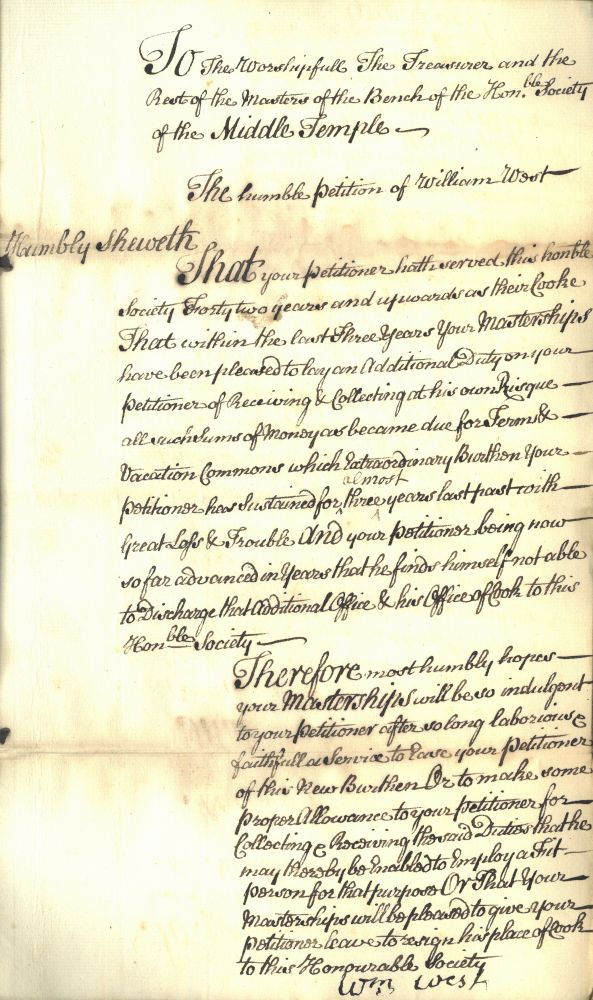

These changes would not last. By February 1747, the Society found that it was owed a great deal of money for commons due to ‘notorious negligence’ in collecting payment. It was decided that it would be simpler and less costly to the Inn for the Cook to once again take over responsibility for collecting the money. This was agreed by William West, the Chief Cook, in July 1747 and the following year he signed a new agreement that he would return to providing commons to the Inn ‘on his own account’. However, the following year he declared that he was unable to sustain the burden of these added duties in collecting commons and managing the catering finances. He had been Chief Cook for forty-two years at this point, and being ‘advanced in years’ decided to resign his position to the sub-cook, Robert Davis.

Petition of William West, cook, that he might be allowed to resign his position, 1749 (MT/21/1/1/1749/13)

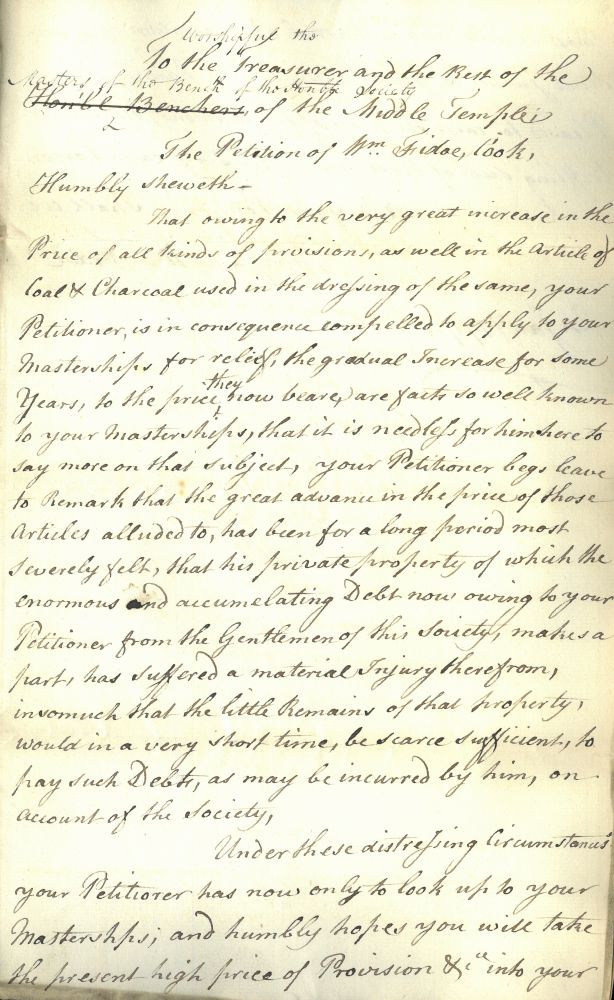

This financial arrangement continued until the 1790s, when the new Chief Cook, William Fidoe, came under significant financial pressure due to inflation caused by the outbreak of the French Revolutionary War, increasing fuel costs and poor harvests. In 1793, Fidoe petitioned the Inn’s Parliament for assistance. Although the price of commons had remained the same, there had been a huge increase in the cost of food supplies and fuel for the kitchen. He pleaded that ‘His private property, of which the enormous and accumulating debt owing to the petitioner from Gentlemen of this Society made a part, had suffered material injury therefrom’. He requested that the cost of commons be raised.

Petition of William Fidoe, the cook, to apply for relief due to the great expense of supplies, 1794 (MT/21/1/1/1794/5)

When this apparent injustice came to the Benchers’ attention, they ordered that a full committee be formed to examine the Cook’s accounts. The committee report was damning towards the Inn, stating that Fidoe ‘had not in any one year received the whole of what was due to him’ and that the Society ‘is bound by honour and justice to take some measures towards liquidating [the debt]’. Fidoe was duly paid out of the funds of the Inn, it was ordered that he was to be paid termly rather than annually, the cost of commons and repasts was raised and deposits of one guinea were required from the members for commons to try and prevent such a ruinous set of financial circumstances from occurring again.

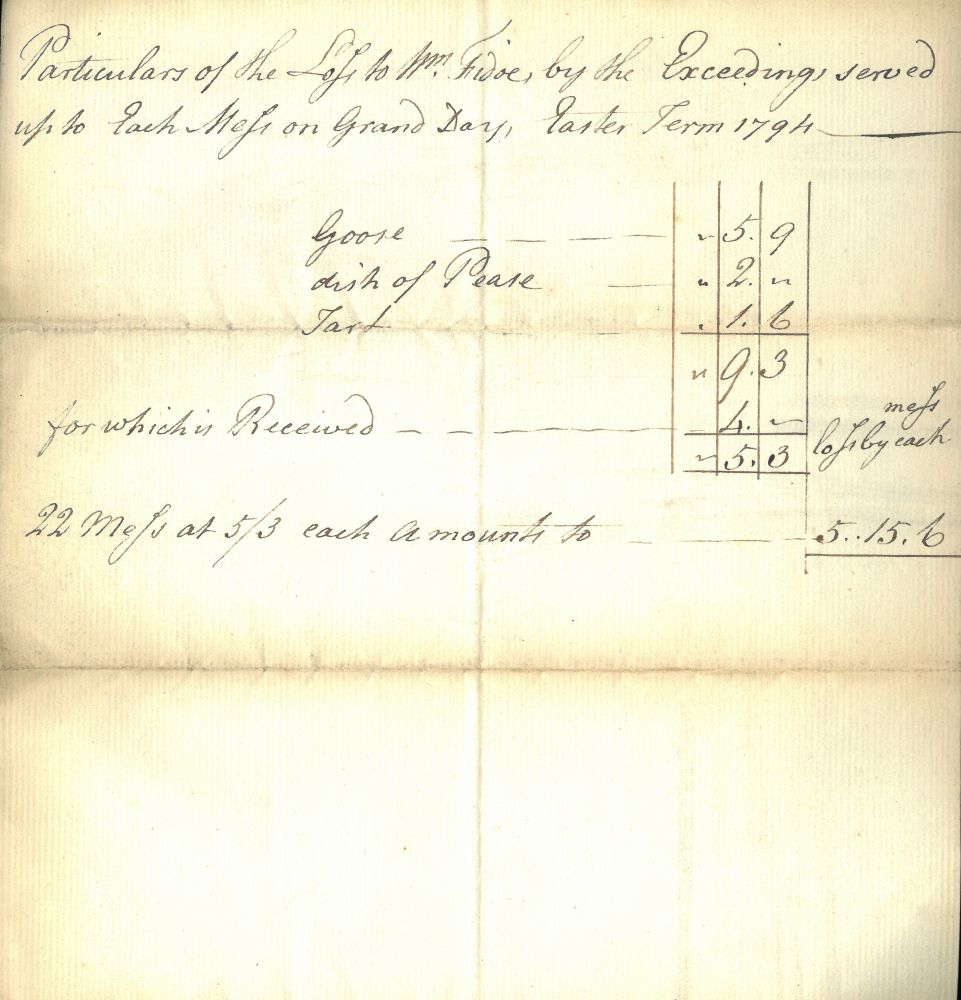

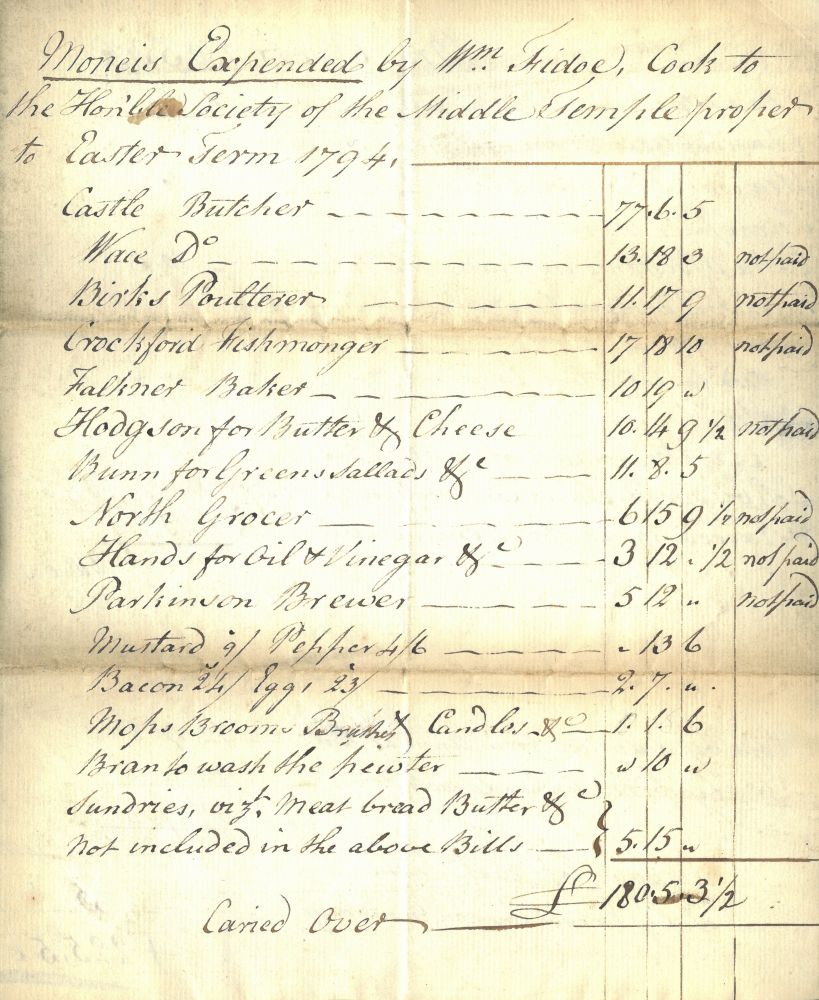

Particulars of the losses incurred by William Fidoe during Grand Day, Easter Term 1794 (MT/7/GCR/37)

As the administration of the kitchen was the domain of the Chief Cook, the Inn has very few remaining records relating to its day-to-day management. One bundle of papers survives, belonging to William Fidoe, perhaps as a result of their having been scrutinised by a committee of Benchers after Fidoe petitioned Parliament for relief. Among these are records of money owed to tradesmen such as butchers, poulterers, fishmongers, grocers and brewers, and for supplies such as butter, cheese, greens, salads, oil, vinegar, mustard and pepper. Cleaning supplies and other necessaries are also included, such as mops, brooms, brushes and candles and bran for cleaning pewter. The Chief Cook was also charged with providing fuel, such as charcoal, sea coal and faggots, for the numerous fires needed – not only for the large fires in the fireplaces, but smaller ones lit on the top of a raised brick or masonry counter-like structure called a potager, where coals and embers from the fire were shovelled into compartments on the top. Cauldrons or saucepans were placed on these using tripods or grates and this enabled more controlled, low heat simmering than a large fireplace.

Money paid by the Chief Cook William Fidoe to suppliers on behalf of the Middle Temple, to Easter Term 1794 (MT/7/GCR/37)

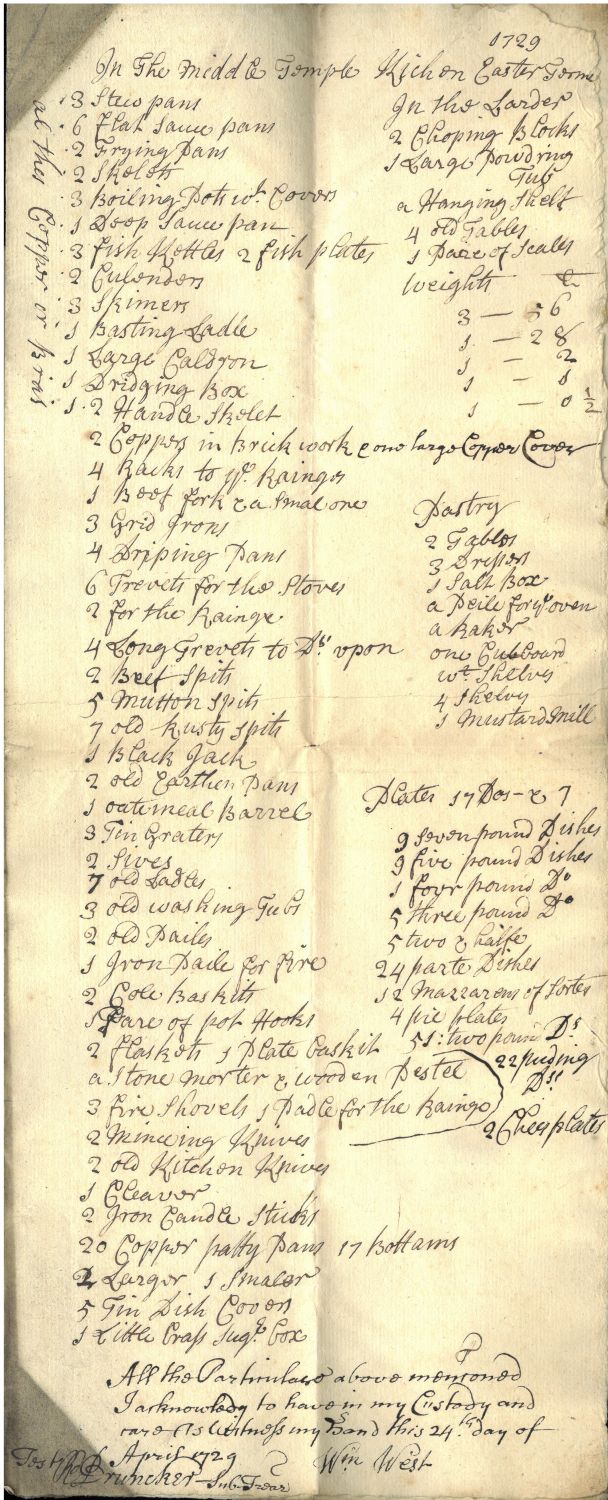

Several kitchen inventories survive from various points in the eighteenth century - usually created when there was a change in Chief Cook - and they illustrate evolution in the art of cooking during this period. At the start of the century, a 1703 inventory reveals a fairly primitive kitchen in contrast to what it would become. There was a long range and a short range – these were open fireplaces used for roasting meat, the larger generally used for large joints of meat, the shorter for smaller joints of meat, game and poultry. These would have been extremely important in a kitchen that served great quantities of meat daily. The long range had an incredible thirteen spits and there were an additional four spits for the short range. By 1729, after reforms to the kitchen, the Inn had switched from the spits to more modern ‘range racks’ or roasting racks on the fireplace, with two beef spits and five mutton spits surviving in good order and seven being described as ‘old rusty spits’. A tinman’s bill in 1724 also shows that this is when the Inn acquired a spice box and a sugar box. This may represent an upgrade to the Inn’s fare and the addition of more exotic flavours and richer food.

Inventory of all utensils in the possession of William West, Chief Cook, 24 April 1729 (MT/8/SMP/50)

William Fidoe’s inventory made at the end of the century shows a significant increase in the amount of kitchen equipment as well as more specialist items, implying an increase in the complexity of cooking during the period. Spits and joints of meat were still a large feature, but equipment for cooking fish, such as fish kettles and plates were now included. There were many more dishes, more specialist utensils and items such as jelly glasses, which reflected the new fashion for jelly desserts, elaborate gelatine confections made with fruit juice, sugar, lemon juice and wine. Many ingredients became more affordable throughout the century as Britain expanded its colonial empire. Lemons were one example found in the Inn’s receipts – these were an item of extreme luxury in the early eighteenth century, but they began to become more attainable in price from the 1730s onwards, and much more affordable in the 1780s. As they became more attainable financially, cooks would have been able to incorporate these exotic ingredients into more everyday cooking.

Silver lemon strainer from the Middle Temple’s silver collection, c.1730-c.1740

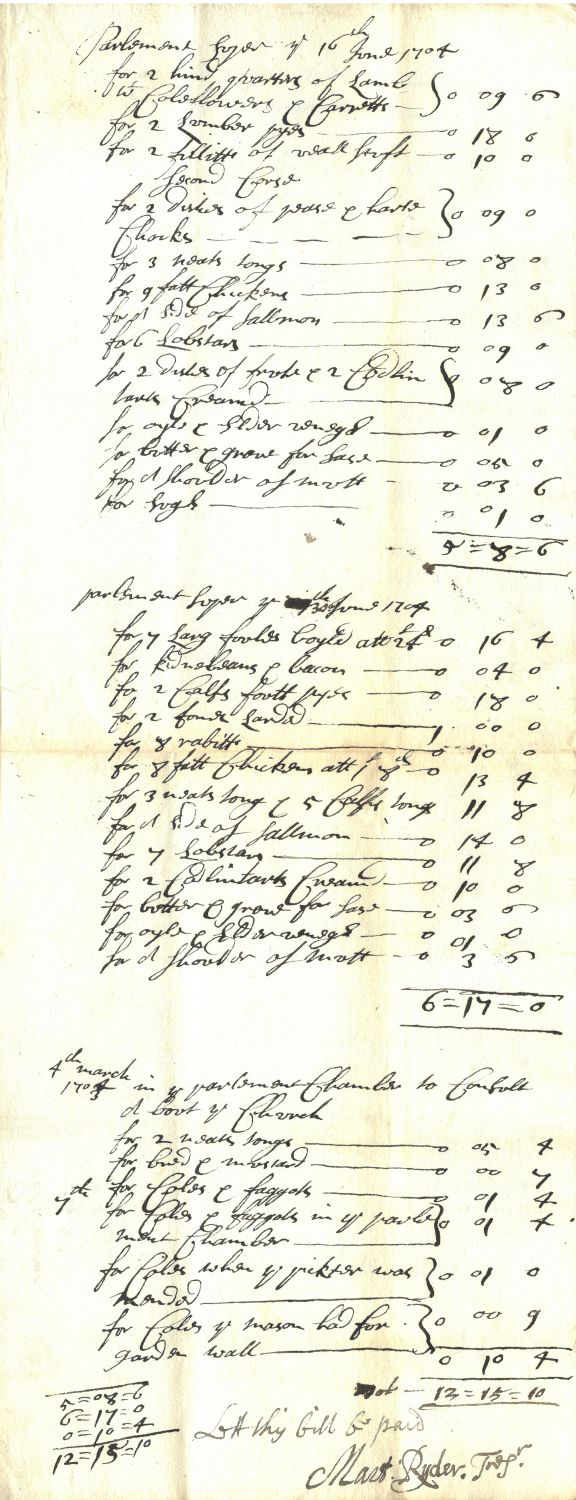

The most elaborate dishes and ingredients served at the Inn were saved for the Benchers and special occasions such as Grand Day. As this represented an additional expense above and beyond basic commons, the Inn assisted the Cook in financing the feast and bills for supplies survive within the Treasurers receipts. A receipt for a 1703 Parliament Supper shows an elaborate spread of meat, poultry, game, fish, seafood, citrus fruits, and apple tarts. During this era, quantity and variety were the fashion in elite circles. By the end of the century, menus were a lot more restrained in scope, with a much more limited variety of meat and fish, salads, and tea and coffee. This reflects the changing fashion for more complex preparation, presentation and flavouring which cannot be fully expressed by the kitchen’s bills alone.

Receipt for supplies for a Parliament Supper, 16 June 1704 (MT/2/TAP/31)

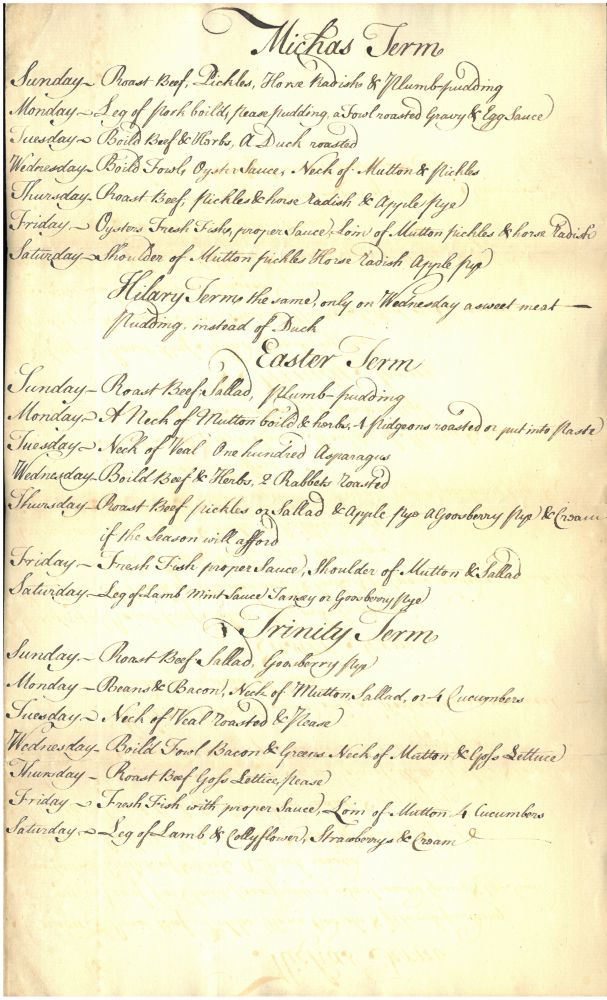

Meals shared by ordinary members were much simpler than those of the Benchers but still represented a high-status diet due to the large quantities of meat consumed. There was little variation in the menu, the same dishes being served every week in a single term, and when there was variety this reflected the seasonal availability of ingredients. A ‘Scheme for Commons’ in the papers of William Fidoe shows what was included in a typical menu in the late eighteenth century. These include simple but hearty dishes of roasted and boiled meat, poultry and occasionally game. A new addition to the menu in the later part of the century was variety of ‘sweet-meat puddings’, or desserts, these were not available every day and were sometimes substituted with a second variety of meat. The menu was highly seasonal with pickled vegetables being used during Michaelmas and Hilary terms due to the scarcity of fresh produce. Cream was added to the menu in Easter term ‘if the season will afford’ as the availability of dairy was tied to the calving season.

Scheme for Commons belonging to William Fidoe, Chief Cook, c.1794 (MT/7/GCR/37)

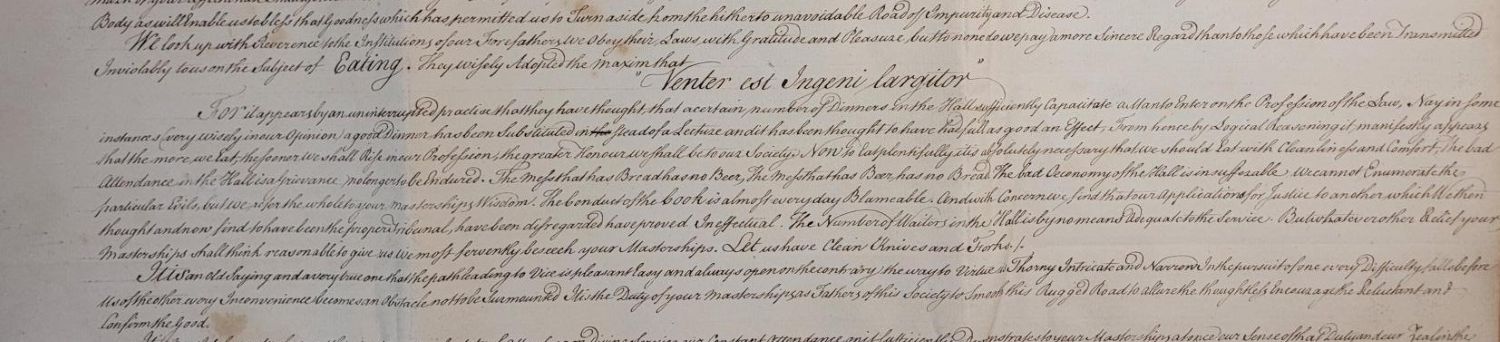

The daily commons of the Inns of Court was the fuel of the legal profession and when it did not meet expected standards, members did not shy away from complaining. In the latter half of the eighteenth century, a petition of the membership was submitted to Parliament listing many grievances, among them problems with commons. They collectively wrote that ‘a good Dinner has been substituted in stead of a lecture and it has been thought to have had full as good an effect, from hence by logical reasoning it manifestly appears that the more we eat, the sooner we rise in our profession, the greater honour we shall be to our Society. Now to eat plentifully it is absolutely necessary that we should eat with cleanliness and comfort. The bad attendance in the Hall is a grievance no longer to be endured. The mess that has bread has no beer, the mess that has beer has no bread. The bad economy of the Hall is insufferable, we cannot enumerate the particular evils, but we refer the whole to your Masterships wisdom’.

Extract from a petition of the membership to Parliament regarding the importance of good food and the poor provision of commons in Hall, eighteenth century (MT/3/MEM/55)

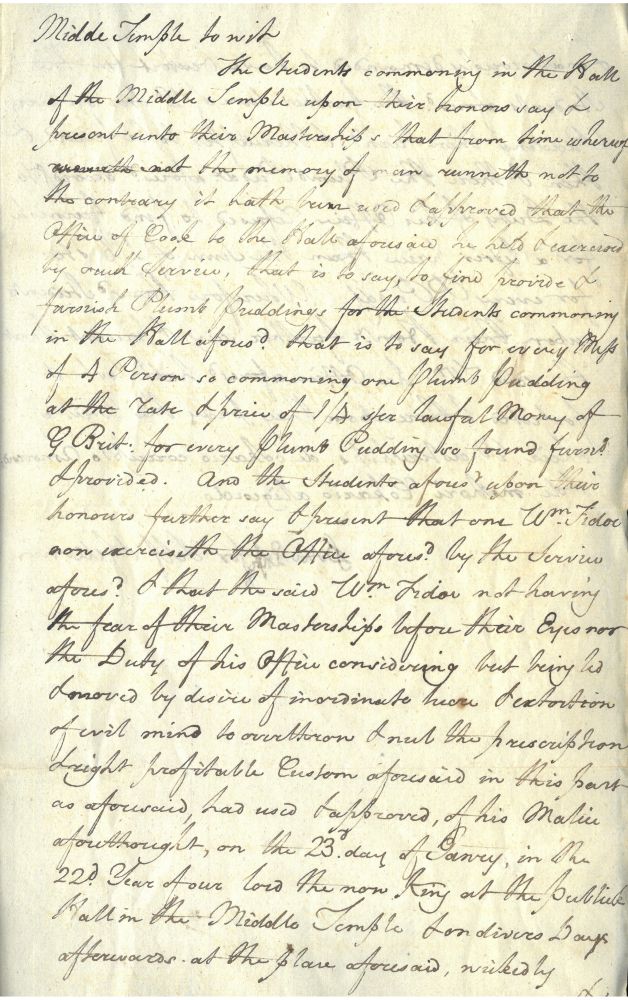

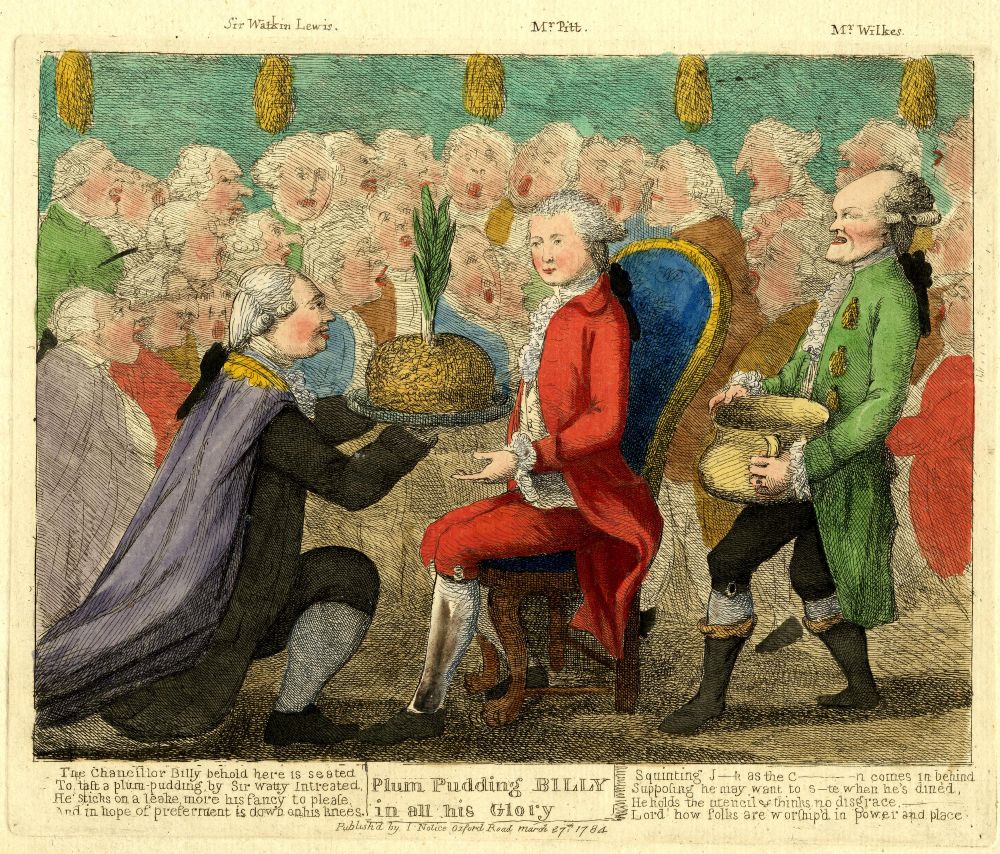

One complaint submitted about the food during William Fidoe’s tenure was in relation to the plum pudding that was regularly served during Michaelmas term. These plum puddings were the early precursor to modern Christmas pudding. Earlier in the eighteenth century they were a lot plainer than the modern variant, containing mostly suet, raisins, sugar, flour, eggs and salt. Later in the century more familiar elements such as, citrus, spices and brandy were added to recipes. These puddings would have been tied up in a cloth and boiled for at least four hours and one was provided per mess of four people. The students of the Inn accused Fidoe, of ‘wickedly and maliciously’ demanding the sum of 2d. for every plum pudding served. Further negotiations by the students led him to lower the sum, but this was not enough to prevent their anger, and they petitioned in vain that he be dismissed from his position. His position only fell vacant in 1800 after he died – he was buried April that year in Temple churchyard.

Complaint of students regarding the William Fidoe’s plum puddings, c.1794 (MT/7/GCR/37)

For much of the eighteenth century membership, food formed part of the heart of the Middle Temple – it nourished their bodies and the company they kept while dining nourished both their spirits and their minds. Most would have enjoyed simple but hearty fare consisting primarily of cuts of meat, a luxury confined to wealthier classes, and seasonal vegetables. By the end of the century, more elaborate ingredients, such as sugar and citrus fruit, were beginning to make their way into the daily fare, with some items paving the way for the festive Christmas menu of today.

Print of William Pitt being served plum pudding at a City feast, 27 March 1784 © The Trustees of the British Museum