By virtue of its proximity and joint freehold of the former lands of the Knights Templar, the Inner Temple is the Inn of Court with which the Middle Temple has necessarily had the closest relationship. While relations have remained productive and cordial throughout much of the history of the two Inns, there has occasionally been a rivalry that has erupted at certain points into discord. Some of this disharmony has occurred due to the question of precedence between the societies, with the mysterious origins of two separate ‘Temple’ Inns of Court giving rise to the notion that one of the Inns could be of greater antiquity than the other.

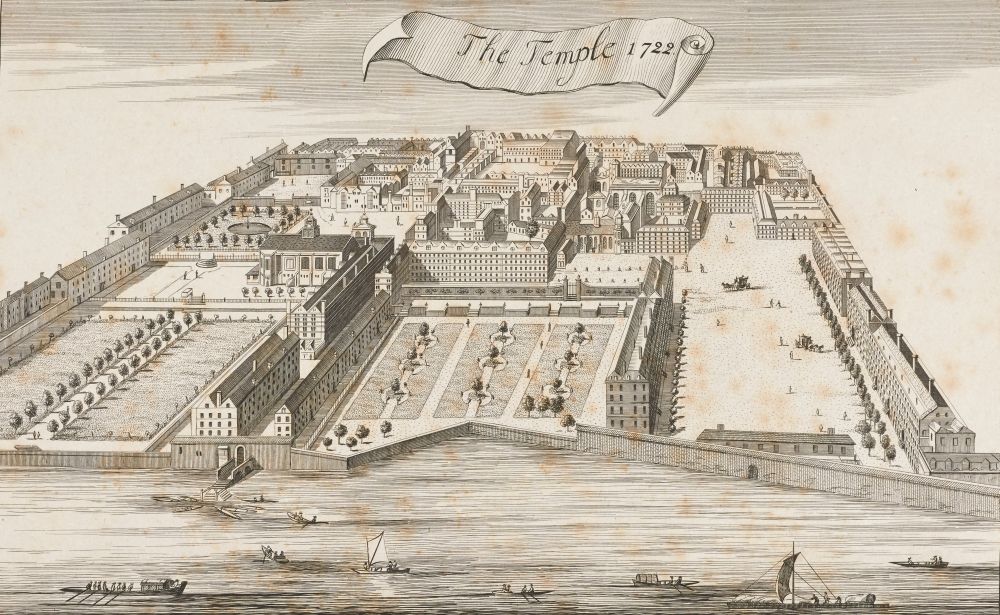

View of the Temple, 1722 (MT/19/ILL/D/D8/29)

The precise origins of the two separate organisations of the Middle Temple and the Inner Temple remain unclear due to the sparsity of surviving documentary evidence from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Over at least the last three centuries a debate has continued over whether the Temple was always divided into two societies or if they were a single organisation that split in two. The earliest surviving evidence for the two separate organisations, rather than members merely being named as originating from ‘the Temple’, comes from the record of a Call of eight Serjeants-at-Law, an elite status afforded to senior barristers, later superseded by that of King's / Queen's Counsel and now obsolete, in Michaelmas term 1388. The writer of the document indicated the origin of the incoming Serjeants - two came from ‘Greysynne’, five from ‘interioris Templi’ and one from ‘medii Templi’. The eminent legal historian John Baker suggests that it is likely that the Inns originated as two sets of lawyers, who each took out separate leases of pre-existing areas and buildings of the properties of the Knights Templar, and that they had always been two separate societies. If this is the case, it is possible that the Middle Temple and Inner Temple were in existence in some form prior to their move into the Temple.

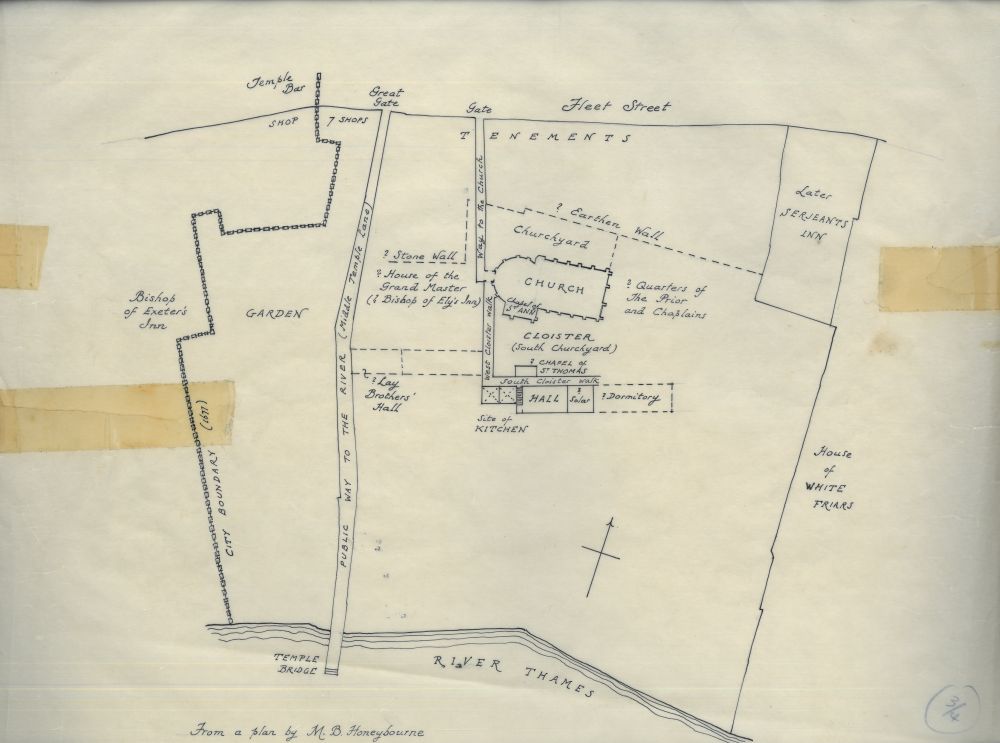

Plan of the medieval Temple precinct, showing a Hall to the south of Temple Church, and a second ‘Lay Brothers’ Hall’ on the east side of the road that became Middle Temple Lane, 1952 (MT/15/CAG/2/1)

Although initially both simply neighbouring tenants to the same landlord, the Middle Temple and the Inner Temple were formally bound together in 1608. This was the year when King James I granted a charter to both Inns, giving them joint ownership over their land and properties. One of the conditions in this grant was that both Societies became responsible for maintaining Temple Church, including providing for the Master of the Temple, and this joint responsibility necessitated a co-operative relationship and regular meetings between the Benchers. Many meetings took place in the neutral ground of Temple Church, and matters discussed included the Master of the Temple’s right to certain rents and burial fees, repairs to the causeway leading to Temple Stairs, the upkeep of Middle Temple Lane and arrangements relating to the watchmen of the two Inns. Meetings between the societies eventually became formalised as an official ‘standing committee’ in the first half of the nineteenth century. However, coinciding with the time that the Inns’ local authority functions began to be delegated to organisations outside of the Temple in the mid-nineteenth century, the ‘standing committee’ appears to have dissolved. Representatives of the Inns still formed joint committees for specific projects, but the regular meetings for co-operative governance of the Temple precinct appear to have come to an end.

![Copy resolution of the Inner Temple Benchers regarding the election of Benchers to the Standing Committee for the Consideration and Regulation of all matters relating jointly to [the Society of the Inner Temple] and the Society of the Middle Temple, 28 May 1799 (MT/1/MPA/10)](/sites/default/files/inline-images/3%29%20MT_1_MPA_10_0.jpg)

Copy resolution of the Inner Temple Benchers regarding the election of Benchers to the Standing Committee for the Consideration and Regulation of all matters relating jointly to [the Society of the Inner Temple] and the Society of the Middle Temple, 28 May 1799 (MT/1/MPA/10)

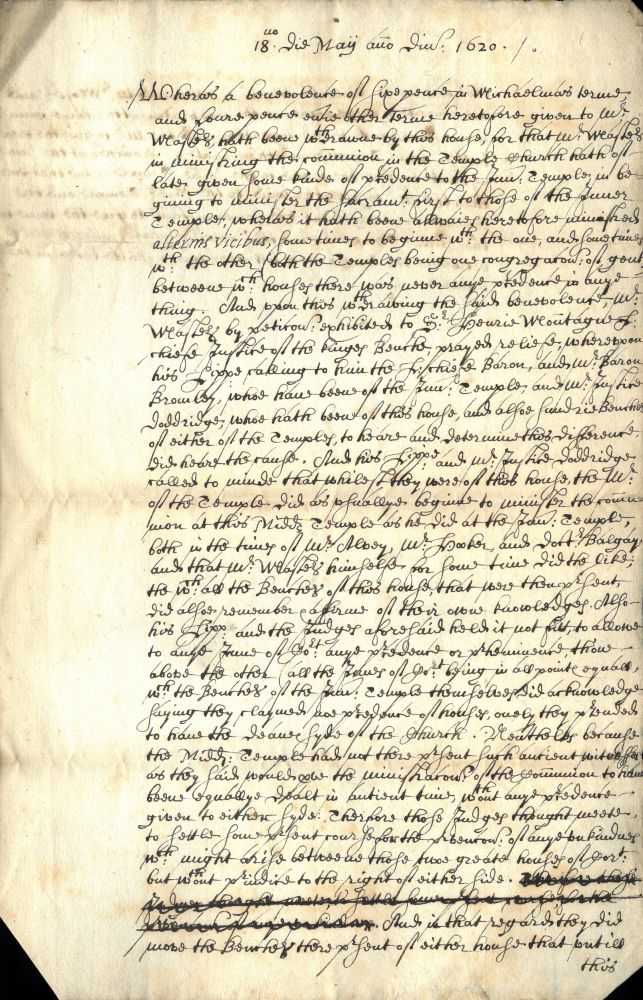

Despite an overarching spirit of civility prevailing between the Middle Temple and the Inner Temple, as in most long-standing relationships occasional quarrels arose. Questions of precedence have twice caused great consternation among the Benchers. The first recorded incident arose in 1620 in relation to the order in which communion was given to members of the two Inns at Temple Church. Inner Temple were given communion first by Thomas Masters, the Master of the Temple, and the Middle Temple Benchers felt insulted by this apparent favour. In protest they withdrew the Inn’s contribution to the Master’s allowance. Masters petitioned Sir Henry Montagu, Lord Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, for the restoration of his allowance, and Montagu called the Lord Chief Baron before him as well Benchers to represent both Inns, to settle the dispute.

Portrait of Sir Henry Montagu, later 1st Earl of Manchester, c.1600-c.1650

It was resolved that it was ‘not fit to allow to any Inn of Court any precedence or pre-eminence the one above the other, all the Inns of Court being equal’. The Inner Temple stated that they ‘claimed no precedence of houses, only they pleaded to have the Dean’s side of the church’. The solution eventually reached was that that the Master was to give bread to the Inner Temple at the same time that the curate gave bread to the Middle Temple. The two clerics would then swap places and give wine to the opposite Inn. In this manner equality and the relationship between the two societies was preserved.

Order of Judges concerning the dispute over precedence given by the Master of the Temple to Inner Temple in receiving communion, 18 May 1620 (MT/15/TAM/43)

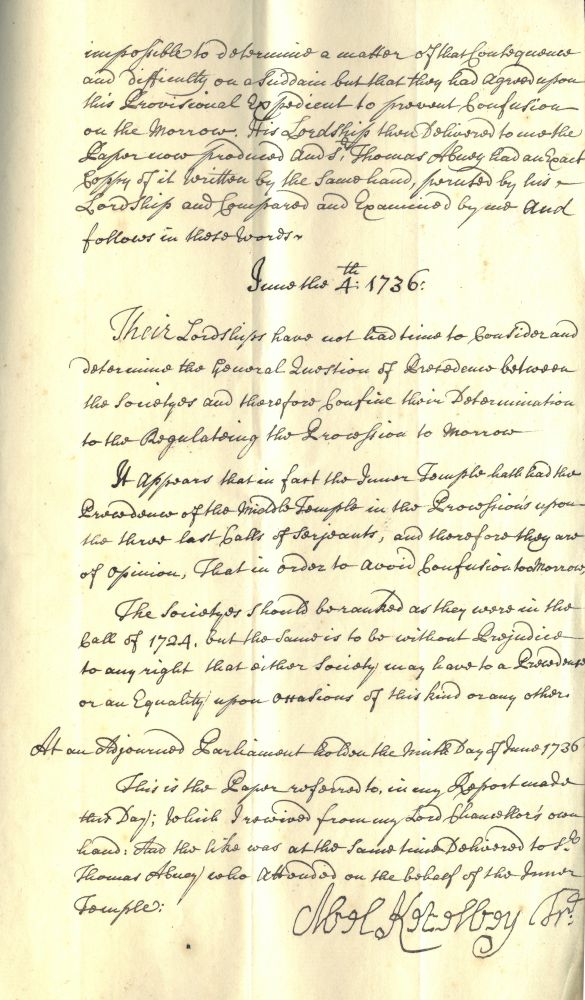

In 1736, a little over a century after the last such dispute, there was an unpleasant argument over the order of precedence during the public Call of fourteen Serjeants, nine from the Middle Temple, two from the Inner Temple. The ceremony was customarily held before the procession to Westminster and was appointed to take place in the Middle Temple by the Lord Chief Justice. However, Inner Temple announced their intention to take precedence in the procession and ‘in all such public processions’, which sparked outrage at the Middle Temple and led to a debate over which society was the older. This eventually descending to quibbling over the provenance of the arms of each society – Middle stating that they ‘enjoyed the ancient arms of the Knights Templars’ and that Inner ‘had assumed to themselves the Arms of a flying horse. We desired to know… when and how they got these wings to their horse? To which it was somewhat too hastily answered by one of the gentlemen in the opposition that their Pegasus was a much nobler creature than our own Lamb’. This dispute did not see the question of general precedence settled, but the Inner Temple was granted precedence during the Call of Serjeants as they had been first in the last three Calls of Serjeants.

Mr Treasurer Ketelbey’s representation about precedency, 9 June 1736 (MT/21/1/60/2/2)

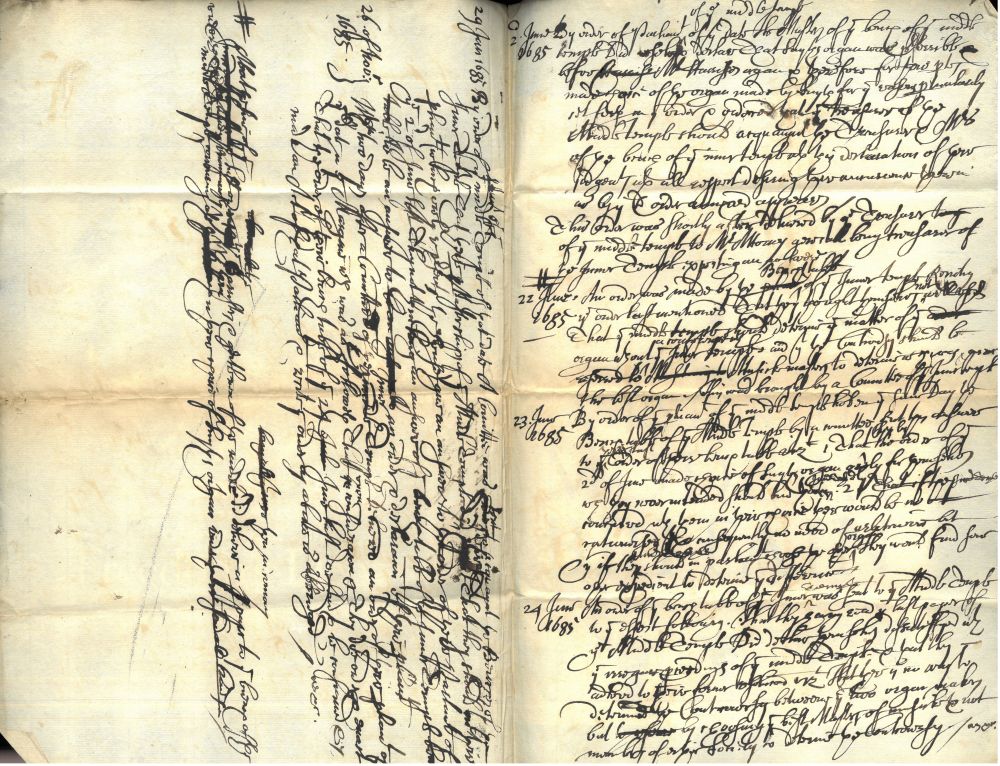

Another infamous incident of inter-Inn rivalry occurred the 1680s during the so-called ‘Battle of the Organs’. In 1682 it was decided that a new organ should be commissioned, as part of the refurbishment of the church by Sir Christopher Wren in the new English Baroque style, and a competition started between the organ makers Bernhard Smith and Renatus Harris. Both organs were set up in the chancel of Temple Church so that a comparison could be made between them. However, after a year in the church, an additional reed stop manufacturing challenge, and armed guards being installed out of necessity to prevent sabotage of the organs, the two Inns were still not able to agree which of the two was better.

Draft of the Inn’s case in dispute over the organ with the Inner Temple, 10 February 1686 (MT/15/TAM/101)

In June 1685, heartily tired of the whole affair, the Middle Temple released a statement in favour of Smith’s organ, but the Inner Temple continued to favour Harris’ organ. Eventually the decision was left to the Lord Keeper, Lord Guildford, who unfortunately died before he was able to give his decision. His successor, an Inner Temple member, Lord Chief Justice Jeffreys, came down on the side of Smith and the Middle Temple, finally concluding the conflict.

Reproduction print of George Jeffreys, 1st Baron Jeffreys, Lord High Chancellor of England and one of the Lords of the Privy Council, 1686 (MT/19/POR/403)

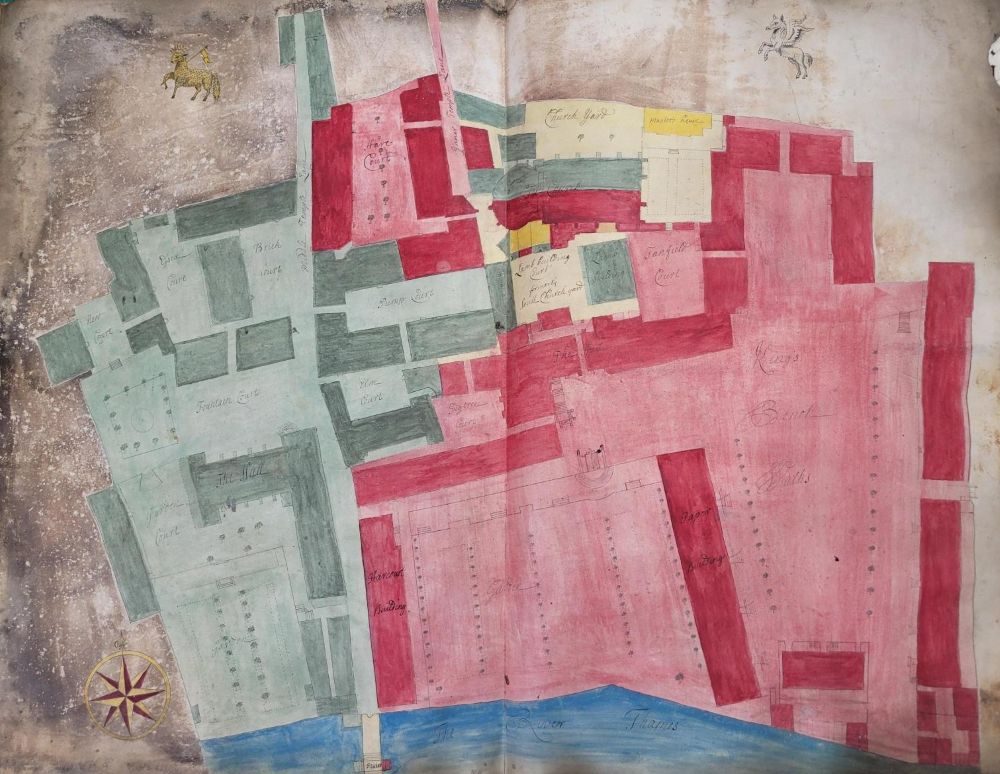

These incidents were minor quibbles next to the potential battleground created by the unclear division of the Temple lands. During the first century or so after the grant of the charter, the exact division of the land between the two Inns was ambiguous, which led to occasional friction. This came to a head in 1717 when the Inner Temple pulled down and rebuilt a building in Inner Temple Lane that the Middle Temple believed encroached onto their land – a disagreement that eventually led to court proceedings in 1721, which were settled in favour of the Inner Temple. Possible because of this case and earlier differences in relation to the title of land, both Inns mutually agreed in 1723 about the necessity of creating a ‘just partition of the soil and Buildings of both Societies in order that the bounds and limits thereof may be settled and ascertained’. Conveyancers were commissioned to create the Deed of Partition, which created a clear demarcation between the lands of the Middle Temple and those of the Inner Temple, and was duly signed in 1732. The meetings leading up to the signing of this great deed appeared to be very convivial – the Inner Temple’s records show that three bowls of arrack punch were ordered for one meeting and when the Inner Temple Benchers were invited to Middle Temple Hall to sign the document, wine was ordered to the significant cost of £12 2s.

Plan from the 1732 Deed of Partition (MT/4/5/2)

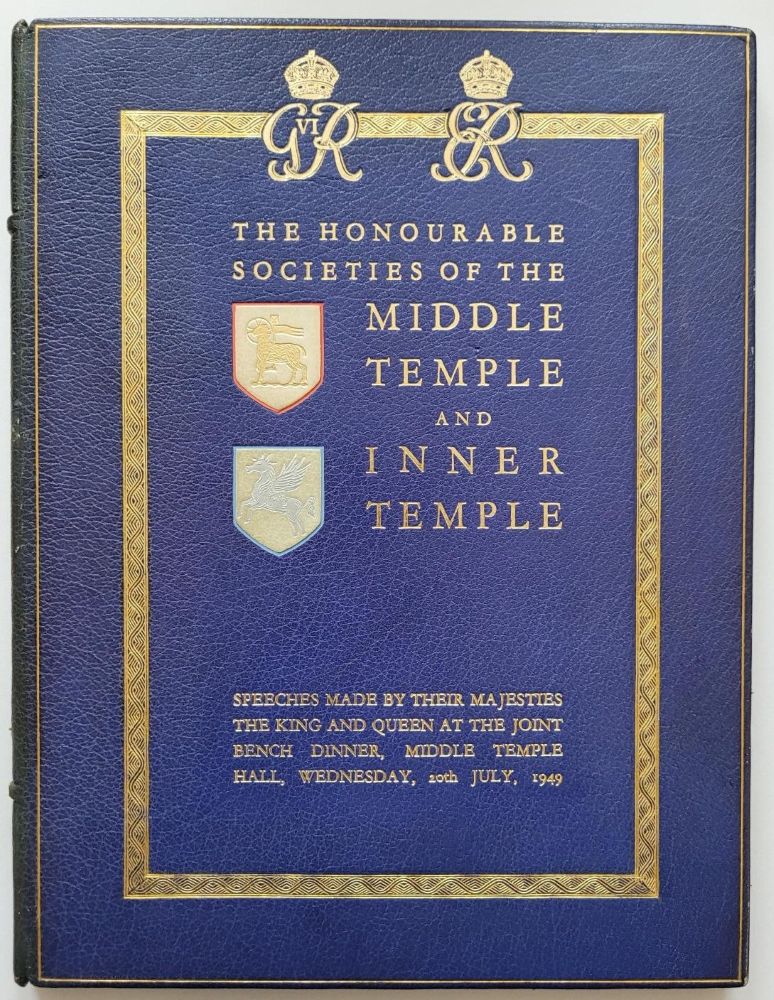

Despite occasional disagreements, the Middle Temple and Inner Temple came together in times of crisis – notably during the Second World War. After the Inner Temple was bombed on 25 September 1940, a raid which saw the destruction of Inner Temple Hall and many chambers buildings, Middle Temple Benchers informed their counterparts that they ‘would be pleased to place at the disposal of [the Inner Temple] all such facilities and hospitality as the Middle Temple could provide’. Middle Temple Hall was damaged in October 1940, with further injury inflicted during raids in 1941, but escaped total destruction. It was restored and was formally re-opened on 6 July 1949 by Royal Bencher Queen Elizabeth, who served as the Treasurer for the year. King George VI was also Treasurer of Inner Temple in 1949 and a Joint Bench Dinner was held in the Hall on 20 July 1949, overseen by the two Royal Treasurers. Speeches were given by both reaffirming the bonds of friendship between the two societies and proposing drinks to the health and prosperity of their opposite Inn. The Queen paid tribute to the Inner Temple, stating that ‘we look forward to the day when [Inner Temple] Hall may rise again to adorn its lovely setting, and to renew the tradition of hospitality for which it has long been famous’.

An illustrated commemorative book of the Joint Bench Dinner, 20 July 1949 (MT/7/ROY/6/4)

The 1949 Joint Bench Dinner was by no means the only occasion on which Benchers of the Inns dined together. By the late eighteenth century, reciprocal dinners were being held between the Benchers of both Inns. However, for reasons unknown the Middle Temple informed the Inner Temple that they were discontinuing this custom in 1790. The practice of holding regular dinners was only revived in the early decades of the twentieth century, with the inception of Amity Dinners, which were designed to strengthen the bonds of ‘fraternal amity’ between the Inns of Court. The first one of these hosted by the Middle Temple for the Inner Temple was on 5 December 1928. The Inner Temple finished rebuilding their Hall in 1959 and reciprocated the Middle Temple’s 1949 invitation in 1966 – this dinner also had royal guests, with Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh being in attendance. Amity Dinners continue between the two Inns to the present day, with the last one being held in 2025 and hosted by the Inner Temple.

Illustrated brochure of the dinner given by the Benchers of the Middle Temple to the Benchers of the Inner Temple, 5 December 1928 (MT/7/DNR/4/4)

Over seven centuries as next-door neighbours, the relationship between the two Temple Inns has developed and deepened, through changing historical contexts. While occasionally engaging in squabbles and disagreements, the Middle Temple and the Inner Temple have worked co-operatively to ensure the wellbeing of their members and the good governance of their institutions. When pushed by necessity, they have united against external threats, coming together in the spirit of fellowship to ensure their mutual survival.