Temple Church has undergone several renovations since its consecration in 1185, but none was as dramatic as those made necessary by enemy action in the Second World War. Like the rest of the Temple, the church and its congregation faced the challenges of restrictions and uncertainty at the beginning of the war and the horror of a world disappearing in flames due to enemy bombing. Despite these trials, both the clergy and congregation of the Church managed to find the strength and resilience to carry on amidst the ruins.

Postcard showing the interior of the Round Nave of Temple Church before the War, 1930 (MT/19/ILL/C/C5/51)

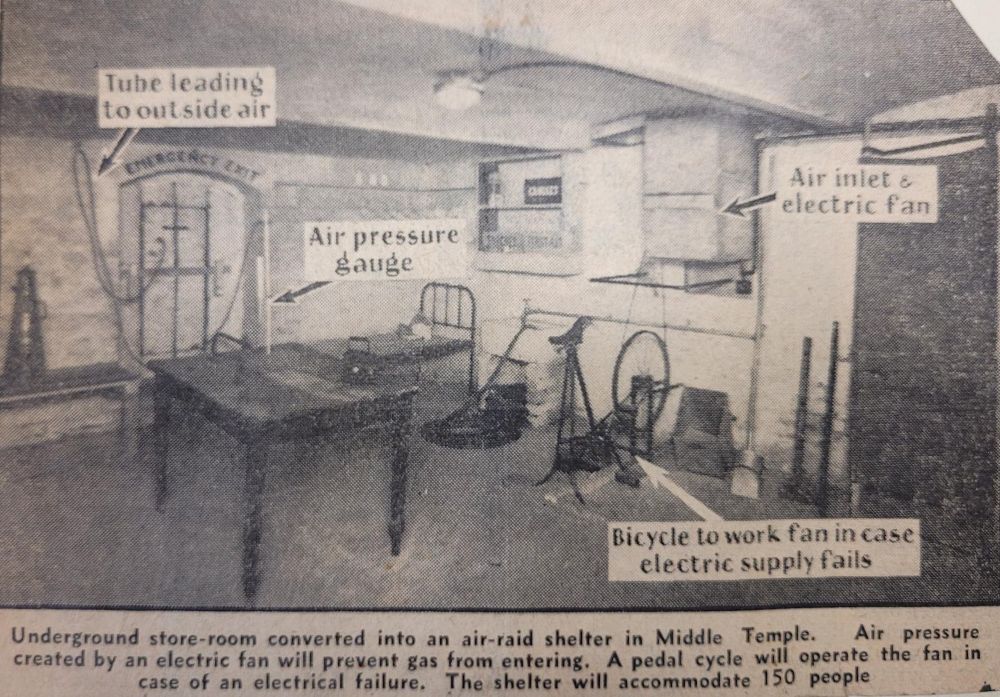

In the lead up to the Second World War, the Inns made practical preparations in anticipation of hostilities. Predicting future air raids, the Temple furnished itself with seven air raid shelters of varying capacities. All were below ground level, and these new den-like spaces became a temptation for the young choirboys of Temple Church to explore. In January 1939, the Under Treasurer wrote a furious letter to Dr. Ball, later named Thalben-Ball, the choirmaster at Temple Church, informing him that the Treasurer was ‘exceedingly annoyed to see the damage done as a result of the choirboys playing about in these shelters’ and asked Dr Ball to warn any rule breakers that he would recommend to the Choir Committee that they be dismissed for doing so in future. Unfortunately, the shelters did not remain a mere play area, and the choirboys would instead be huddling in the Goldsmiths’ Building shelter when the air raid sirens began to sound.

Newspaper clipping showing a Middle Temple air raid shelter, from News Chronicle, 4 July 1938 (MT/19/SCR/2)

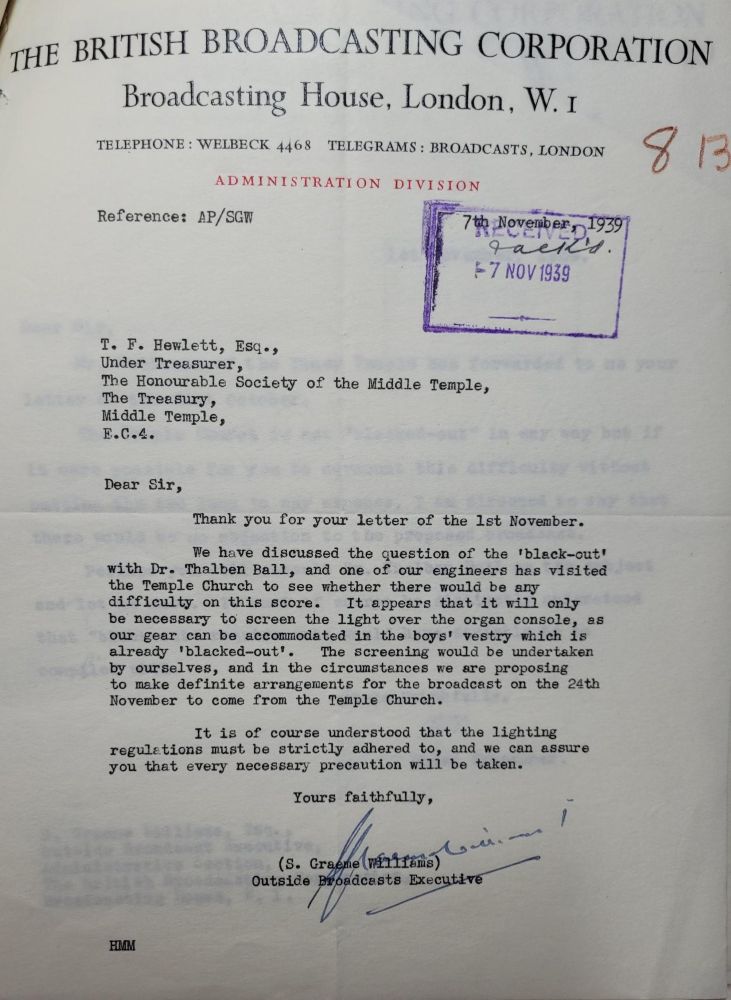

After the War began for Britain on 3 September 1939, blackout regulations were enforced across the Temple. The Church was no exception to these new prescriptions, and it was proposed that services be moved forward in the day to ensure that they did not overlap with the times that the blackout regulations were in force. Although avoiding using the church after dark was the easiest way to comply with the regulations, there were occasions on which other methods had to be used – for example, when the BBC requested that they be allowed to broadcast an organ recital to go out on the wireless between 10:45-11:15pm on 24 November 1939. The Under Treasurer wrote to the BBC informing them that ‘The Temple Church is not “blacked out” in any way’ but allowed that the recital could go ahead under the condition that ‘“black-out” requirements would have to be strictly complied with’. It was found that the light over the organ console was all that needed to be screened off, and the broadcasting equipment was housed in the boys’ vestry, which had already been blacked out along with the practice room.

Letter from the BBC to the Under Treasurer regarding blackout regulations during a broadcast from Temple Church, 7 November 1939 (MT/15/FIL/8)

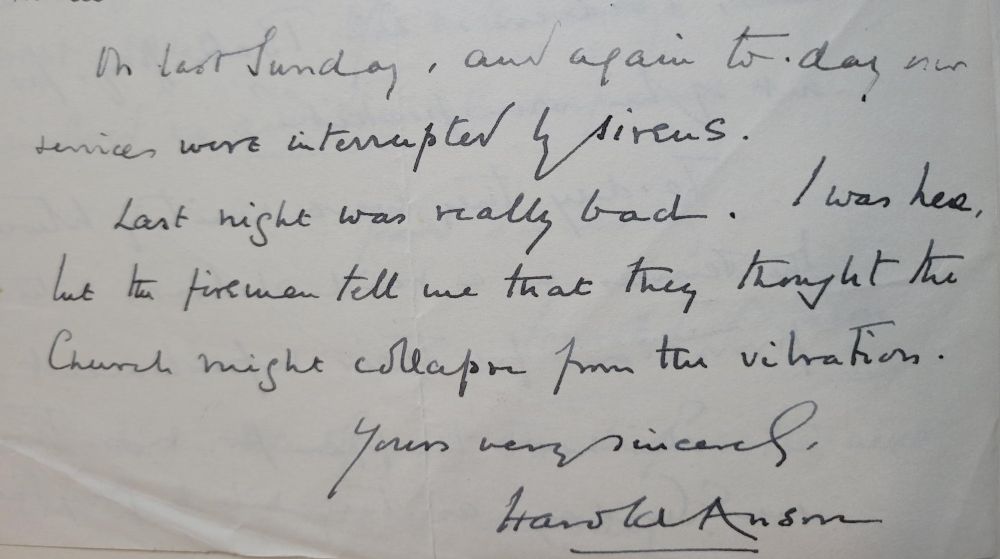

Throughout the first years of the war, services continued at Temple Church. The choirboys were evacuated with the City of London School to Marlborough College, though returned to sing in the church during the school holidays that year despite retreats to the air raid shelters sometimes being necessary. On 8 September 1940, Harold Anson, the Master of the Temple, wrote to the Under Treasurer regarding provision of the choirboys’ luncheons, commenting that ‘On last Sunday, and again today our services were interrupted by sirens. Last night was really bad. I was here but the firemen tell me that they thought the church might collapse from the vibration’. By 15 September 1940, after several interruptions to services that day, it was deemed that the situation at the Temple was getting too dangerous and services were discontinued until further notice. They resumed sporadically from 22 December until the Easter service in 1941 – the last service to be held before disaster struck Temple Church

Extract of a letter from the Master of the Temple to the Under Treasurer regarding the provision of choirboys’ luncheons, 8 September 1940 (MT/15/FIL/7)

Prior to May 1941, while worship had been disrupted, the Temple Church had experienced little physical impact from the air raids beyond some broken glass. This all changed with the disastrous raid of 10 May 1941. By the time that bombs started falling in Temple, Fleet Street and other areas were already ablaze. A bomb fell into the gardens, destroying the water mains – an incident, coinciding with the low tide of the Thames, that would prove disastrous to firefighting efforts in the Temple. An incendiary bomb landed on the roof of the chancel, which was quickly engulfed in flames, the water pressure too low to extinguish the blaze. Beecher Moore, a Senior Warden, provided a dramatic account of that terrible night, writing that ‘At two o’clock in the morning it was as light as day. Charred papers and embers were flying through the air, bombs and shrapnel all around. It was an awe-inspiring sight’’.

Photograph of the roof of Temple Church on fire, 10 May 1941 (MT/19/PHO/2/2/8)

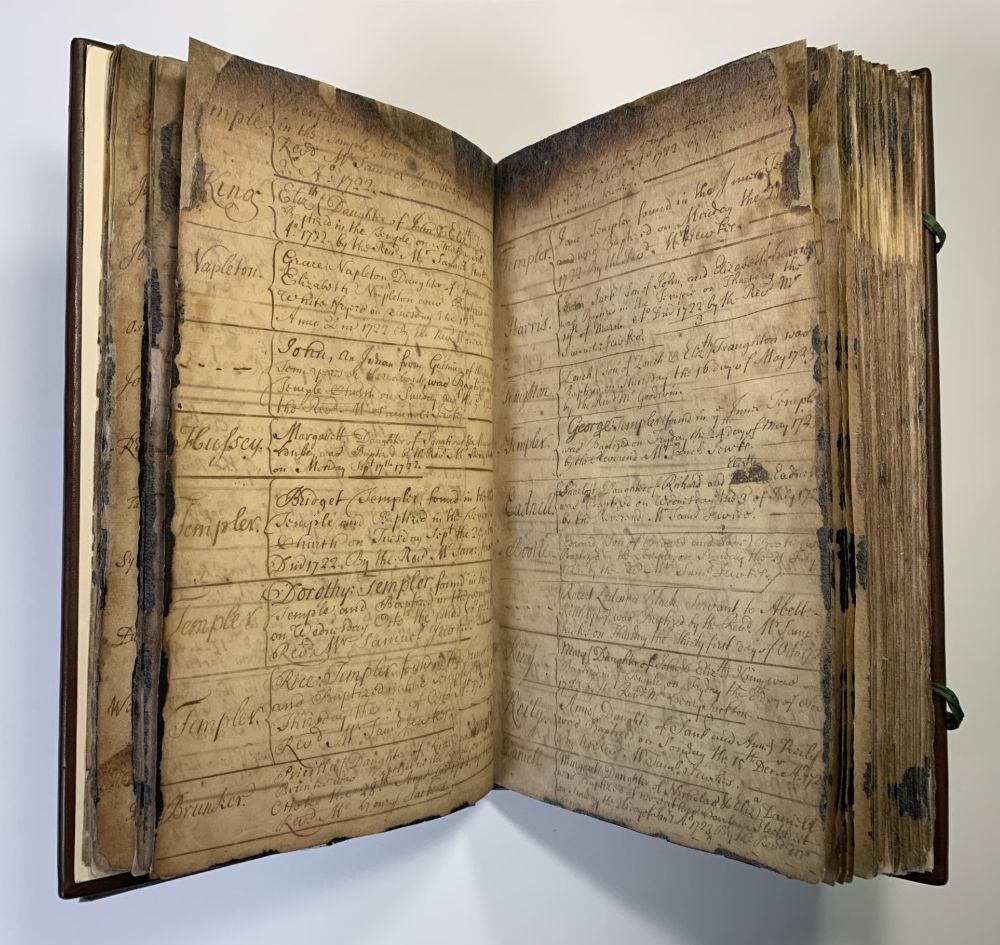

Beecher Moore recalled that the Wardens had a furious debate when they were informed that there was a safe full of gold plate in the Vestry about if it should be rescued and moved. Ultimately, they decided to leave it where it was, hoping it would withstand the intense heat of the fire, though Beecher Moore wrote that he was a little worried later in the evening on subsequent rounds when he saw molten lead pouring off the church and the vestry. Though he never learned the outcome of the Wardens’ decision that night, it appears to have been the right one as the safe was subsequently opened and the plate was found unharmed. The Church Registers were also found to have survived in the safe, though a bit singed around the edges by the intense heat coming from the fire. The registers were later conserved and now survive in the Middle Temple’s Archive, though still show evidence of their time in the blazing ruins of Temple Church.

Fire scorched pages of one of the Temple Church Registers, 1628-1704 (MT/15/REG/2)

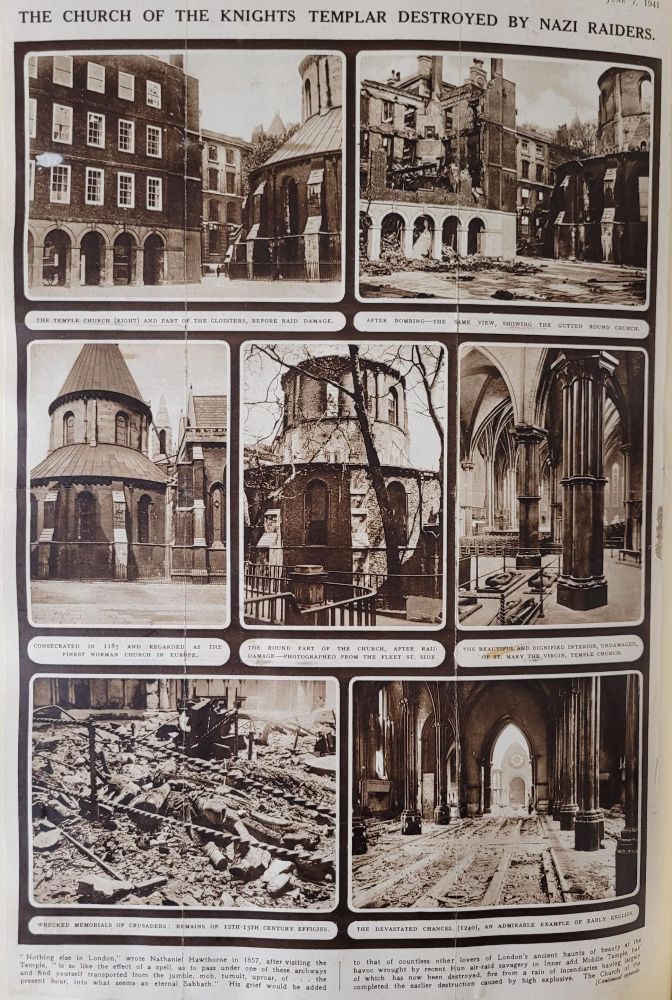

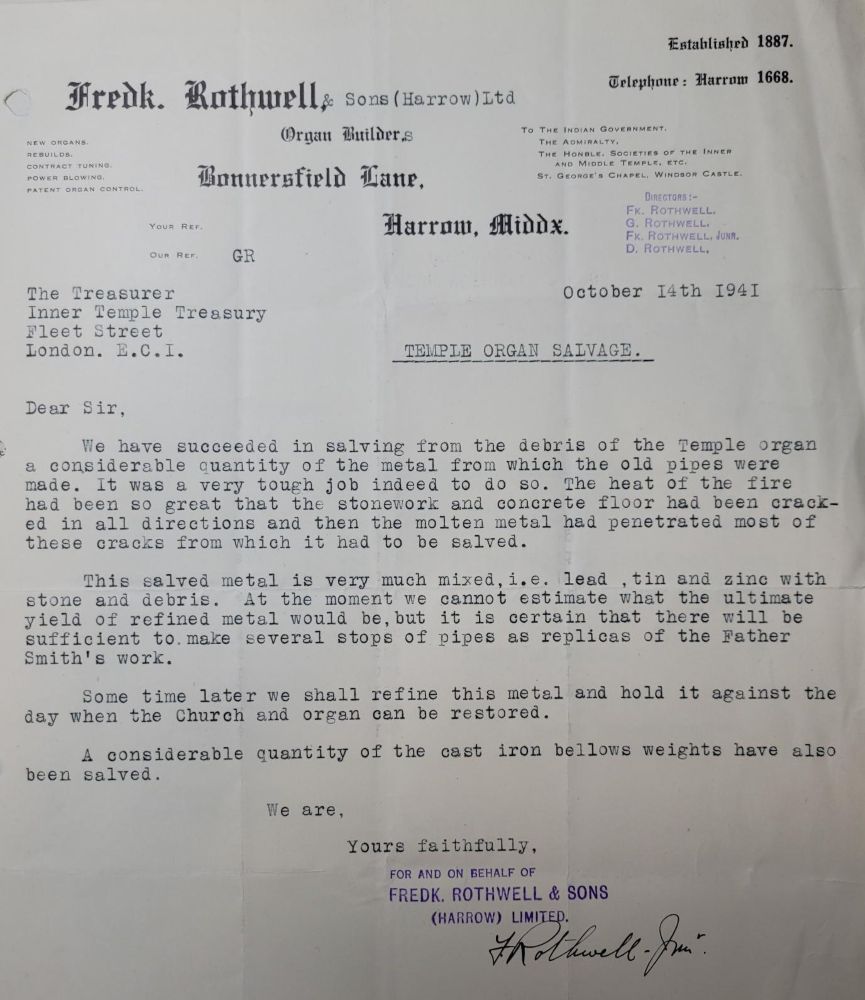

After the fires were put out six or seven hours after they first took hold, the damage to the church could be assessed. The roof of the Round was destroyed, having caved in on the effigies of the Templars – six of the eight of these were smashed and in an unrecognisable state. Many of the interior furnishings had been burned and the organ caught fire, the metal pipes being melted by the ferocious heat. The stained-glass windows were shattered and the heat of the fire cracked the chancel’s columns. Although the damage appeared to be overwhelming, there was some cause for hope – the walls of the church were intact, as were the oak doors and the roof of the choir. The devastation was severe, but unlike many of the buildings in the Temple, the church was not irretrievably lost.

Article illustrating the destruction of Temple Church from The Illustrated London News, 7 June 1941 (MT/19/SCR/2)

After the initial crisis was dealt with, work had to begin on weatherproofing the ruins of the church to prevent further damage by rain and frost, and to take the weight off weakened pillars. In June 1941, choristers began removing dust and debris from the church and in July cracks were observed in the stonework of the vaulting after rain poured in during a thunderstorm. The need for emergency construction work to stabilise the church and the surrounding buildings was evident, and Dove Brothers were brought in for this purpose. The main work they did in the church was in bricking in the effigies and the surviving monuments, the erection of temporary roofs, and the shoring up of the pillars. The Round remained open to the elements until 1943.

Letter from Frederick Rothwell & Sons regarding the salvage of metalwork from Temple Church’s destroyed organ, 14 October 1941 (MT/15/FIL/20)

After the fires had been extinguished, practical considerations relating to provision for the religious needs of the membership had to be worked out. It was apparent that a smouldering ruin was neither comfortable nor safe and so provision was made for Temple Church’s congregation to worship quarterly at St-Dunstan-in-the-West, which had suffered a lot less from the air raids. As a symbolic gesture, the silver altar cross of Temple Church, which had been presented by Master Finlay of Middle Temple, was sent to St Dunstan’s with the intention that it be used on the Alter as long as the Temple services were being held there.

Photograph of St Dunstan-in-the-West in the aftermath of an air raid, c.1940

Although normal services were discontinued in the ruined church, the Templars were determined to continue with carol services. In December 1941, over 100 Templars and friends met in the church unofficially, decorated with holly and lanterns, to keep the tradition going. This was continued the following year 20 December 1942 for the 100th Christmas time carol service, the Church determined to celebrate the centenary in their traditional home. The Christmas message of hope must have been a particularly poignant one in those years for the congregation as they sang amid the ruins of their beloved church.

Photograph of the ruined practice room and organ chamber of Temple Church, 1941 (MT/19/PHO/12/2/11)

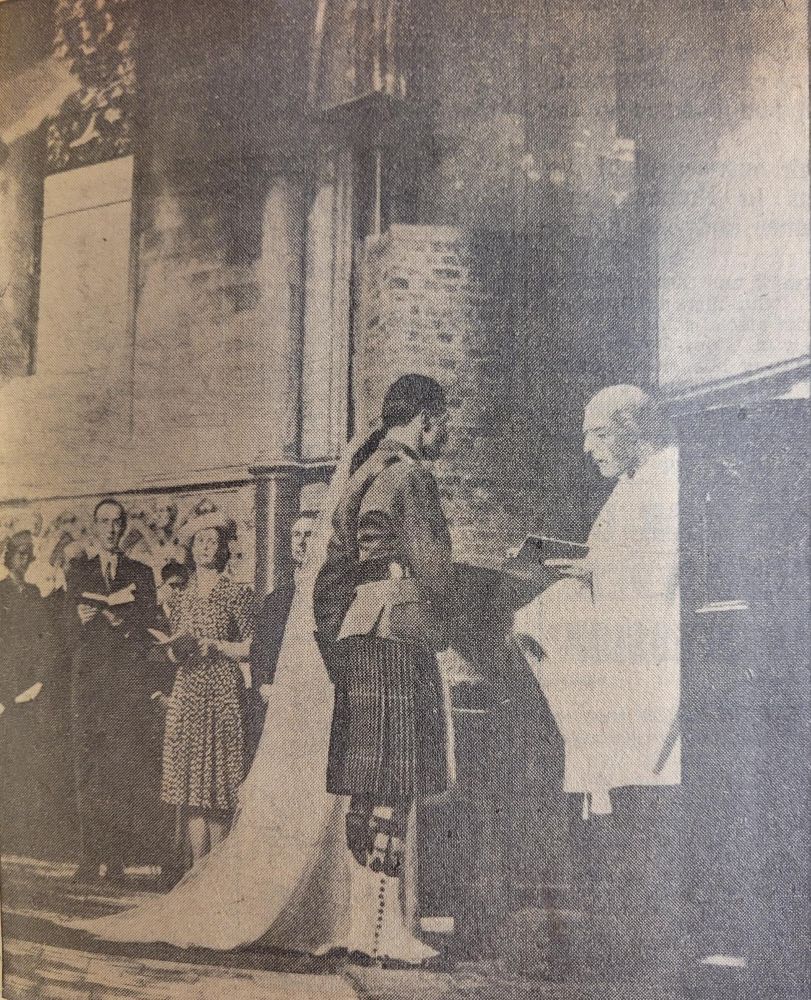

In 1943, the church was finally weatherproofed, and the following year temporary works were undertaken to make services possible once again. A carpet was laid from the west door, chairs and a small pulpit were installed, as well as a simple altar and working heating pipes. The first service to take place in this space, to the accompaniment of a grand piano, was the wedding of the daughter of Rowland Thomas, a Bencher of the Middle Temple, on 3 June 1944. The first full church service was held on 11 June and these continued monthly until March 1945 when the heating failed. The decision was then reluctantly taken to move services back to St-Dunstan-in-the-West until the church was restored.

Photograph of the wedding of Miss Elizabeth Thomas to Captain Dudley Richmond-Jones in the ruins of Temple Church, from the Sunday Express, 4 June 1944 (MT/19/SCR/2)

The events of the Second World War devastated Temple Church and left it a hollowed-out shell. Despite this, the spirit of the clergy and the congregation remained undefeated as they continued to worship in St Dunstan’s and occasionally in the ruined church itself. They resolutely preserved what remained of their church, despite the ongoing threat of further attacks, in hope of better times ahead when the church could be restored to the sense of magnificence it inspired before the War.

Photograph of the exterior of Temple Church with a roofless Round Nave, c.1941 (MT/19/PHO/12/2/12)