Over several centuries the population of London grew rapidly, culminating in a massive boom during the years of the industrial revolution. With this population increase, the provision of safe water supplies and waste disposal became of paramount importance in the prevention of disease. In the present day, mains water and efficient waste disposal are taken for granted, but the pre-industrial Middle Temple was forced to rely on much more primitive facilities. These not only made the Inn more susceptible to illness but also added an additional layer of inconvenience and unpleasantness to everyday life.

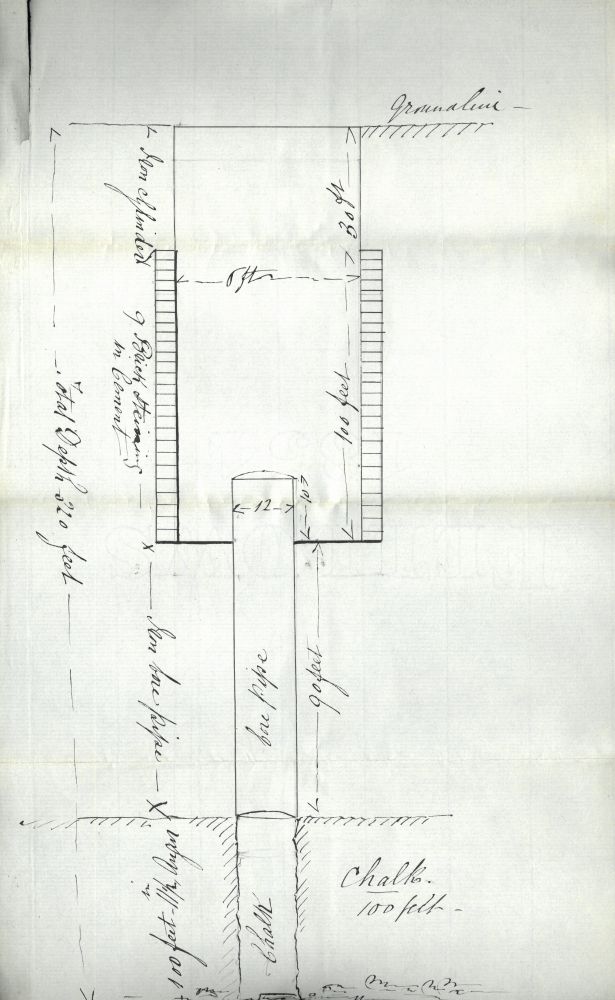

Sketch of a proposed bore for an Artesian Well at the Middle Temple, 1856 (MT/21/1/22/16/23)

In the medieval period, though the population of London was smaller, incidents of waterborne diseases such as dysentery, typhoid and cholera were common. While the urban poor may have resorted to drinking directly from the River Thames, the water was known to be unwholesome. It is likely to have been so at the Middle Temple, which lay outside and upriver of the City of London, but downstream of the City of Westminster, and residents of the Inn would probably have avoided drinking from the river when possible. It is likely that the Inn would have made use of wells, primitive hand pumps and water carriers, though documentary evidence is lacking during this period. By the seventeenth century, water was available from several different sources, with one giving the name to ‘Pump Court’, shown on Ogilby and Morgan’s 1677 map of London.

Photograph of Pump Court with the water pump visible on the left of the image, 1896 (MT/19/SLI/104)

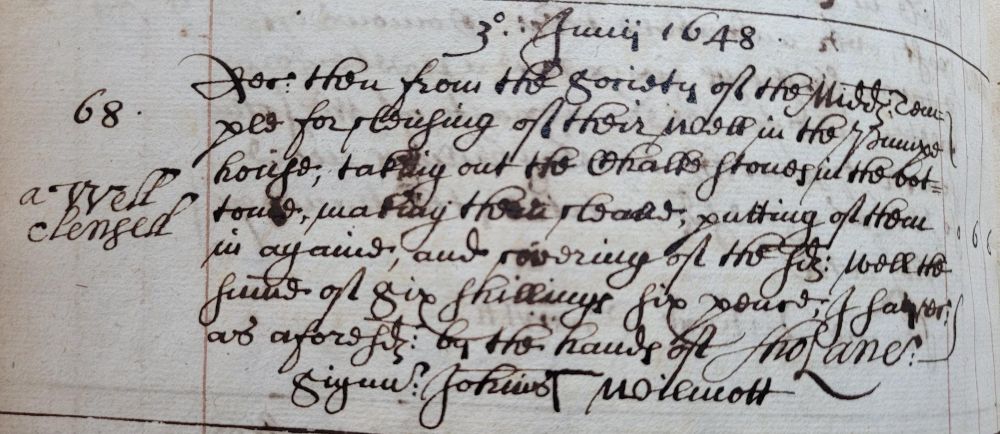

Records from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries record the location of several of the Inn’s other water sources – in Middle Temple Lane, the ‘Pump House’, the garden and the cellar of the Hall. Some of these may have drawn on old wells or aquifers. This appears to have been the case in the old Pump House as a 1648 receipt records that it drew on a well. 6s. 6d. was paid ‘for cleansing of their well in the Pump House, taking out the chalk stones in the bottom, making these clean, putting them in again, and covering of the said well’. These chalk stones, with their intentional inclusion in the well, may have been used to aid filtration of the water or to help stabilise the bottom.

Receipt for the cleaning of a well, 3 June 1648 (MT/2/TRB/6)

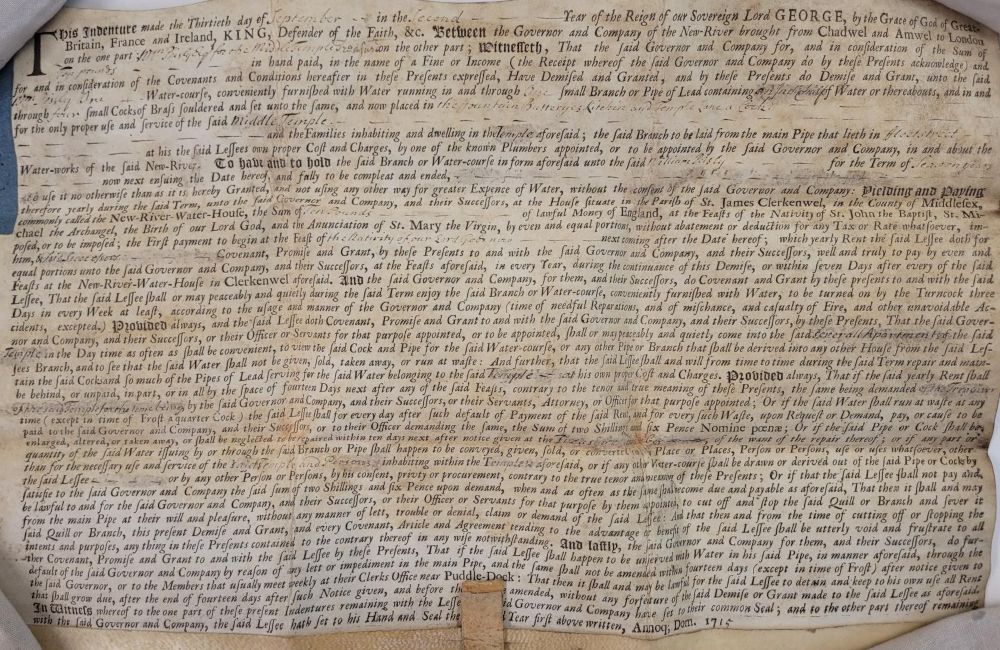

Some of the Inn’s pumps were supplied with water by the New River Company, a company founded in 1619 to supply clean drinking water to London from springs near Ware in Hertfordshire and the River Lea. With the increase in London’s population, the water that the wells and water carriers supplied became polluted through the cross-contamination of cess pits into the groundwater and this private company aimed to remedy that by bringing fresh water to the city through wooden pipes made of elm. The first record of the Inn’s patronage of the New River Company is a receipt dated to 1653. The precise nature of supply was not recorded at this time, but by 1700, New River Company water was being used to supply the fountain, kitchen, cellar (possibly for the use of the buttery) and, based on later receipts, likely the pump in Middle Temple Lane. A more formal ‘lease of a watercourse’, dating to 1715, allowed Middle Temple the use of one lead pipe laid from the main branch of the city’s water supply in Fleet Street.

Lease for a watercourse between the New River Company and the Middle Temple, 30 September 1715 (MT/4/1/2/5/6)

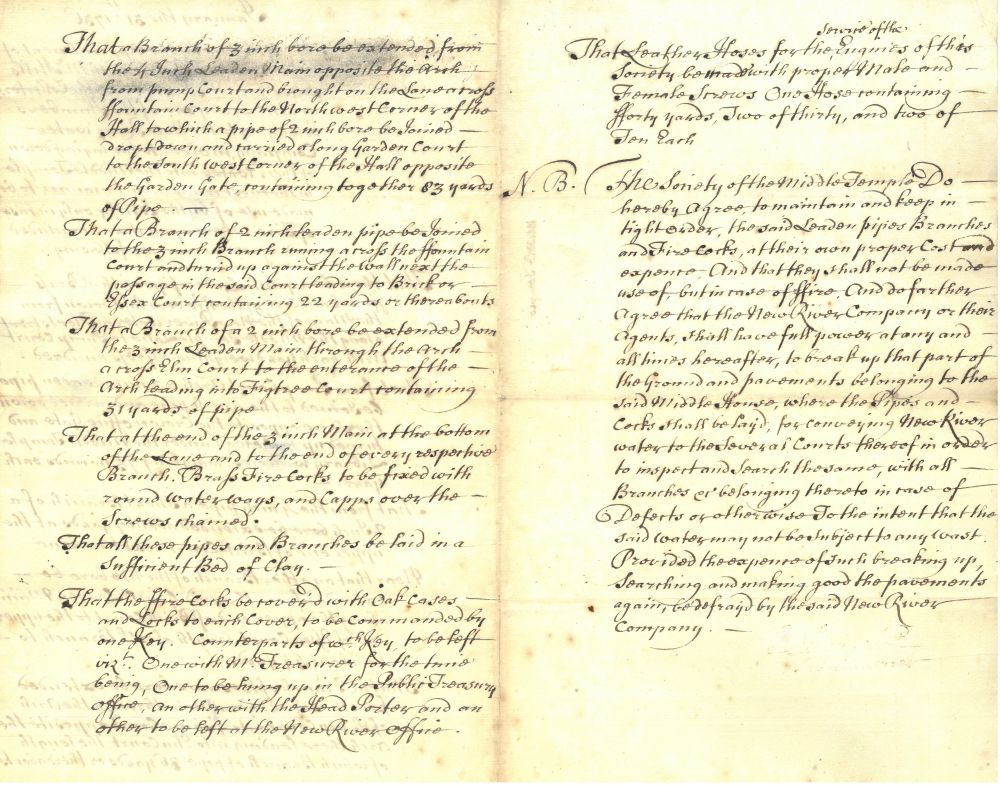

In 1737, the Middle Temple expanded their use of the New River Company by contracting them for the laying down and supply of a fire suppression system that was to be made use of by the Society only in case of fire. This involved the installation of an extensive network of lead pipes, consisting of seven separate branches, that were laid throughout the courts of the Society, and brass fire cocks were fitted to the end of each branch. These were enclosed with wooden boxes and locked to prevent misuse of the water supply. In the event of a fire, these would be unlocked and hoses of the Inn’s fire engine attached to supply the water for firefighting.

Agreement between the Middle Temple and the New River Company for the supply of water for the exclusive use of fire suppression, 31 January 1737 (MT/6/RBW/57)

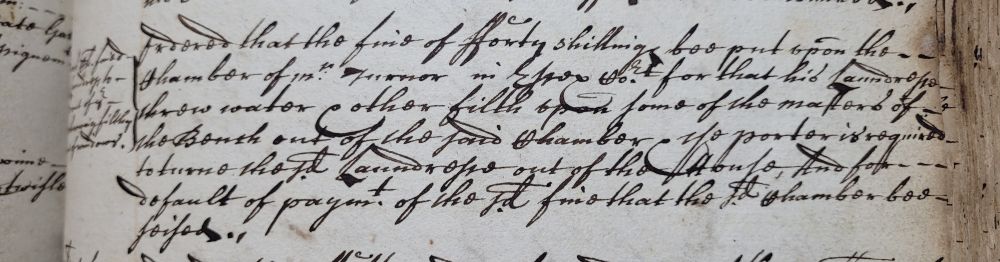

While the supply of fresh water was significantly advancing, the disposal of wastewater and sewage continued to present difficulties for the Inn. Lack of convenient access to waste disposal facilities encouraged laziness amongst the residents and the laundresses who cleaned their chambers, with refuse being thrown out of windows and left in cellars, courts and gutters. Frequent orders were passed to combat the accumulation of filth, usually threatening offenders with fines and the confiscation of chambers. This suggests that this recurrent problem was causing widespread distress to the community, especially in cases where the waste struck passersby. One such case occurred in 1689, when Mr Turnor of Essex Court was issued a fine of 40s. by the Inn’s Parliament ‘because his laundress threw water and other filth on some of the Masters of the Bench out of the chamber’. In addition to the fine, the careless laundress was thrown out of the Inn, depriving her of employment.

Order of Parliament for a fine to be issued to Mr Turnor due to his laundress throwing water and filth on Masters of the Bench from his chamber window, 14 June 1689 (MT/1/MPA/6)

Until the construction of London’s sewer system in the nineteenth century, the city was served by open or partially covered drainage channels that ran alongside streets and public spaces. It is unclear whether the Inn’s drains and sewers were covered, but there is evidence that they ran directly into the Thames. This includes references in 1767, ahead of the 1770 embankment of the Thames, to sewers and drains running through the Inn’s wharf wall. These drains serviced not only various chambers of the Inn, but communal toilets known as ‘bog’ or ‘necessary’ houses, and shops and taverns on Fleet Street. In 1767, after the construction of new ‘necessary houses’ in the garden, soil flowing into the river was found not to be carried away by the ride as expected. The smell became so odious that the Inn’s unfortunate Gardener and Under Porter were ordered to go down to the river and clean the soil. They later petitioned the Inn’s Parliament, stating that ‘the office is so very disagreeable and troublesome they are not able to perform it and praying to be discharged from it’. Fortunately, the mason and bricklayer who constructed the building undertook to pay to keep the area clean, saving the Inn’s employees this unsavoury task.

Ground plan of a landing place proposed by watermen with drain water flowing into the Thames from either side of Temple Stairs, c.1772 (Plan/3/A/6)

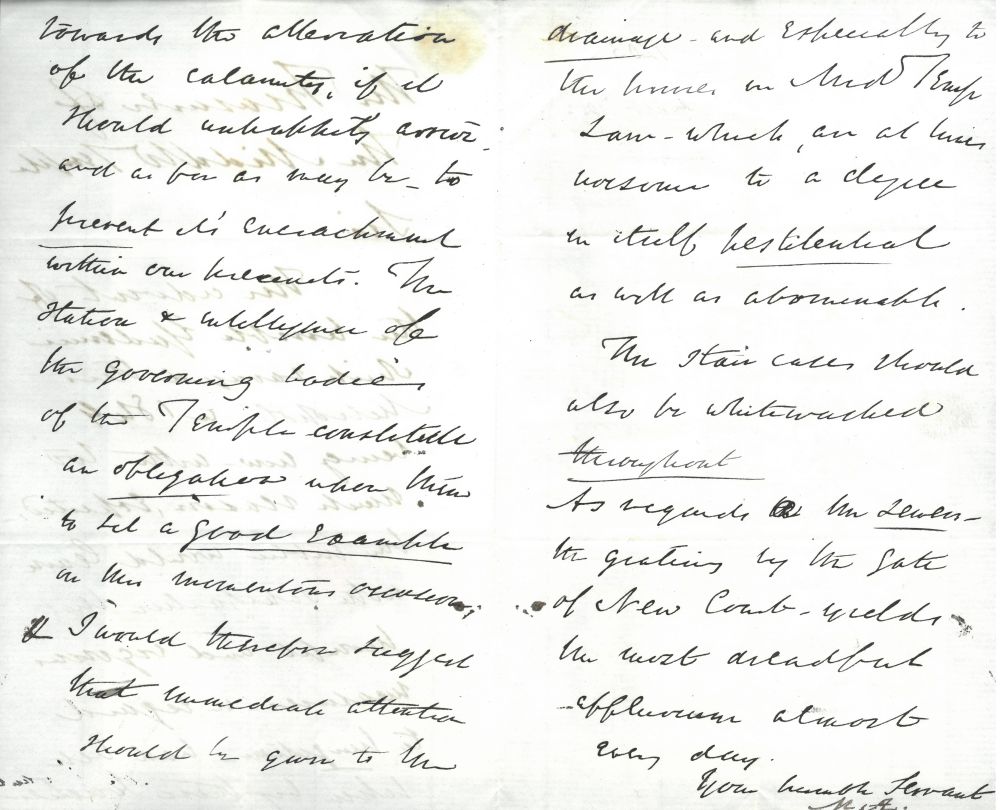

The barely adequate sanitation facilities at the Inn became completely inadequate in the face of the mid-nineteenth century population explosion in London. Not only was the ground water being contaminated by high volumes of waste in the cess pits, but mains drinking water was being pumped into the city downstream of sewage outlets, causing devastating outbreaks of cholera. A letter written to the Treasurer from ‘M.A.’ in 1852 referenced the cholera outbreak of 1849 and begged that the Inn take measures ‘towards the alteration of the calamity’. Particularly, he wished for attention to be paid to the drainage in Middle Temple Lane, ‘which is at time noisome to a degree in itself pestilential’, that staircases be whitewashed, and ‘as regards the sewer – the grating by the gate of New Court yields the most dreadful effluence almost every day’ – this must have been particularly frightening to residents as the prevailing theory at the time was that disease was caused by bad air or ‘miasma’, identifiable by bad smells. Unfortunately, M.A.’s fears were realised in 1853, when another cholera outbreak ravaged the city.

Letter from ‘M.A.’ regarding sanitation measures the Middle Temple could implement to prevent an outbreak of cholera, 1 September 1851 (MT/1/PPA/2404b)

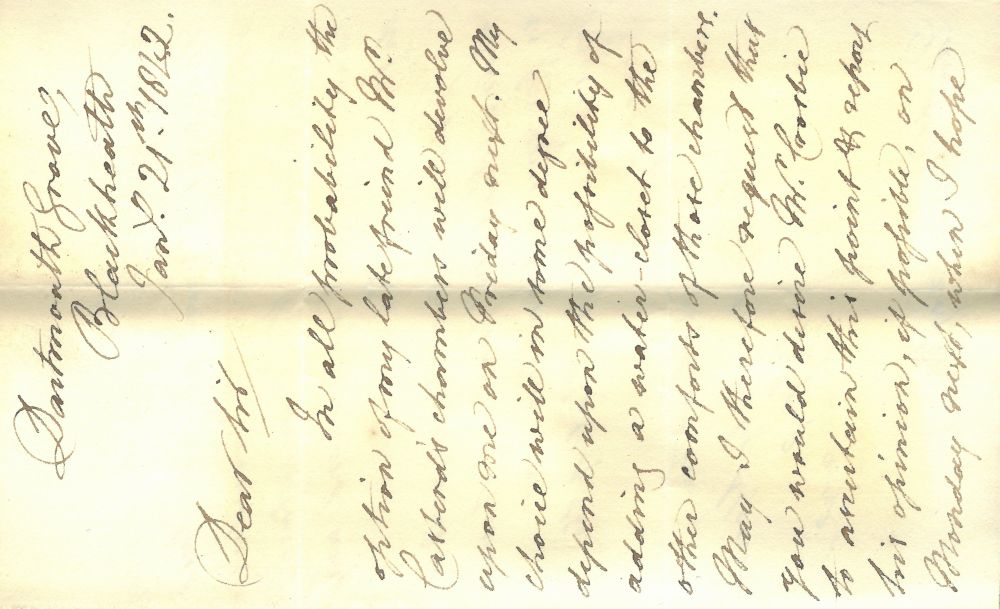

By the 1830s, the Inn’s traditional ‘bog houses’, which usually made use of cess pits, in some cases connecting to drains, started to be converted into flushing water closets. Throughout the next few decades, more and more petitions were submitted to the Inn’s Parliament requesting the installation of this convenience in chambers, with the pace dramatically accelerating in the 1850s. With the installation of water closets also came the introduction of plumbed-in sinks, a luxury that had been confined to the kitchen and the buttery in previous centuries. The combination of these two amenities served to dramatically increase comfort and hygiene in chambers.

Letter from H. Legge stating that the choice of him taking on his late friend’s chamber depended on a water closet being added, 21 January 1842 (MT/1/LIN)

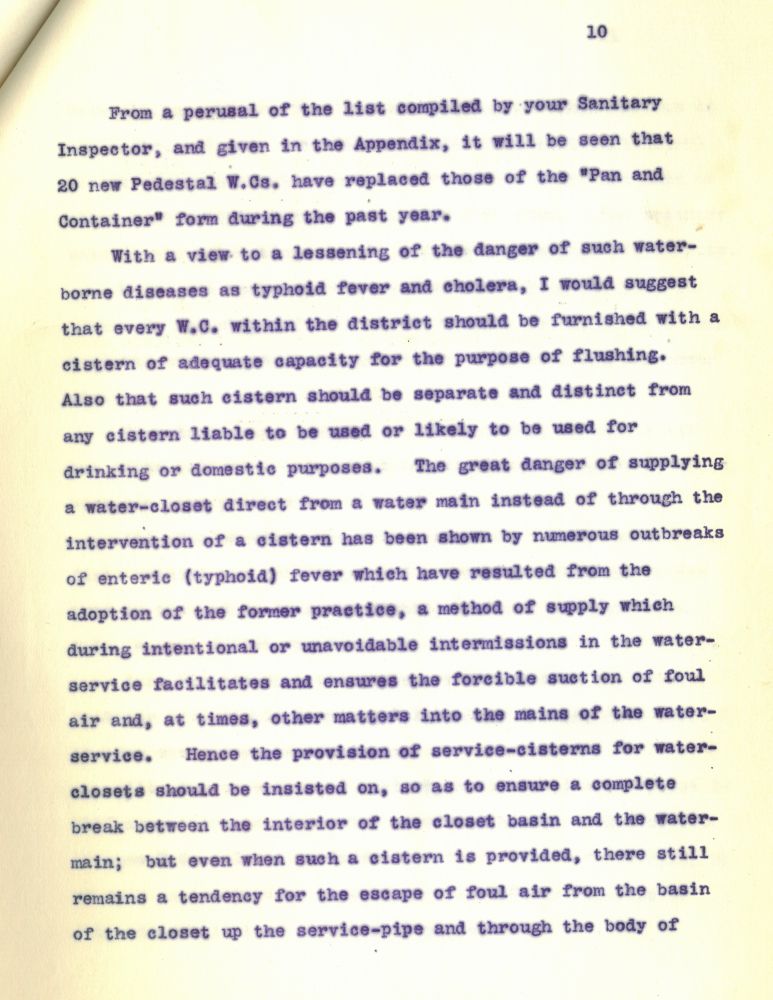

From 1894 to 1953, annual reports were produced by the Middle Temple and Inner Temple’s Medical Officer of Health, which covered vital and mortal statistics, notification of infectious diseases, water supply and reports on sanitary work carried out during the year. When the reports began in 1894, most of the water in the Temple was supplied by the New River Company, but some cisterns or wells were still in use and were noted to be badly placed – some directly over or in close proximity to the water closets, allowing for possible contamination. It was recommended that these cisterns be phased out for anything other than flushing the water closets. By the 1904 report, all water supply is noted as coming from the mains, the same year coincidentally that the New River Company transferred to the Metropolitan Water Board, which was subsequently transferred to the Thames Water Authority, later Thames Water, in 1974.

Extract from a report from the Middle Temple and the Inner Temple’s Medical Officer of Health regarding the Inn’s water supply, 1894 (MT/1/MOH/1)

For those living in modern Britain, it can be difficult to imagine a world without the conveniences of piped water and a functional sewer system. However, these were luxuries to previous generations of Middle Templars, who experienced difficulties in accessing clean, safe drinking water, and endured a living and working environment characterised by dirty and smelly streets and courts. Illnesses such as cholera, diphtheria and typhoid were never far away and it is only through the installation of modern utilities from the mid-nineteenth century onwards that the clean, safe environment of today was created.