This January, the Inn embarked on a project to inspect, survey and clean its iconic double hammerbeam roof. Completed around 1573 during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, it is a remarkable remnant of a medieval architectural style and is noted for being one of the finest surviving of its type.

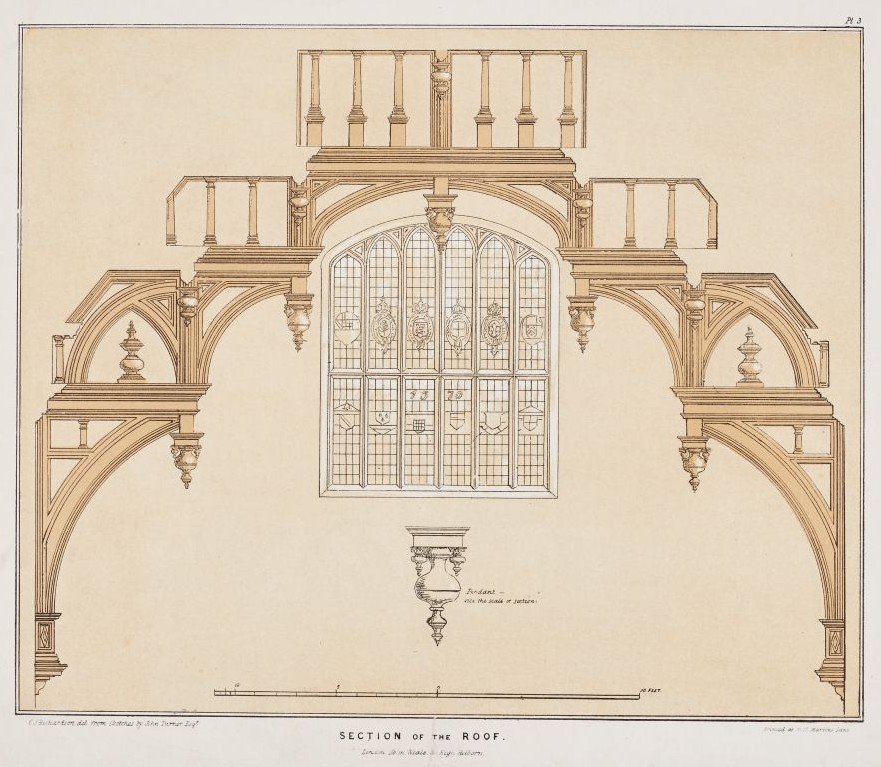

Section of the roof of Middle Temple Hall, c.1844 (MT/19/ILL/D/D5/3)

The earliest known hammerbeam roof was built around 1300 and took the form of a single hammerbeam construction. The design meant that the width of halls could be made greater than 20ft (6m) without encumbering the floor space with support posts, creating a larger communal area, and transferred the outward force of the roof down the wall providing stability and strength. It is estimated that there are only about 200 single hammerbeam roofs and 30 double hammerbeam roofs left in England, and these are overwhelmingly concentrated in the east of the country. The survival of the roof of Middle Temple Hall is due in part to its continued use as the communal hub of the Inn and the care that the Society has taken in preserving the timber structure for 450 years.

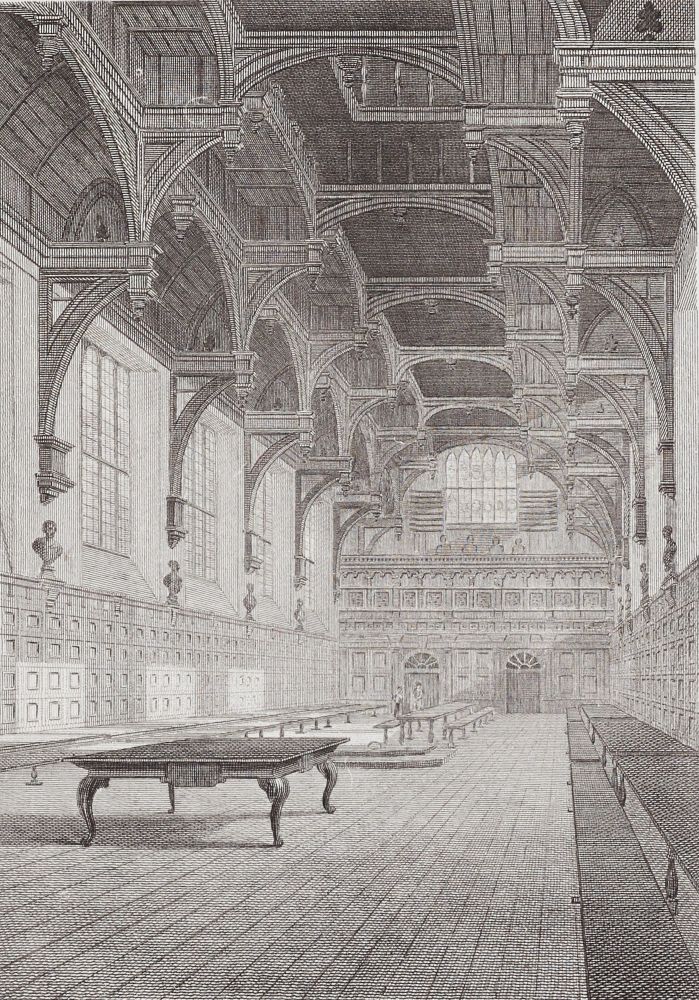

Print of the interior of Middle Temple Hall, 15 May 1804 (MT/19/ILL/D/D2/0)

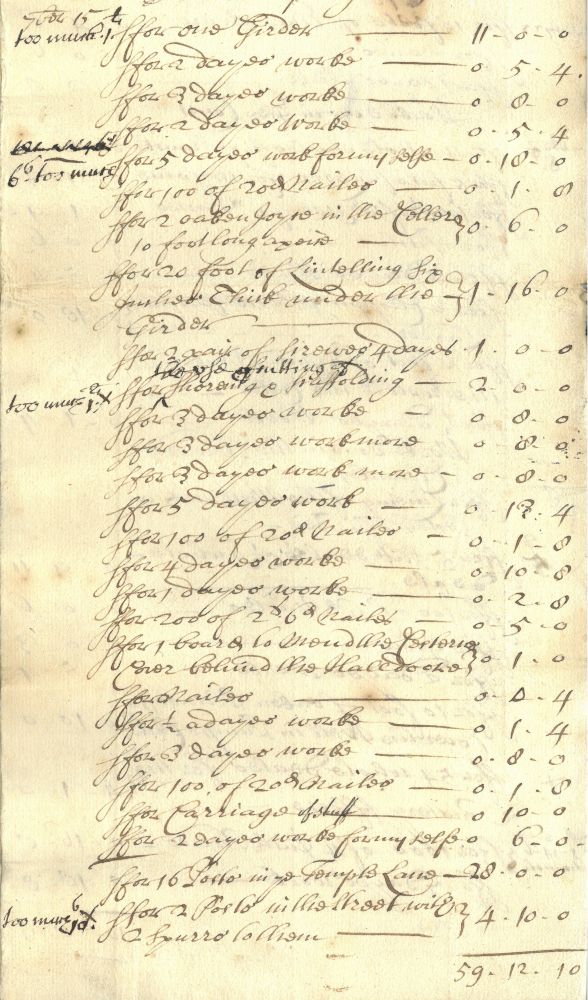

Even in the century directly after its construction, the roof of the Hall was in need of repairs. In the year 1658-1659 the roof was tiled and the Treasurer’s receipt book for 1670 states that at this time the Inn was ‘Making good ye decay at ye upper end of ye Hall and new working upon some parts of ye Bay Window at the end of ye Hall and scaffolding and securing 3 pendants in ye Hall to keepe ye roofe from dying further out’. Further repairs in 1673 and 1674 were unsuccessful and in 1676 it was decided that substantial works should be completed at the south bay window and the south-west corner of the Hall. Further repairs to both sides were completed and a ‘new-girder’ was put in place during 1693.

Carpenter’s bill for repair work to the Hall, 1693 (MT/2/TAP/20)

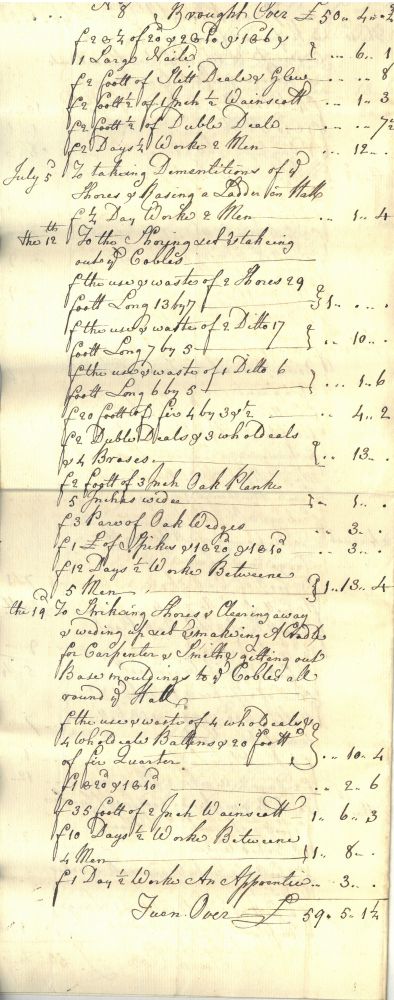

In 1698 workmen were also employed in ‘new ripping and repairing the Hall throughout’. A new lantern was constructed in 1732, and further renovations were completed on the roof in 1755. While detailed archival research into repairs over the following 150 years is yet to be undertaken, a roll of lead inscribed with a man’s name and the year ‘1853’ indicated that lead flashing was replaced at least once in that century.

Carpenter’s bill for repair work to the Hall, 1755 (MT/2/TAP/83)

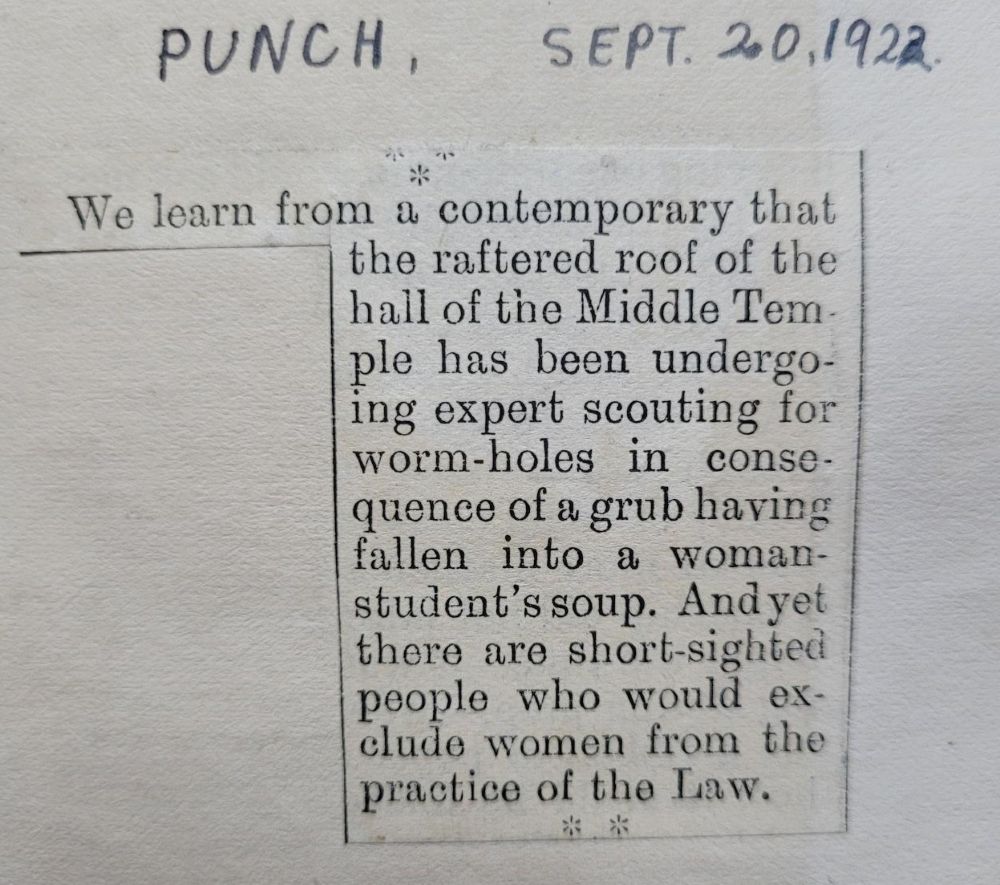

Some limited works on the roof were completed in 1907, but by 1922 its condition was causing great concern. In the satirical Punch magazine it was reported that ‘expert scouting for worm-holes’ was in progress due to ‘a grub having fallen into a woman student’s soup’. While the accuracy of this anecdote is unknown, something must have alerted the Benchers to possible structural problems in the roof as they commissioned a report from Sir Frank Baines of the Board of Works. He found that almost all of the timbers through the section he examined had been attacked by deathwatch beetle, but was ‘only serious in certain instances’. One north side wall post had been ‘hollowed out to a mere shell’ and there were very decayed timbers supporting the lantern on the south side. Baines suggested that every timber in the Hall should be sprayed with insecticide, and though a few of the most damaged timbers would need complete renewal, he suggested that there was no need for a complete scheme of strengthening as had been required for other Tudor roofs.

Article from Punch regarding blackwatch beetle in Middle Temple Hall, 20 September 1922 (MT/19/SCR/1)

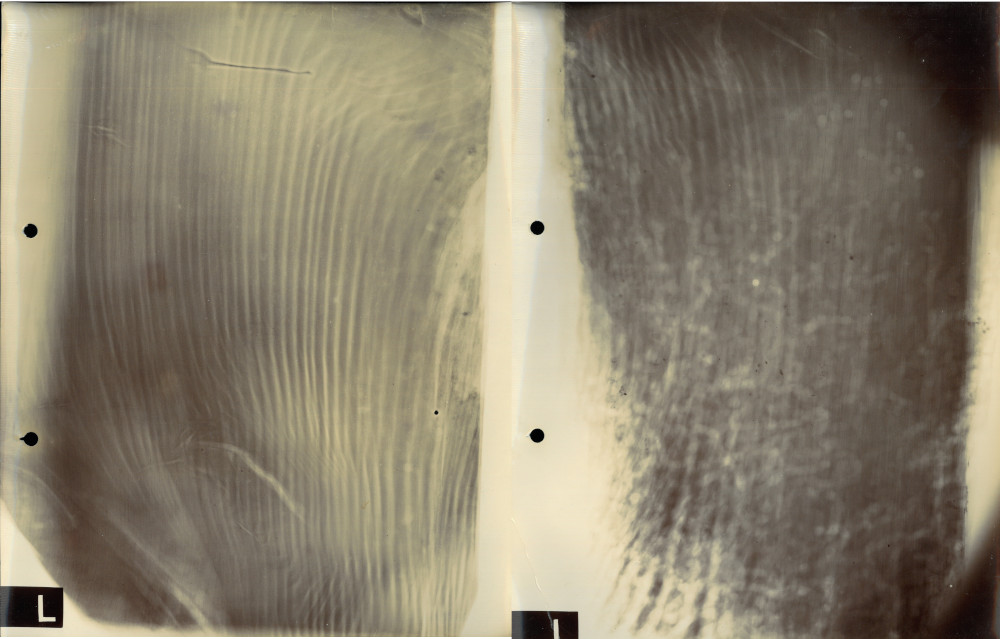

The Benchers decided that it would ‘not be advisable to seek assistance of a Government Department for dealing with the roof of the Hall’ and that it was more appropriate to instruct the eminent architect Sir Aston Webb to carry out the work. Webb, who had in 1912 designed the Benchers’ entrance on Middle Temple Lane, inspected the roof on 23 July 1923 and found that many of the roof timbers were very decayed, principally due to attacks by the aforementioned deathwatch beetle. X-Rays of the roof timber included in Webb’s report show the difference between an end with no infestation and a badly infested end of timber – one reassuringly solid, the other riddled with invisible burrow systems. This beetle causes this damage by laying its eggs in the timber, and the larvae, also known as woodworm, then feast on the interior of the wood. They live inside the timber, creating boreholes inside, for up to ten years before emerging, meaning that an infestation can invisibly be causing damage long before its discovery. Much of the destruction they cause cannot be seen from the outside of the timber, even as they gradually erode its structural integrity.

X-Rays of beams attacked by deathwatch beetle. A ‘sound end’ of the timbers (left) and an ‘attacked end’ of the timbers (right), 1923 (MT/6/RBW/226)

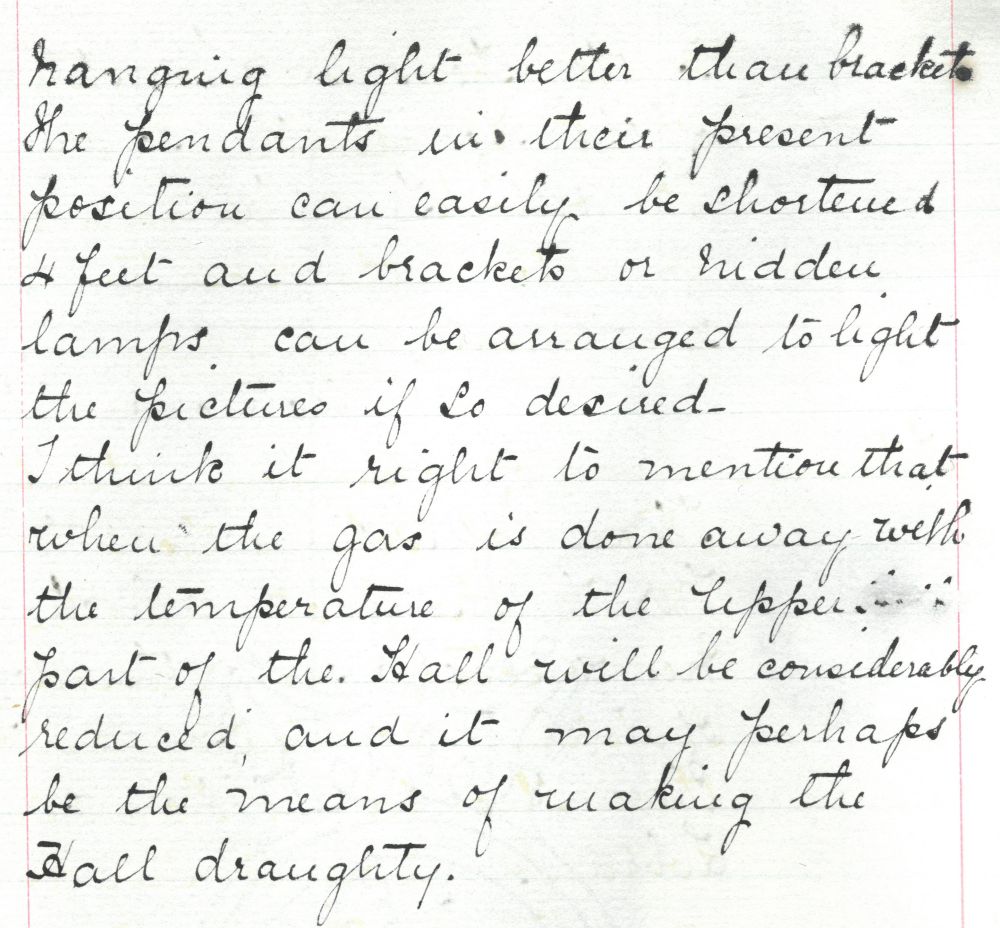

Around the same period the timbers of the roofs of Westminster Hall and Hampton Court Great Hall were found to be similarly attacked by the beetle, though Middle Temple Hall was in a much better condition than these buildings. It was theorised that the Hall’s near constant-use as a communal space throughout the centuries had helped to preserve the timber. The medieval-style open hearth that had been used to heat the Hall until the nineteenth century had produced enough fumes, smoke and heat to discourage pests, a function continued by the large gas chandeliers which had been introduced later. These chandeliers had been replaced by electric lighting in 1894, from which point the protection afforded by heat and fumes no longer existed.

Paper produced prior to the installation of the electric light referring to decreased levels of heat at the top of the Hall, 1894 (MT/6/RBW/206)

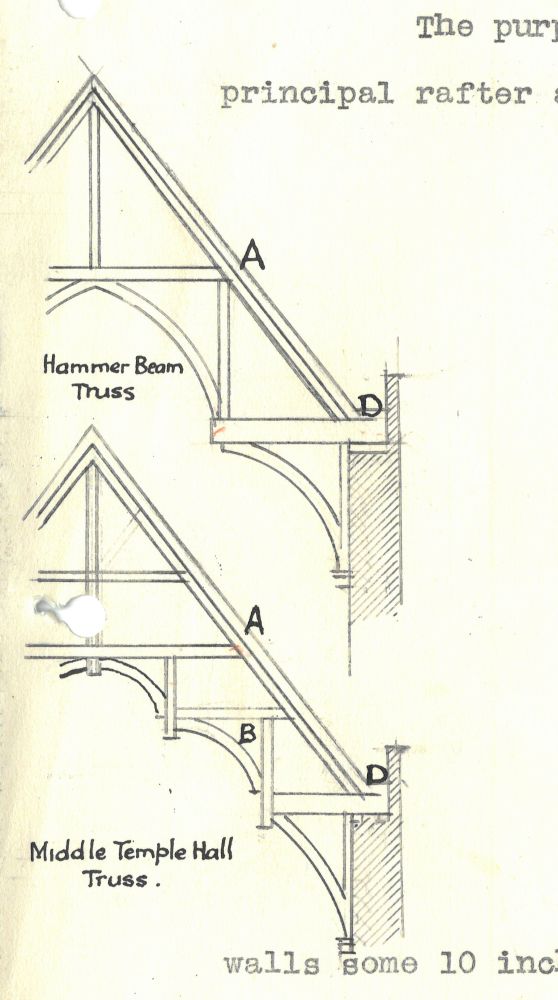

As well as the beetle infestation, Sir Aston Webb identified a flaw in the original construction of the Hall roof during his inspection. The purpose of a hammer beam truss was to give support to the main roof rafters at their weakest point in the centre (point A in Webb’s original diagram). This was achieved through the placement of a vertical collar beam at the weakest point, rested on a horizontal beam and supported by a curved brace, carrying the weight of a roof down the wall. In the case of our roof, this crucial vertical beam did not meet the roof at its weakest point and overshot the horizontal beam, rendering the whole hammer beam support useless. The main roof rafters had therefore to support the whole weight of the roof, and by 1923 were sagging up to 4 inches at their weakest point and being pushed out by 10 inches by the added horizontal force at the top of the walls. Some attempts had been made to remedy this issue during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but the inspection found that some of these main rafters had in fact cracked through due to the stresses that they had been placed under for three and a half centuries.

Diagram of a standard hammer beam roof and the flawed construction of the Middle Temple roof, 1923 (MT/6/RBW/226)

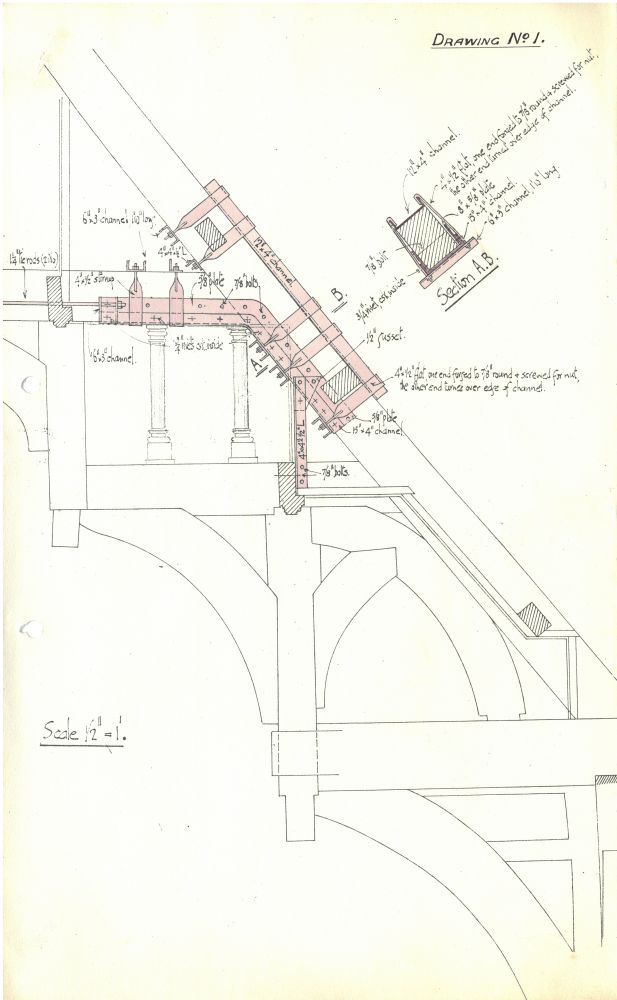

In order to remedy the various issues found in Webb’s report, the Hall was closed for a period of over four months while work was carried out. The beams were treated with insecticide and extensive ironwork, in the form of steel plates and fastenings, were added to strengthen the beams. Several hazardous timbers were removed and the lantern, which was in an unsafe condition, underwent extensive repairs.

Drawing of repairs to the roof of Middle Temple Hall proposed by Sir Aston Webb, 1923 (MT/6/RBW/226)

The greatest threat to the survival of the Hall in its history came during the Second World War when it came close to destruction. The east end was blown apart on 15 October 1940 and in March 1944 the roof was set ablaze. It was only through the valiant efforts of the firefighters, many of them staff of the Inn, that the roof was saved. By the time the last fires were extinguished, the whole lantern was completely destroyed, and many timbers were burned almost the whole way through. It was thought at one point that complete rebuilding would be required, but fortunately the roof remained stable and repairs began in 1946, funded with generous contributions the American Bar Association and Canadian Bar Association. These were completed and the Hall was formally reopened in 1949 by HM Queen Elizabeth, later the Queen Mother.

Photograph of the burning roof of Middle Temple Hall, March 1944 (MT/19/PHO/4/1/7)

Since the post-war restoration of the Hall roof, the Inn has remained vigilant about its condition, looking for evidence of movement or resurgence of the deathwatch beetle, with inspections being carried out roughly once every ten years. The current 2026 works are a continuation of the Inn’s commitment to the preservation of its much-loved Hall, both honouring its past members and caring for it in stewardship for the continued benefit and enjoyment of generations of Middle Temple members yet to come.

Photograph of the roof timbers taken during inspection and repairs, 1964 (MT/6/RBW/325)