In 1642, long-standing tensions between King Charles I and his Parliament erupted into a Civil War that tore England apart and killed a higher proportion of the population than World War One. The divisions that caused the war were both political and religious. Charles believed in the Divine Right of Kings and that he should rule without interference. He had ruled without recourse to Parliament between 1629 and1640 and during these eleven years of ‘Personal Rule’ had sown the seeds of religious conflict by favouring High Anglicanism over Puritanism. This shared many features with Catholicism and led to fears that the Roman Catholic Church was being covertly re-introduced back into England. Charles I had compounded these fears by marrying a Catholic wife in 1625, Queen Henrietta Maria, against the advice of Parliament. In 1640, the King was forced to recall Parliament in order to raise funds to supress rebellion in Scotland caused by his religious reforms. Parliament deviated from the King’s agenda and started to push through their own reforms to limit his authority. The conflict escalated in January 1642 when the King tried and failed to have five Members of Parliament arrested for treason – five days later he fled London for the north and raised his standard at Nottingham on 22 August.

Portrait of King Charles I by Sir Peter Lely, c.1625-c.1680

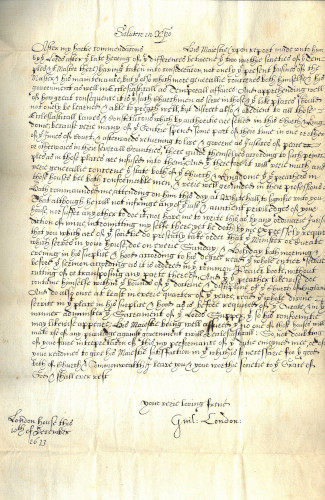

During the Personal Rule, Temple Church was affected by the religious reforms that contributed to the war. In 1633 the controversial William Laud, Bishop of London and later Archbishop of Canterbury, wrote to the Benchers of the Middle Temple and Inner Temple to communicate the wishes of the King regarding religious practice, stating that not only should the churchmen of Temple Church be learned and able to preach well, but ‘discrete also and obedient to all those ecclesiastical laws and constitutions which by authority are settled in this Church and Kingdom, because very many of the gentry spend some part of their time in one or other of the Inns of Court, and afterwards returning to live and govern as Justices of Peace or otherwise in their several countries, there guide themselves according to such principles as in those places are infused into them’. His order required that the minister or curate should wear surplice and hood ‘according to his degree’ when conducting services, and were to conduct the service according to the Common Prayer Book before the sermon, without cutting or transposing any part, and that the preacher ‘contain himself within the bounds of the doctrine and discipline of the Church of England’.

Letter from William Laud, Bishop of London, to the Benchers and members of the Middle Temple and Inner Temple, 1633 (MT/15/TAM/67)

There is no direct reference to the outbreak of conflict in the Middle Temple’s Minutes of Parliament, but it is evident from surviving financial records that the Society was preparing for the possibility of war. Around February 1642, the Inn purchased seventeen pounds of gunpowder, two and a quarter pounds of match and sixty pound weight of bullets, probably intended for use with the Inn’s eighteen old muskets, which were moved to the Lower Parliament Chamber along with the Society’s armour. In July 1642, the Inn paid for the refurbishment of its muskets ‘for new stocks, locks and for other trimming of eighteen old musket barrels’, modernising them for the coming war.

English matchlock muskets renovated in 1642, c.1600-c.1630

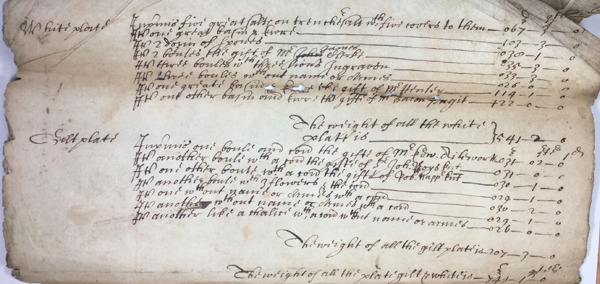

Most of the armed conflict took place between 1642-1646 until Charles I was captured for the first time – he would later escape and restart the war. Those four years caused great financial hardship for the Middle Temple that they were extremely ill prepared for. The Inn had accrued a large debt to John Bayliffe, the Under Treasurer, just prior to the war. Dilapidated buildings were rebuilt, but the cost of the project massively overran and Bayliffe paid the tradesmen out of his own pocket on the expectation of re-imbursement. The Society entered into the disruption of the Civil War on poor financial footing and they spiralled further into debt due to a drastic reduction of admissions to the House and chambers. As a result, the Inn’s collection of silver-plate was sold to pay its debts in 1649.

List of silver-plate owned by the Middle Temple, 1637-1638, sold in 1649 (MT/2/TAS/1)

Normal activity at the Inn ceased completely – no commons were eaten in Hall and learning exercises stopped for several years. As a result of the lack of people coming to the Inn, shops within the precinct suffered from reduced custom. In 1643, Samuel Joscelyn, a stationer based in the Churchyard, petitioned to have his rent reduced. This petition was granted, but the Society’s Pannierman, who received a portion of this rent, had his income reduced by 20 shillings a year. On 29 October 1647, reduced rent was granted to Mercie Meighan, a widow with a shop by Middle Temple Gate, who was suffering from the hardness of the times and the high rates of taxes. On 6 February 1646, the Masters of the Bench attempted to encourage the return of members and students to keep commons and perform exercises in the upcoming vacation by promising that they would be ‘accepted with special favour’. The numbers of people coming to the Inn slowly recovered and it was reported on 13 May 1647 that ‘all passages are open to and fro all parts of the kingdom and there is a competent number of students and barristers, vacationers, met in commons, residing in or about the House and town’. As a result, mooting was restarted on the 18 May 1647.

Order of Parliament that members and students be encouraged to return to the Inn, 6 February 1645/46 (MT/1/MPA/4)

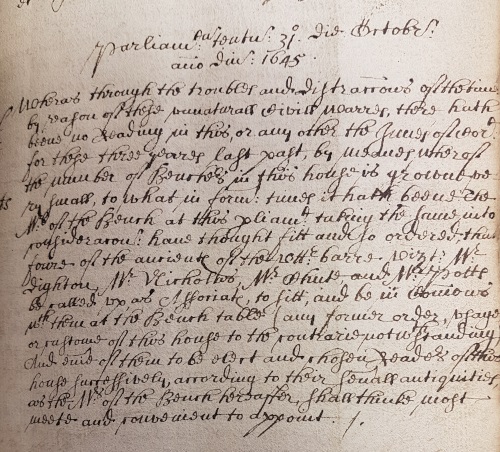

All Readings ceased from 1642 and did not restart until the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660. The cessation of readings quickly became a problem for the Inn, as until this time the condition of admission to the Bench was to have been a Reader. The number of Benchers fell, some dying and others fleeing the city to join the Royalists, but it was not possible to increase their numbers under the existing rules. In response to this problem, it was ordered on the 31 October 1645 that the senior members, known as ‘ancients’, of the Utter Bar be Called as Associate Benchers and be allowed to be in commons with Masters of the Bench. From this time onwards, Benchers were elected to the Bench without being required to Read beforehand.

Order of Parliament that ancients of the Utter Bar be Called as Associate Benchers, 31 October 1645 (MT/1/MPA/4)

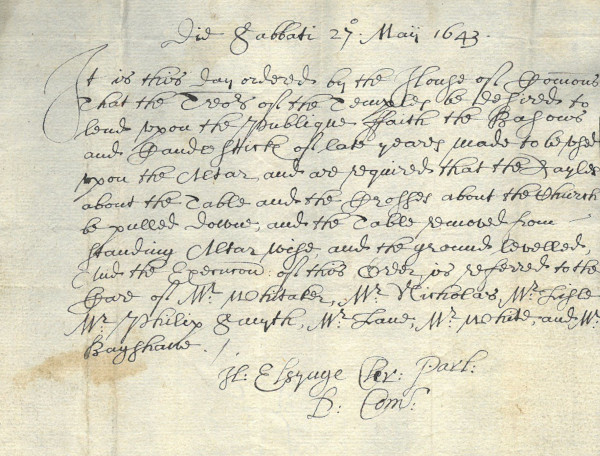

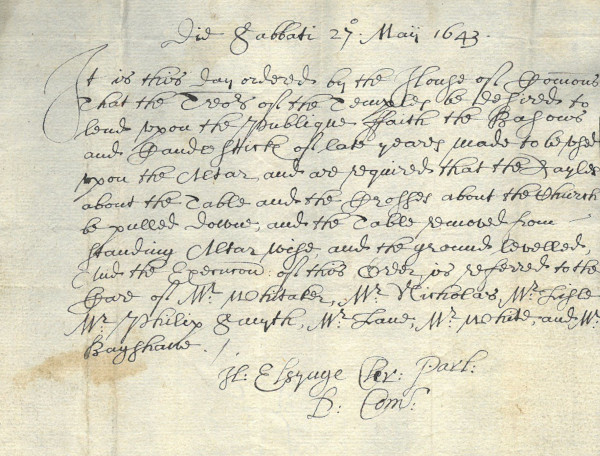

By virtue of the Middle Temple’s position next to the Cities of London and Westminster, which were staunchly Parliamentarian, the Inn was forced to live under the rule of the House of Commons regardless of the loyalties of the Benchers members and officers. During this period, there was an unprecedented amount of interference by the state in the governance of the Inn, with the House of Commons issuing direct orders to the Parliament of the Society. The first surviving order that was issued concerned the contentious matter of religion. On 27 May 1643, the House of Commons commanded that the ‘Treasurers of the Temples be desired to lend upon the public faith the basons and candlesticks of late years made to be used upon the altar and are required that the rails about the table and the crosses about the church be pulled down and the table removed from standing altar-wise, and the ground be levelled’. This order rejected the importance that High Anglicanism placed on the altar, destroying its trappings and using them to fund the Parliamentary war effort.

Order of the House of Commons concerning the destruction of the altar at Temple Church and acknowledgment of receipt of silver plate, 27 May 1643 (MT/15/TAM/80a)

Print of soldiers destroying the ‘popish’ altar and religious symbols at York and the English and Scots armies meeting as friends, 1642 © The Trustees of the British Museum

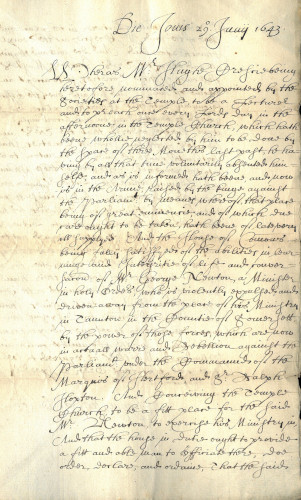

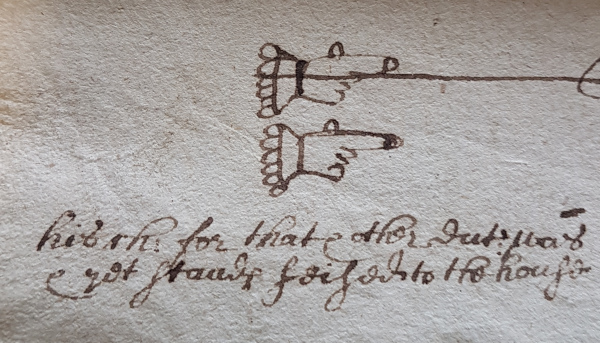

After destroying the altar at Temple Church, the Commons issued penalties on the clergy of the church that had fled to join the Royalist forces. On 29 June 1643, they ordered that the Reader, Hugh Crescie, be replaced as he had been absent for three months in the army of the King. He was replaced by George Newton, a minister who had been ‘violently expulsed and driven away from the peace of his Ministry in Taunton in the County of Somerset by the power of those forces, which are now in actual war and rebellion against the Parliament under the Command of the Marquis of Hertford and Sir Ralph Hopton’. Measures were taken against the Master of the Temple, John Littleton, and his curate Pearson on 27 November 1643. It was ordered that neither of the Inns were to send any money to them that they would usually be entitled to receive – to do so would be to aid the cause of the King through the provision of financial resources. On 11 October 1645, Littleton’s position was sequestered away from him altogether and granted to a new Master of the Temple, John Tombes.

Order of the House of Commons concerning Hugh Crescie, Reader of Temple Church, 29 June 1643 (MT/15/TAM/81)

In early 1643, Parliament formed the Committee of Lords and Commons for Sequestrations to allow the confiscation of the goods and estates of the King’s supporters, which would deprive the enemy forces of both financial and material assistance. The sequestrations of these estates were of dubious legality, and there were many appeals against them. The legal profession in London was active in hearing these appeals, untangling the evidence and providing a façade of legitimacy to the practice. However, those members of the legal profession that fled the capital to join the Royalist forces became victims of the sequestrations.

Note regarding seized chambers in the margin of the Treasurer’s summary of annual accounts, 1642-1646 (MT/2/TAS/5)

In January 1644, the Inn’s blacksmith was paid to padlock the chambers of known Royalists to prevent the contents being accessed by the absent occupants. The Commons began targeting named gentlemen for confiscation of chambers. On 13 February 1644, they ordered that the chambers of Sir Richard Lane, who was later appointed Lord Keeper of the Great Seal by the King, were to be confiscated and granted, with garden, goods and books, to Bulstrode Whitelocke, Member of Parliament for Great Marlow and one of the Commissioners appointed to treat with the King. Whitelocke was not elected to the Bench until 1648, and as a result Lane’s former chambers had to be discharged from all privilege as a Bencher’s chamber in order to adhere to the order. On 26 October 1644, the Inn was presented with a similar order concerning the chamber of the Bencher, George Beare, which was granted to Robert Nicholas and that same day it was ordered that Sir Edward Hyde be replaced in chambers by Robert Reynoldes.

Blacksmith’s receipt including charges for padlocking chambers, January 1644/44 (MT/2/TRB/4)

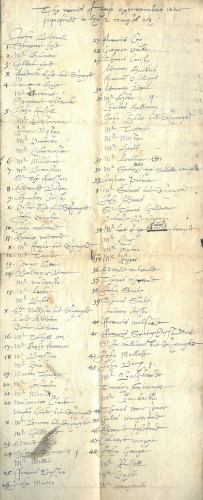

In 1644, the House of Commons ordered that the Society provide a list of names of gentlemen who either presently or had recently occupied any chamber or part thereof in the Inn, and that they provide the means by which they could be identified. No assignments of chambers were to be made until further orders from the Commons, and the chambers, goods, chattels and books of named Royalists were to be seized. A list survives of one-hundred and two gentlemen who had their chambers sequestered across the Middle Temple and Inner Temple, and a note at the end of the list indicates that warrants were issued for further seizure of chambers not mentioned on the list. Many of the individuals and families who fell victim to sequestrations were rendered destitute and deeply traumatised by the experience of losing their property.

List of names of members of the Middle Temple and Inner Temple whose chambers were sequestered, c.1644 (MT/1/MIS/3)

The penalties for supporting the King were severe and the Inns attracted the suspicion of those that wished to root out these dangerous elements in 1649. On 8 June, it was reported at the Inn’s Parliament that the Lord Chief Justice had communicated with the Masters ‘touching an affray, or some abuse offered to the soldiery as they passed along by the Temple Gates in Fleet Street’. It was thought that one of the gentlemen of the Middle Temple or Inner Temple was involved and that ‘persons who ought not to lodge in the Temple were there harboured, and that others sheltered themselves there from justice’. The Inns were being accused of harbouring supporters of the King ‘of which the consequence, in these crazie and fickle times, might have bin very dangerous’. All officers and servants had their chambers searched ‘to know what strangers harbour or lodge therein’ in order that the Society ‘give answer and satisfaction to the State touching their peaceable deportment and behaviour here’.

Assassination of Isaac Dorislaus, a Dutch Calvinist historian and important official during Oliver Cromwell’s rule, by masked Royalists, 1649 © The Trustees of the British Museum

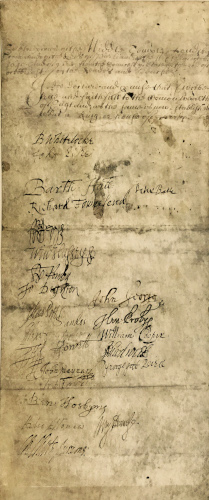

After the execution of King Charles I in 1649, a declaration of loyalty to the Commonwealth, called the Declaration of Engagement, was proposed. This would require members of the Council of State to sign and thereby express their approval of the King’s trial and execution, as well as the abolition of the monarchy and the House of Lords. After objections to this declaration, a compromise was reached where signatories would declare loyalty to the new Commonwealth, but not be asked to approve of its past actions. In October 1649, the requirement to sign was extended to all Members of Parliament, clergymen, members of the armed forces, courts of law, municipal government, and schools and universities. The declaration was signed by members of the Middle Temple and includes the names of twenty-four Benchers and twenty-seven members of the Bar. One of the Benchers, John Lisle, was infamously known as a regicide for signing the death warrant of the King.

Extract from the Declaration of Allegiance to the Commonwealth of England, 1649 (MT/1/ALL)

The Civil War violently polarised the country and left extreme levels of trauma following the atrocities and destitution caused by the conflict. The Middle Temple would not be the same as it was before the war – Royalist members were cast out of the fellowship of the Society, Readings ceased altogether until a brief revival in the 1660s and 1670s, the process of electing Benchers changed, and the Inn’s collection of prestigious silver was sold to pay its debts. It is likely that a shadow was cast over the previously merry Hall for a long time afterwards and the divisions that remained in England long after the fighting ended also poisoned the atmosphere of the Inn. Despite the challenges of those ‘sad, distracted tymes’, the Middle Temple would adapt and flourish again in the centuries to come.