For centuries, the Middle Temple, its members and guests have been protected and served by generations of porters and watchmen. This month, we look at how these roles have evolved and the often dramatic stories of the men who held these offices over the years.

The earliest reference to a porter in the Middle Temple Archive appears in the Minutes of Parliament for 1587, when one William Carter requested 'certain wages as Porter'. Carter remained in post for twenty years, and in 1589 an order of Parliament continued his pay 'for his pains in keeping the House and keeping the gates locked every night', and in 1602 he was ordered to 'keep the Hall door at dinner, supper and breakfast times to keep out strangers and such as are not of the house'. For his work, he received 55 shillings a year, and was provided with accommodation in the Inn and allowed 'to have the old kitchen'.

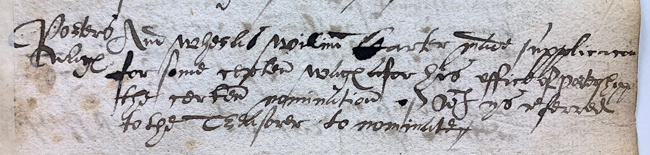

Order concerning William Carter’s petition for wages, 24 November 1587 (MT.1/MPA/3)

Carter's successor, Philip Walker, also benefited from accommodation in the Inn, subject to certain conditions: it was ordered on his appointment that 'he shall have a convenient room on the east side of the Temple Gate, provided that he bring not in his wife nor family to inhabit there, and that no victualling, tippling, nor unlawful games be used there'. Evidence suggests that Walker was not always diligent in his duties - in 1614 he was deprived of food from the kitchen 'for his remissness', and threatened with dismissal 'if he do not speedily amend and reform the disorder of company extraordinary standing at the screen at dinner and of beggars in the lane'.

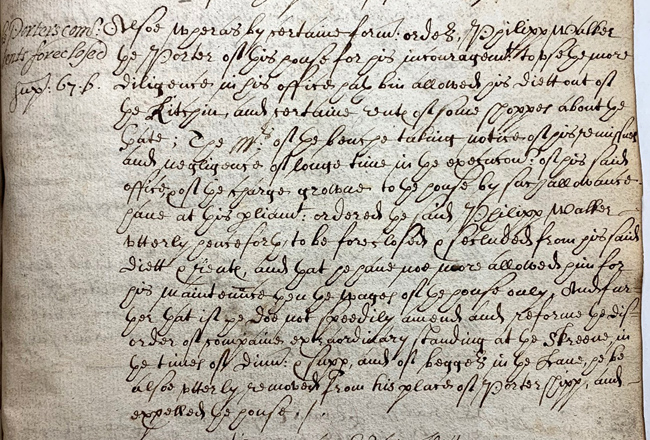

Order concerning Philip Walker’s ‘remissness’, 26 November 1624 (MT.1/MPA/4)

The duties of the Porter were, then, chiefly to keep undesirables out of the Inn and prevent them from harassing those dining in Hall. An order of Parliament in 1652 also names the Porter as one of the officers appointed to carry corpses, and in 1654 a fuller account is given of the increasingly varied role, which required the incumbent to 'industriously keep clean the courts, look to the gate and House, and at least once every night walk about the courts and up every stairs to prevent robberies, which have lately been often committed' and to 'keep out of the House all vagrant people who cry 'milk' or any other thing, not usual and proper to this Society.'

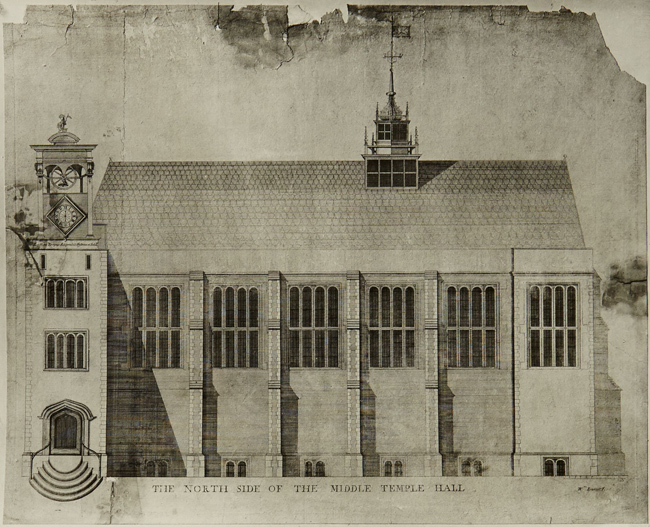

‘The North Side of The Middle Temple Hall’, engraving by William Emmett, 1700 (MT.19/ILL/D/D1/39)

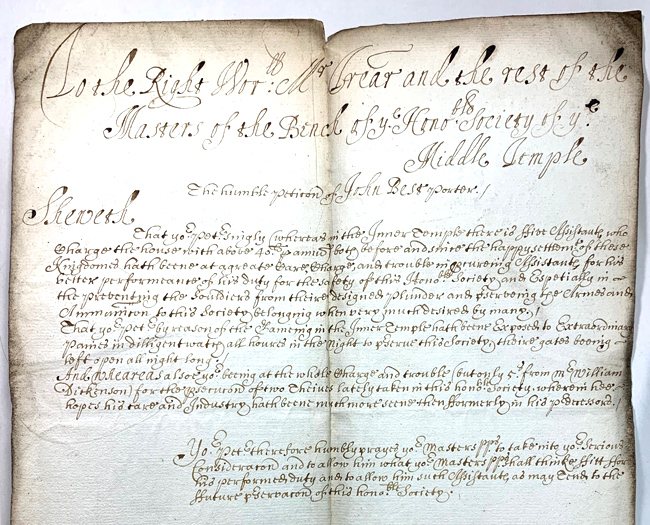

Historical exigencies led to porters taking on more daunting duties. In 1659, the country was plunged into turmoil by the collapse of the Cromwellian Protectorate, leading eventually to the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660. Evidently this disruption reached the Temple, for in 1659/60 the Porter, John Best, was awarded £5 'as a gratuity for his labour in these times of trouble', possibly in response to his petition for assistance in 'keeping watch and preventing the soldiers from plundering the arms and ammunition, very much desired by many'.

Petition of John Best for assistance in watching over arms and ammunition, c1660 (MT.21/1/2/1/5)

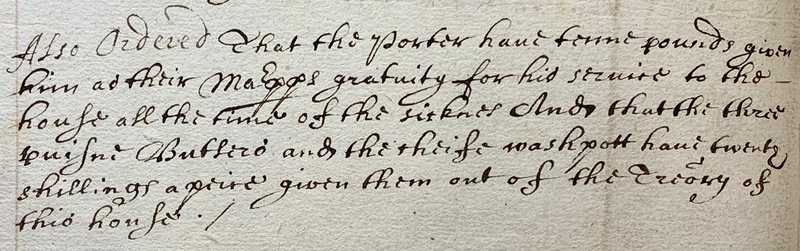

Not many years later, London was hit by the Great Plague, and the Inn was deserted, grinding to a halt with a skeleton staff remaining to keep things secure. Best seems to have played a part here, for Parliament ordered that 'the Porter shall have £10 gratuity for his service during the sickness'. Sadly, he had not much time to enjoy this windfall, and was himself dead within six months, though whether or not from plague is unknown.

Order that the Porter have £10 for his service during the sickness, 9 February 1665/6 (MT.1/MPA/6)

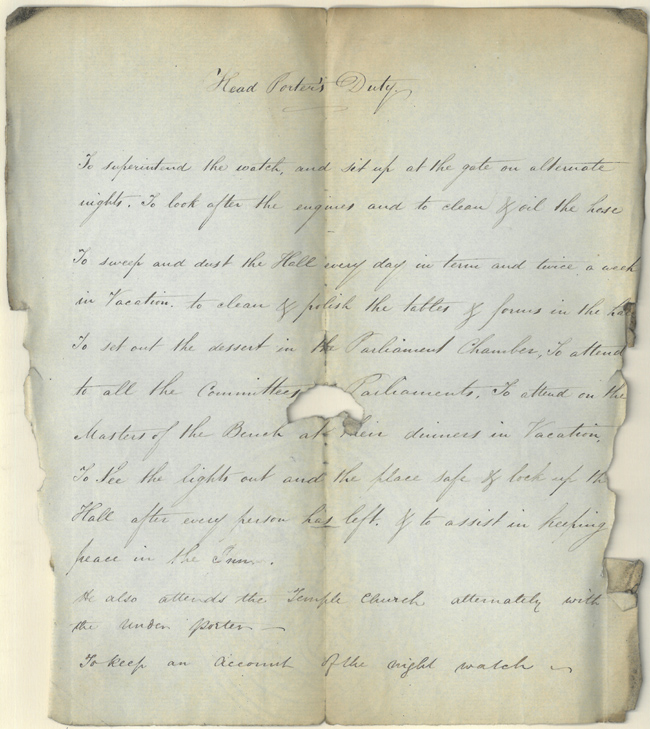

The role evolved throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In the winter of 1716-17, the Porter was put to 'unusual charge and trouble in cleaning and clearing the several Courts... of great quantities of ice and snow' and in 1719 the Porter's Assistant was paid a bonus for apprehending a thief armed with 'divers very dangerous tools'. By the nineteenth century, the role of the Head porter had expanded to include superintendence over the watch, manning the gate on alternate nights, looking after the fire engines, sweeping the Hall, setting out dessert in the Parliament Chamber, attending to all committees, attending in Temple Church, and 'keeping peace in the Inn'.

Account of the Head Porter’s Duties, (MT.21/1/40/2/19)

Even when London wasn't being ravaged by plague or political turmoil, dangers abounded for the porters. Henry Anott had a particularly rough time of it in 1631, Parliament recording that one Southcott, a student of the Inn, was fined £5 'for breaking the head of Henry Anott, the Porter', and on the same day John Smith, porter to the steward, was 'excluded from the House for abusing Henry Anott... and for calling his wife whore'. A century later, the Porter's widow, Mary Machon, appealed to the Bench for charity, stating that as a result of 'the sudden fall of the Great Gate upon him by reason of a very high wind', her husband's days had been shortened and he had been left incapable of continuing his duties'.

The Great Gate and Temple Bar, 1800 (MT.19/ILL/E12)

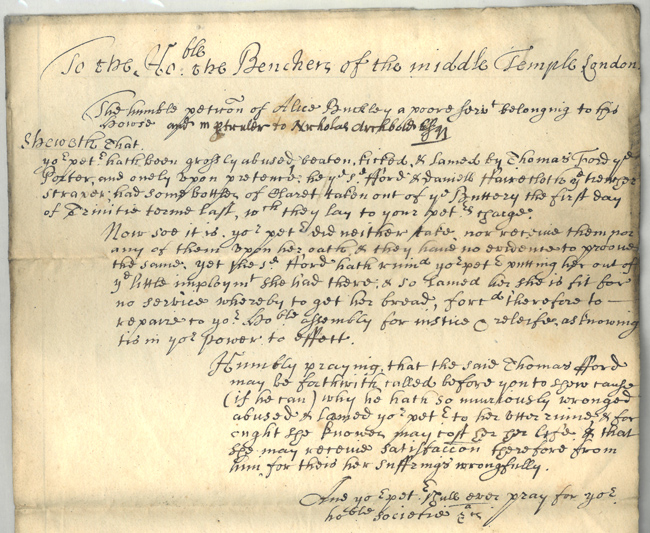

Porters themselves were not always particularly well-behaved. A petition to the Benchers dating to the late 1600s from one Alice Buckley, a Middle Temple laundress, complains that she had been 'beaten, abused and lamed' by Thomas Ford, Porter from 1671 to 1694, and demands that the Inn take action. No record survives of this disturbing matter being discussed, let alone resolved, though the Minutes of Parliament do record that Ford was fined for having been 'active and instrumental' in certain 'misdemeanours and insolencies' on the part of a group of Middle Templars in 1674.

Petition of Alice Buckley concerning her abuse by Thomas Ford (MT.21/1/2/7/9)

Reports of bad behaviour continue throughout the nineteenth century. In 1848, a complaint reached Parliament of Henry Ing, Under-Porter, having struck a child with a cane for making mischief in Fountain Court, an act described by the child's father as one of 'wanton bestiality'. In the summer of 1856, Charles Ing, after a morning's work, retired to a nearby public house and, after several pints (appropriately enough of porter), wandered back to the Inn. Various reports indicate that he was loitering around, generally drunken and insolent, and he was eventually turned out of the Inn into the hands of the City Police.

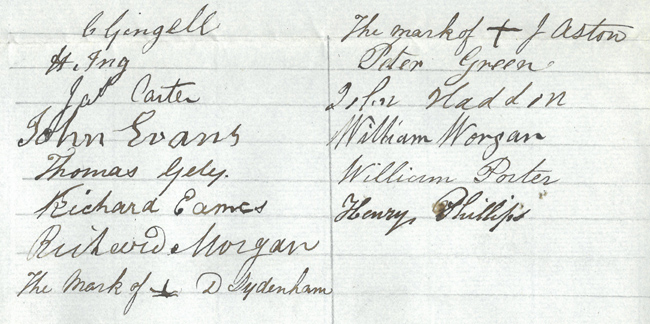

A running theme in the records is the clothing worn by the Inn's porters. There are early references in the Minutes of Parliament to funds being released for porters' gowns. A written petition dating from the nineteenth century and signed by the porters, warders and watchmen complains that 'their present apparel is insufficient for the severities of the weather to which they are liable to be exposed'. They request that they be furnished with 'Watch-coats similar to those furnished to the Inner Temple watchmen'.

Signatures (and marks) of porters, warders and watchmen on a petition for watch-coats, 1838 (MT.21/1/8/1/21)

Porters were also distinguished by silver badges, to which records refer as far back as the seventeenth century. The Inn's silver collection includes a Head Porter's badge dating from around 1685, made by one Thomas Jenkins. Substantial in size (see below), it is adorned with the emblem of the Lamb and Flag, and a bill for its purchase can be found in the Treasurer's Receipt Book for 1685. Seven smaller badges dating from the nineteenth century embossed with the words 'Watchman', 'Porter' or 'Warder', also remain in the collection.

Badges of the Head Porter, porters, warders and watchmen

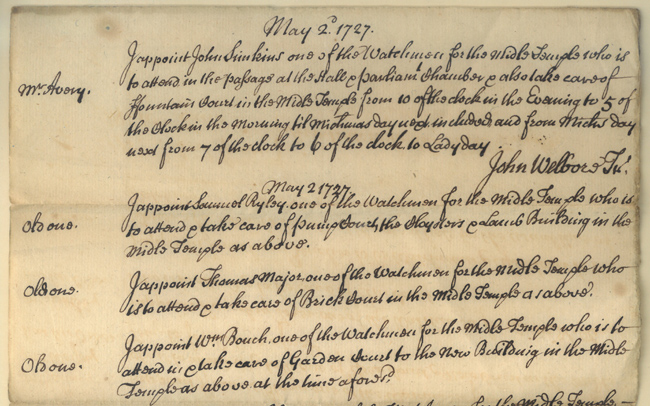

In their care for the Inn's security, the porters were assisted ably by teams of warders and watchmen. An early 17th century bill records a payment for 'fower watchmen at Christmas when the play was in the Hall to watch the Hall windowes and to keepe them from breaking'. A list from 1727 details the different courts watchmen were appointed to keep watch over - for example, John Simkins was tasked to watch the Hall, Parliament Chamber and Fountain Court, while Samuel Ryley took on Pump Court, the Cloisters and Lamb Building.

Appointments and duties of watchmen, 1727 (MT.8/SMP/41)

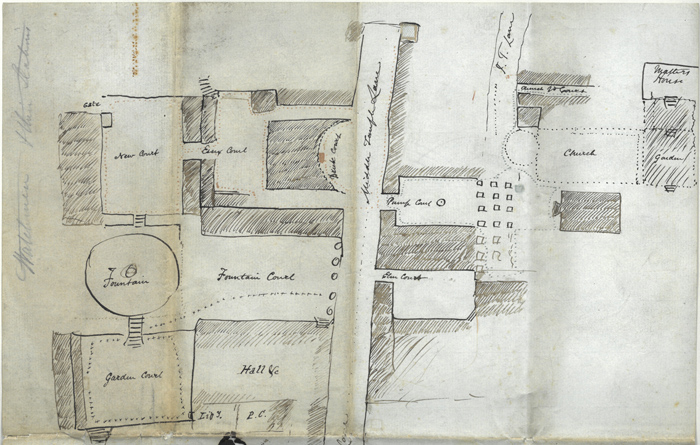

A hand-drawn plan of the Inn from the 1850s has survived in the archive, which shows the different beats about the Inn to be kept by the watchmen. It also indicates some of the ways in which the Victorian Inn differed from the Middle Temple of today, particularly in Essex Court and Brick Court, and the location of the Library.

Plan of the beats of watchmen around the Inn, c1850 (MT.8/SMP/147)

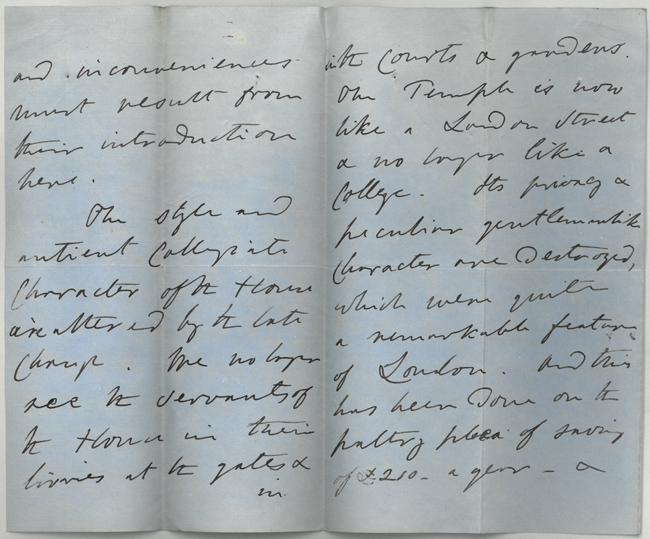

In 1857, Parliament decided to streamline its internal force of porters and watchmen, and for the first time in history allow the City Police to patrol the Inn. This led to uproar from various resident members and letters poured in. Sir George Bowyer expressed regret that one no longer saw the 'servants of the House in their liveries at the gates', and that the Temple was 'like a London street... its peculiar & gentlemanlike character destroyed.' He called into question the Benchers' authority as a 'self-elected body', and criticised them for giving up an exemption from the City authorities dating back to the days of the Knights Templar.

Extract from letter from George Bowyer to the Treasurer, 1857 (MT.1/PPA)

One Mr Speke complained that on arrival from Paddington late one night, he had been 'obliged to drag my luggage myself up two pairs of stairs to my chambers' due to the recent dismissal of the night porters. Richard Paternoster complained that 'my rest is continually broken every night, my comfort and privacy entirely destroyed and my health materially injured and my chambers rendered untenantable'. Parliament responded early the following year that they saw 'no reason for receding from the arrangement', which seems largely to have closed the matter.

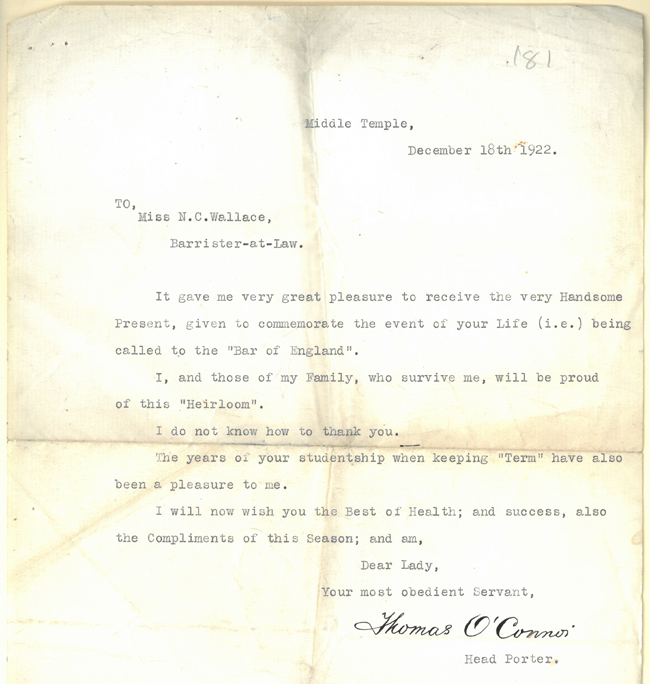

Middle temple porters often became beloved parts of the Inn's furniture. Thomas O'Connor was one such figure - Head Porter for 13 years from 1914, he was present for the first admissions of women to the Inn, starting in 1919. He made such an impression on one of the first cohort of women to be Called to the Bar at the Middle Temple, Naomi Constance Wallace, that she presented him with a gift on the occasion of her call in 1922. His letter of thanks survives in the archive, expressing his 'very great pleasure to receive the very Handsome Present', saying 'I do not know how to thank you. The years of your studentship when keeping "Term" have also been a pleasure to me'.

Letter from Thomas O’Connor to Naomi Constance Wallace, 18 December 1922 (MT.8/SMP/181)

O'Connor's obituary in the Evening Standard a few years later announced that 'Old O'Connor is dead and the Middle Temple mourns'. The respect and warmth he commanded across the Inn is readily apparent from the Standard's words: 'Lord Chancellors would never pass down the lane without acknowledging his salute. He was a man of great dignity. No more immaculate figure ever walked through the Inn'. A photograph shows O'Connor resplendent in his uniform and bearing his staff at the entrance to Hall.

Thomas O’Connor at the entrance to Hall, c1920 (MT.19/POR/520)

The duties of the porters expanded during the Second World War. One was asked by the Under Treasurer to become an instructor in the 'Fire Guard Plan' which, he reminisced, seemed to be 'don't do the obvious thing but do what you want in the most round about way you can possibly conceive'. This particular porter's utter disdain for the plan he had been tasked with disseminating may have saved the Hall from destruction. He recalled the landing of an incendiary canister in March 1944 which set many buildings and the roof of Hall ablaze. According to the Fire Guard Plan they were not permitted to telephone the fire brigade, but to tackle it themselves as far as possible. Undeterred, he made the call, 'and within 15 minutes we had several Appliances at work and the roof of the Hall as all know is almost intact'.

A porter’s recollections of the Second World War, 1946 (MT.1/WAR/41)

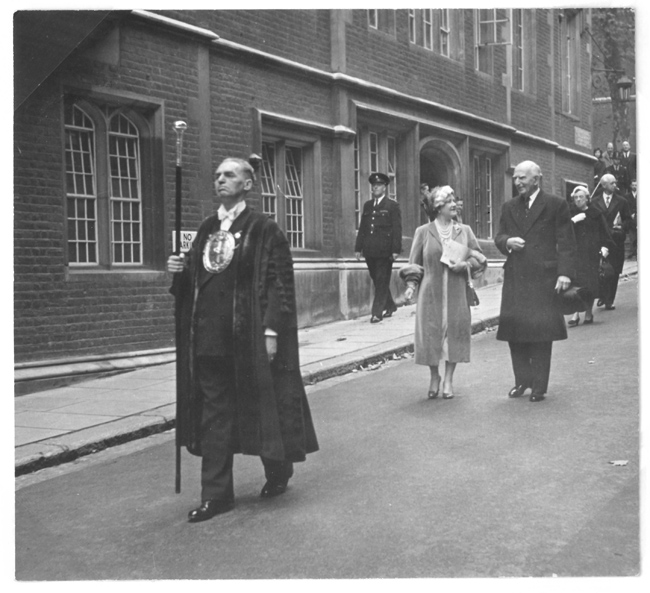

While much of the day-to-day formal livery had been dispensed with by the second half of the twentieth century, it still made an appearance for grand occasions. Photographs of the visit of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother to open the new Library on 7 November 1958 show Her Royal Highness being led down the lane towards the Library by the Head Porter bearing his staff and wearing his gown and badge.

Photograph of the Head Porter leading the Queen Mother to the new Library, 1958 (MT.19/PHO/1/17)

The role of porter continued to develop and change over the twentieth century, and in the twentieth the title itself has disappeared from the Inn. The Front-of-House officers and Security team still keep the Inn safe, secure and running smoothly as they and their predecessors have for centuries, and indeed on important occasions the Head Porter’s gown, badge and staff still make an appearance.