The Christmas Revels are an ancient tradition at the Middle Temple, dating back to the early centuries of the Inn's history, and live on - in slightly better-behaved form - today. These festivities brought much pleasure and merriment to Middle Templars gone by, but also drew censure - from within and without the Inn. The seventeenth-century popularity of 'masques' - courtly entertainment involving music, song and dance in elaborate costumes - was reflected at the Inn, where members often contributed to the expense of staging them to celebrate major occasions. This month we look at these two festive traditions and the archival record they have left behind.

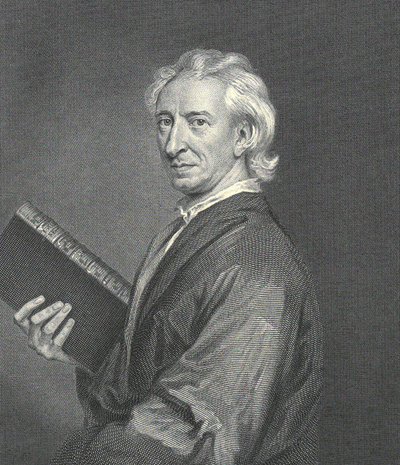

Christmas Revels in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were staged on a rather grander scale than the Inn's modern day equivalent, excellent fun though the latter may be: a contemporary record states that these Christmas pastimes spanned over three months, from All Saints' Eve to Candlemas Day. Much of what we know of the early days comes from external sources. Samuel Pepys records meeting a Madam Turner, who had 'been at the play to-day at the Temple, it being a revelling time with them', and earlier Henry Machyn describes 'grett revels as ever was for the gentyllmen of the Tempull evere day [with] playhyng and synghyng'. The diarist John Evelyn, a Middle Templar himself, took a rather dimmer view of events, describing how in January 1668 he 'went to see the revels at the Middle Temple, which is... an old riotous custom, and has relation neither to virtue nor policy'.

Engraving of John Evelyn (MT.19)

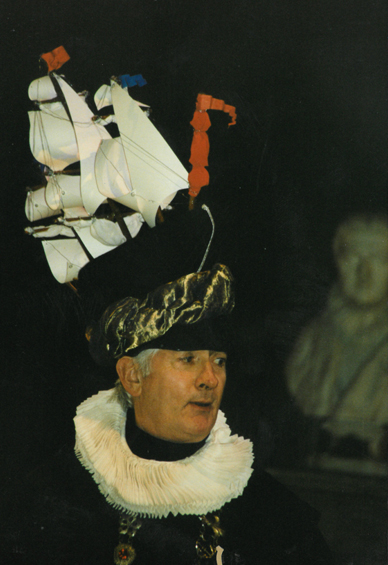

One early account survives of a joint revels of the Middle Temple and Lincoln’s Inn, in 1598. Benjamin Rudyerd writes that the ‘Linconians… invited the Templarians to theyr solemnities entertained them with variety of Musique and ended theyr friendly Revels with a sumptuous banquet’. These revels, lasting for days on end, saw a ‘Sir Martino’ (in fact Richard Martin, a future Bencher of the Middle Temple and Recorder of London, who had been briefly expelled from the Inn some years earlier due to such festive ‘misdemeanours and abuses’) set up as the ‘Prince of Love’. The festivities involved banquets, comedies, dancing, processions of heralds, disagreements and reconciliations between the two Inns, and the ‘sacrifice of love’. In 1998 Master Arlidge celebrated the quatercentenary of this event with a reconstruction of the revels in Hall, entitled ‘The Prince of Love’, which featured a range of characters including Richard Martin and Sir Walter Raleigh, and starred such legal luminaries as Master Arlidge as the Lord Admiral and Master Eleanor Sharpston as Benjamin Rudyerd himself.

Scenes from ‘The Prince of Love’, Middle Temple Hall, 1998 (MT.7/GDE/190)

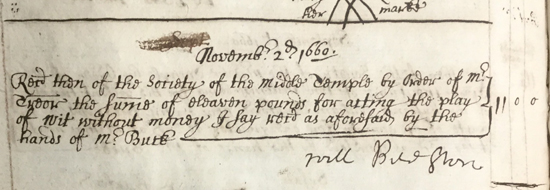

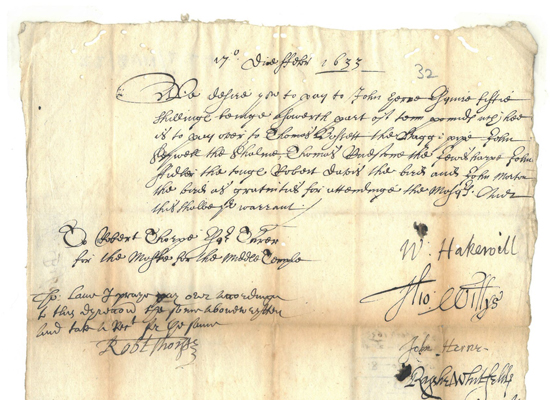

Plays often featured as part of the entertainments at this time of year, as Madam Turner had reported to Pepys, and receipts in the archive name a number of these. One receipt dated 4 th December 1657 records a payment of £5 for music and the performance of ‘The Countryman’, and in 1660 ‘Wit Without Money’ by John Fletcher was put on. It has been suggested that the performance of plays by musicians may have been a way of getting around Parliament’s banning of stage plays and actors in the 1640s.

Receipt for payment of £11 for the performance of 'Wit Without Money', 1660 (MT.2/TRB/19)

Of course, one of the most famous occasions in the Inn's history took place at this time of winter celebrations. On 2 February 1602, the first recorded performance of Shakespeare's 'Twelfth Night' was staged in Hall, as part of the Inn's Candlemas festivities, an occasion which has been commemorated many times over the years, including at Candlemas 1897 with a full performance in Hall. Candlemas also saw the celebrated lutenist John Dowland, one of the King's musicians, and his troupe perform music before the Judges and Benchers at the Inn in 1613.

Cast of 'Twelfth Night', Middle Temple Hall, 10 February 1897 (MT.19/PHO/2/1)

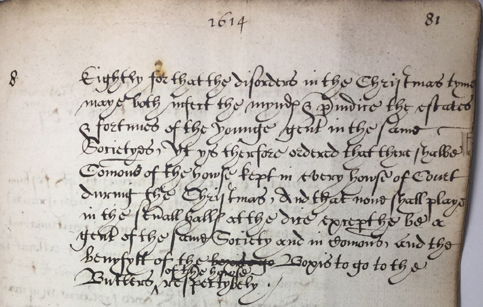

Unruly behaviour beyond plain excess also became a common occurrence at this time. In November 1584, Parliament passed an Order that ‘no outcries in the night shall be made, nor chambers broken open, as by the Lord of Candlemas night’, and in 1614 King James I himself was forced to admonish all four Inns and lay down ten orders for their 'better government'. The eighth of these complained that 'the disorders in the Christmas tyme maye both infect the mynds and preiudice the estates & fortunes of the younge gents in the same Societyes'. Parliament was forever passing orders to ban gambling at Christmas, and in 1630 certain junior members of the Inn, having been censured for their defiance of such a prohibition, began to hurl their pots at the Benchers, who were forced to flee to the Parliament chamber to take refuge.

Eighth order of King James I, concerning Christmas Disorders (MT.1/MPA/5)

Masques also featured as part of the Christmas celebrations at the Inn - masquers could revel with the ladies in the audience free of the usual censure, which may have been an important consideration for those younger Middle Templars who had been reprimanded for concealing women in the minstrels' gallery until the Benchers had departed. Masques were also sometimes performed on a grand scale to mark major royal occasions, notably during the reigns of James I and Charles I. In 1613, a masque was put on by Middle Temple and Lincoln's Inn to celebrate the marriage of King James' daughter. The notable architect Inigo Jones, was engaged to provide the scenery and decorations - he was admitted to the Inn on 21 February 1613.

Engraving of Inigo Jones (MT.19)

A number of years later, in the reign of Charles I, a masque entitled 'The Triumph of Peace' was staged by all four Inns before the King to celebrate the birth of his second son, the future King James II. A taxation was placed upon members of the Inns to fund this, and a number of orders of payment survive associated with the performance, painting a fascinating picture of the event, particularly of the masquers' costumes. Payments were ordered for items including: Florence satin, white taffeta, priests' habits, plumes, roses, 'buskins' (boots), feathers, 'vizards' (masks) and silk stockings. Props included truncheons, chariots and (with evident lack of regard for fire safety) over one thousand torches, and one Thomas Basset was paid a total of 200 shillings for 'playing the bagpipes and Jewish harp and making bird songs'. It must have been quite the spectacle, and the King was 'so much taken with the noble entertainment' that he invited 120 gentlemen of the Inns of Court to enjoy his own masque on Shrove Tuesday.

Order for payment to Thomas Basset for assorted musical efforts (MT.7/MAB/32)

Over the course of the seventeenth century, there was a marked transition towards a milder and more reserved celebration of Christmas. Minutes of Parliament record that the festival should be kept 'solemnly' or not at all, and the ban on a 'gaming Christmas' became embedded. Nonetheless, the mid-1970s saw Revels return to their place at the heart of a Middle Temple Christmas, and assorted records survive in the Archive including running orders, tickets and posters. In 1975 the Revels included such no-doubt memorable numbers as 'A Wandering Bencher', 'Nostalgia is not what it was', 'The case of the Danish Prince' and 'The case in favour of entrails', and in 1976 the Treasurer of the day performed 'The Very Irreverend Angus McSporran'.

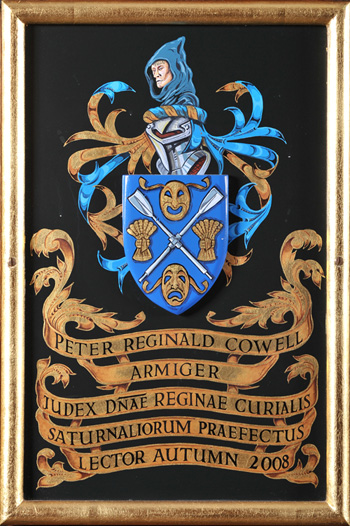

Alongside the revival of Revels themselves, the ancient office of Master of the Revels was resurrected in 1983, to be held by Master Babington, and appears in Latin, as 'Saturnaliorum Praefectus', on the armorial panels of Master Leslie Joseph and Master Peter Cowell in pride of place alongside their legal acheivements.

Armorial Panels of two 21st century Masters of the Revels

The Christmas Revels have, in recent years, continued to entertain, to amuse and - with that old favourite, bangers and mash - to nourish members of the Inn, and this year's, to be performed 14 - 15 December, will doubtless do the same.