Introduction

2019 marked the 100th anniversary of the passing of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act of 1919. The passing of this Act allowed women to become practising solicitors and barristers in an official capacity, and to join the Law Society and the Inns of Court: “a person shall not be disqualified by sex or marriage from the exercise of any public function, or from being appointed to or holding any civil or judicial office or post, or from entering or assuming or carrying on any civil profession or vocation, or for admission to any incorporated society (whether incorporated by Royal Charter or otherwise), and a person shall not be exempted by sex or marriage from the liability to serve as a juror”.

As a result of that legislation, the first woman to be called to the Bar on 10 May 1922 was Ivy Williams, a member of Inner Temple. Helena Normanton was Called to the Bar at Middle Temple in November 1922.

A Women in the Law exhibition was held in the Library from January to April 2022 which aimed to highlight women in the law by discussing the pioneers in the profession as well as ‘hidden’ women in professions associated with the law, displaying texts aimed at explaining the law in relation to women and legislative attempts to gain equal rights for women.

Below are some of the items it featured.

Legislating women

Dr. Gillian Murphy, Curator of Equality, Rights and Citizenship at LSE Library

Josephine Butler took a leading role in the campaign to repeal the Contagious Diseases Acts of 1864, 1866 and 1869. The Acts attempted to reduce the cases of venereal disease among military and naval service men by circumscribing women’s freedom in public places. The Acts only applied to women, and not men. By 1869, there were 18 ‘protected’ areas covering garrison depots and ports in Southern England and Ireland. Under the Acts, a woman who was identified, or even suspected, of being a prostitute, could be forced to have an internal medical examination by a military or naval officer. If diseased, she would spend at least a year in a ‘lock’ hospital and receive further internal examinations. Her name would go on a police register of ‘common prostitutes’. There was no right of appeal.

In campaigning against these Acts, Josephine Butler challenged middle-class Victorian conventions on different levels. First, she spoke in public about sexual behaviour, sharing platforms with men, all of which were thought scandalous at the time. She also brought into the open the sexual double standard prevalent in Victorian society. The campaign achieved its aim in 1886 and its success was largely due to Butler’s activism.

Butler continued campaigning to raise awareness about the trafficking of young girls into prostitution in Britain and continental Europe and founded the International Abolitionist Federation. She also campaigned around the age of consent, raising it from thirteen to sixteen.

‘Ladies’ law’: The law in relation to women

Works relating to women’s legal rights have been published in Britain since at least 1632, when ‘T.E.’ published The Lawes Resolutions of Women's Rights, this book focuses on three stages of a woman’s life, as delineated in the early modern period: spinster, wife and widow. It was entered in the Stationers’ Register to the bookseller John Grove “under the handes of Sir Egremont Thynne and Thomas Edgar” on the 30th of April 1632. ‘T.E.’ most likely refers to Edgar, who is often named as the editor of this work, although the work has also been attributed to Sir John Doddridge (1555-1628), the author of The compleat parson and The English lawyer.

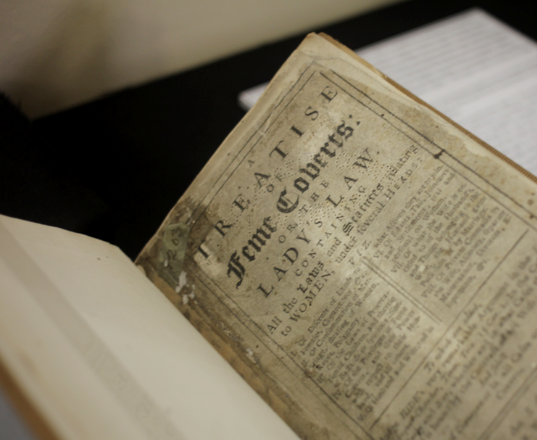

Baron and feme. A treatise of the common law concerning husbands and wives was an anonymous work published in 1700. While not strictly focused on women’s legal rights, it does discuss the law of husband and wife (‘baron and feme’) and marriage, which would, of course be of relevance to women in the 18th century. It was reissued in 1719 and 1738. A treatise of feme coverts or, the lady’s law was published in 1732, purporting to contain ‘all of the laws and statutes relating to women’. This work was reissued in 1737 as The lady's law or, a treatise of feme coverts.

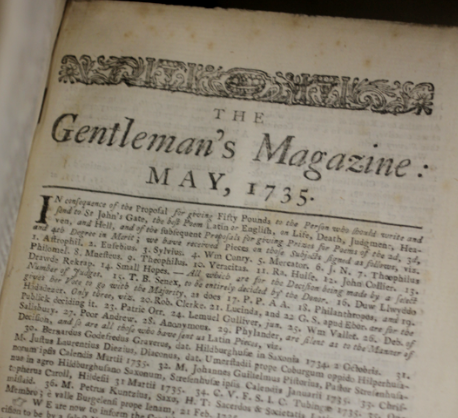

In 1735 Sarah Chapone (neé Kirkham) published The hardships of the English laws in relation to wives anonymously. Parts of it were excerpted in the May and June 1735 issues of the Gentleman’s Magazine. Chapone’s work examines the subjection of women and their legal status as wives. She outlines several cases of the abuse of women in the law, and the scant legal protection they were afforded.

Chap one uses two cases to illustrate the mistreatment of women. In Case II, she describes how a woman was mistreated by her husband (meaning, presumably, that she was beaten or worse). She fled to safety, staying with her brother. The husband insisted that she return, ordering that “her brother … send her home again”. Her brother was forced to “deliver her up”.

one uses two cases to illustrate the mistreatment of women. In Case II, she describes how a woman was mistreated by her husband (meaning, presumably, that she was beaten or worse). She fled to safety, staying with her brother. The husband insisted that she return, ordering that “her brother … send her home again”. Her brother was forced to “deliver her up”.

Within a month she was dead.

The 1777 Laws respecting women is divided into four parts dealing with the legal status of women, including proprietary rights, marriage law, criminal law and family law. It also includes an account of the trial of Elizabeth Chudleigh, Duchess of Kingston, for bigamy. Elizabeth had colluded with her first husband, John Hervey, to conceal their marriage, and subsequently married Evelyn Pierrepont, 2nd Duke of Kingston-upon-Hull.

Many more books were published during the 19th and early 20th centuries, including J.J.S. Wharton’s An exposition of the laws relating to the women of England (1853), Women and law (1896) by Elizabeth C.W. Elmy, Annie B.W. Chapman’s The Status of women under English law (date unknown) and Women under English law by Maud I. Crofts (1928).

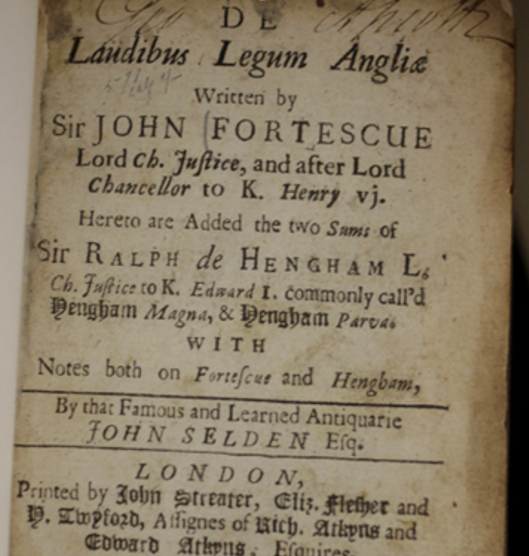

John Fortescue, De laudibus legum Angliae, 1672. First written circa 1470; first printed circa 1543. Sir John Fortescue (1385-1479) was a prominent judge best known for this book, ‘In praise of the laws of England’. It is celebrated for the moral principle that it is better for the guilty to escape than the innocent be punished. It was written as an instruction book, in the style of a dialogue, for Edward, Prince of Wales.

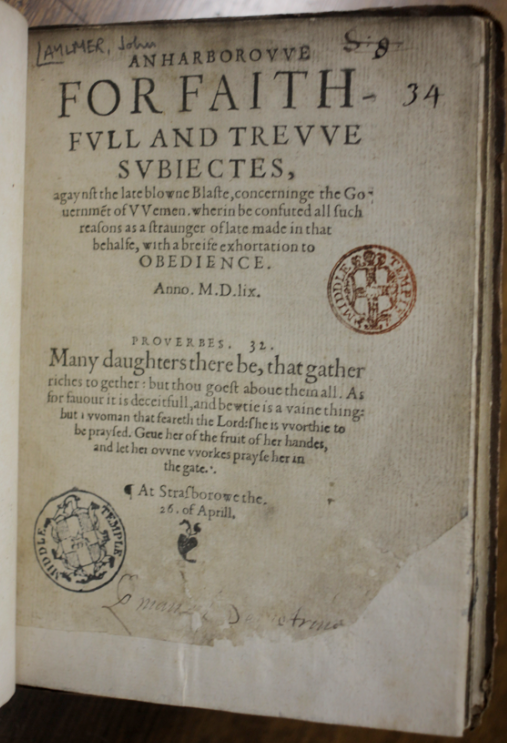

John Aylmer, An harborovve for faithfull and trevve subiectes, agaynst the late blowne Blaste, 1559. Aylmer was Bishop of London but fled to Switzerland during the reign of Mary I. While there he wrote this treatise, in response to John Knox’s Blast against the monstrous regiment of women. In this work he attempted “to repair the damage inflicted” by Knox’s work, which argued against the rule of women. The imprint is false: the book was printed in London by John Day, not in Strasbourg. Aylmer’s book is not exactly a glowing recommendation for women rulers, however. Instead, he argues that Elizabeth I’s personal qualities are what commend her as a monarch despite the fact that women are weak in nature, soft in courage and unskilled. Aylmer returned to England in March 1559.

Repair and restoration

An harborovve for faithfull and trevve subiectes, agaynst the late blowne Blaste is one of several books in our collection in need of restoration. The binding is loose and some of the spine is missing, so it will need a reback and a repair to the spine. The textblock is dirty and needs to be cleaned by hand. There are also some paper tears to repair. This is a defense of the female monarchy during the time of Elizabeth I, and is a reply to The first blast of the trumpet against the monstruous regiment of women by John Knox. The imprint is false – it says Strassbourg on the title page but was printed in London by John Day, which makes it significant as not that many copies of it exist. The cost of repairing this book is £400.

If you would like to sponsor the repair of this, please contact the librarian: r.satterley@middletemple.org.uk. You can also offer a donation via our sponsorship form. Read more about our rare book sponsorship programme.

The lavves resolutions of womens rights, 1632.

In addition to explaining a woman’s rights in marriage, this work covers a variety of topics including “age of consent, dower, hermaphrodites, polygamy, wooing, partition, chattels, divorce, [etc].” According to research carried out by Wilfrid Prest, the book’s intended audience was most likely law students at the Inns of Court in addition to learned gentlewomen, due to the complexity of the text and multiple uses of common law jargon. Its publication in English, rather than law French, however does indicate a certain degree of accessibility. It is the first book in English to use the phrase ‘women's rights’. Wilfrid Prest and T. Stretton have shown that female litigants were prevalent during the Elizabethan and Stuart periods, with some of the best-known being Bess of Hardwick, Lady Joan Thynne and Lady Anne Clifford.

It is very possible that Lady Anne Clifford would have read, in The lawes resolutions of womens rights, that “a female may be preferred in succession before a male by the time wherein she cometh: as a daughter or daughter's daughter in the right line is preferred before a brother in the transversall line, and that as well in the common generall taile, as in fee simple... also a woman shall bee preferred propter jus sanguinis ... land discended must alwaies goe to heires of the blood of the first purchaser, and the case may bee such that a female shall cary away inheritance from a male.” Despite this assertion however, by the 17th century, female inheritances were being diverted away to transversal male lines. For example, Lady Anne’s father, George Clifford, willed the Clifford family estates to his brother Francis and Francis’s heirs in 1605. This led to long legal battles for Lady Anne which were not resolved in her favour. It was not until the death of her cousin Henry that she finally inherited the estates as he died without issue in 1643.

It is very possible that Lady Anne Clifford would have read, in The lawes resolutions of womens rights, that “a female may be preferred in succession before a male by the time wherein she cometh: as a daughter or daughter's daughter in the right line is preferred before a brother in the transversall line, and that as well in the common generall taile, as in fee simple... also a woman shall bee preferred propter jus sanguinis ... land discended must alwaies goe to heires of the blood of the first purchaser, and the case may bee such that a female shall cary away inheritance from a male.” Despite this assertion however, by the 17th century, female inheritances were being diverted away to transversal male lines. For example, Lady Anne’s father, George Clifford, willed the Clifford family estates to his brother Francis and Francis’s heirs in 1605. This led to long legal battles for Lady Anne which were not resolved in her favour. It was not until the death of her cousin Henry that she finally inherited the estates as he died without issue in 1643.

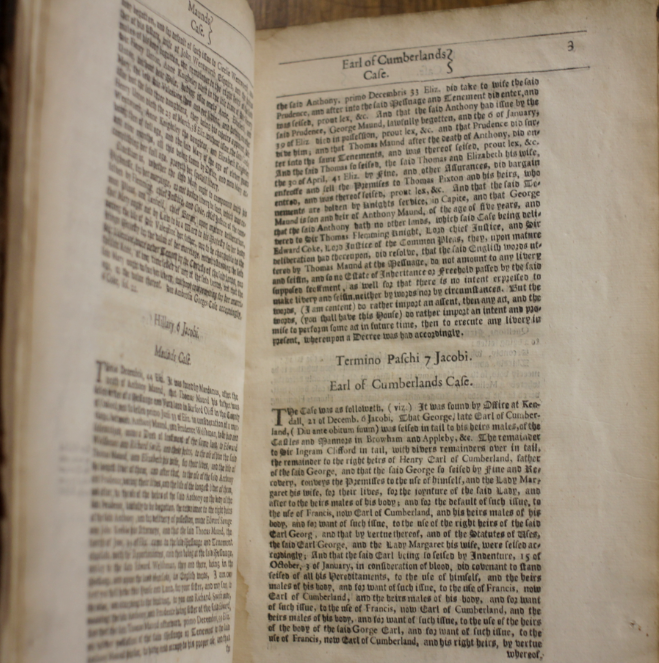

See Earl of Cumberland’s Case

Ley’s King’s Bench Reports

Earl of Cumberland’s Case, 1609 Ley 3

Lady Anne Clifford spent more than thirty years fighting a legal battle to regain the family estate that her father, the Third Earl of Cumberland (George Clifford) had willed to his brother Francis in 1605. Upon Francis’s death, the estate was inherited by Francis’s male heirs and not Lady Anne. Although her legal battles to regain the estate were unsuccessful, she did finally inherit it upon the death of her cousin Henry in 1643, who had died without issue. Throughout her legal battle, Lady Anne refused to agree to cash settlements to forego the inheritance, despite strong attempts by her husbands and James I to dissuade her from pursuing her rightful inheritance.

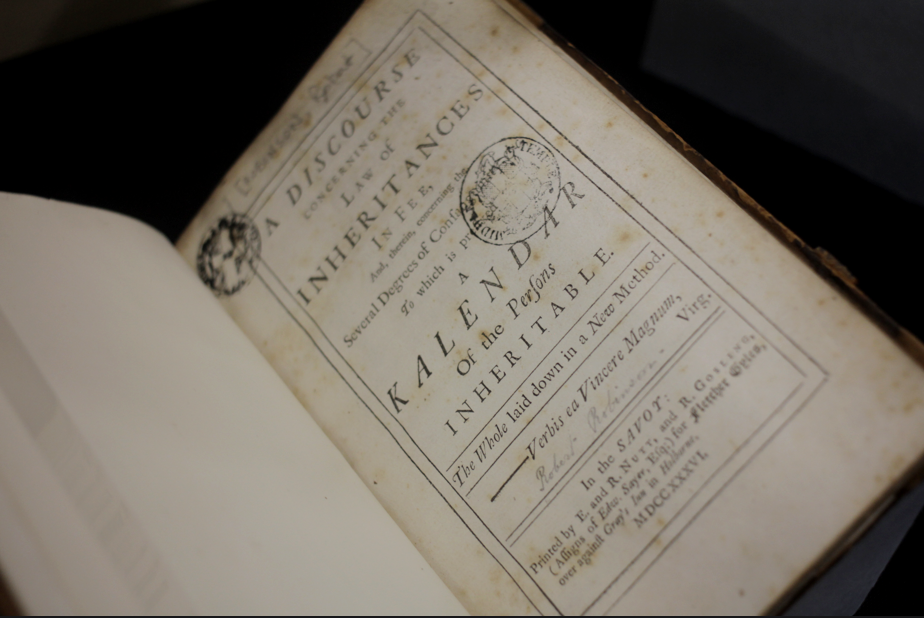

Robert Robinson, A discourse concerning the law of inheritances, 1736.

This tract was written by the Chief Justice of Gibraltar and is open to display his (sadly not unique) view of women in relation to consanguinity and inheritance. Robinson argues that women are simply bearers and do not contribute to the baby’s consanguinity: “the child is essentially produced from the blood and stamina of the father only, and that the several femes only supply the Foetus”. Although Robinson had been named Chief Justice of Gibraltar in 1740, he never took up the post, and this significantly delayed the setting up of law courts in Gibraltar. The book includes a plate outlining the degrees of consanguinity.

Women in the law: female lawyers

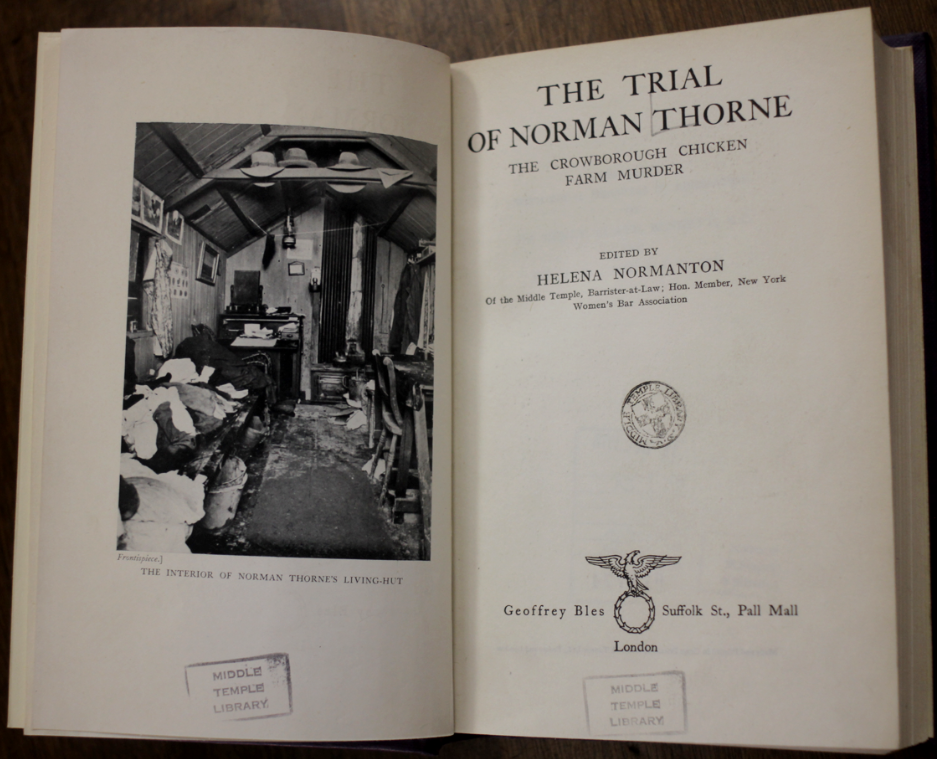

In addition to being the first woman to be admitted to an Inn of Court, the second woman to be Called to the Bar, and the first to practise as a barrister in England, Helena Normanton was an early advocate for women’s rights. In 1914 she published a pamphlet entitled Sex differentiation in salary, which argued for equal pay for equal work. Throughout 1919 she was a speaker at many Women’s Freedom League meetings. In April 1919 Normanton argued that “all branches of the legal profession should be opened to women” at a debate meeting of the Union Society held on ‘Ladies Night’ at Lincoln’s Inn

Normanton supplemented the income from her legal practice with public speaking engagements, writing articles for publications such as Good Housekeeping and editing trial accounts for the Notable British Trials series. This was most likely due to the low income she was receiving working as a barrister, which was the result of discrimination at the Bar and less support for female barristers.

Normanton supplemented the income from her legal practice with public speaking engagements, writing articles for publications such as Good Housekeeping and editing trial accounts for the Notable British Trials series. This was most likely due to the low income she was receiving working as a barrister, which was the result of discrimination at the Bar and less support for female barristers.

The trial of Norman Thorne: the Crowborough chicken farm murder, 1929.

Thorne was a Sunday school teacher and chicken farmer convicted of murdering his fiancée, Elsie Cameron. Although they were engaged, Thorne soon lost interest when he met another young lady, Bessie Coldicott. While she was on a weekend visit to his farm in Crowborough, Thorne killed Elsie, dismembered her body, and buried the pieces around his farm.

Thorne claimed she committed suicide, but at the trial the pathologist, Sir Bernard Spilsbury, was able to show that this was impossible, as no marks were left on the beams from which she supposedly hung herself.Helena Normanton wrote a poignant introduction to the trial, reminding the reader of the victim’s distressing vulnerability.

Trial of Alfred Arthur Rouse, 1931.

Trial of Alfred Arthur Rouse, 1931.

Rouse was convicted of killing an unknown man whose identity was never established. Rouse had been severely disabled in the war, suffering a knee and head injury. Rouse told police that he had travelled overnight to Leicester in his car, taking on a hitchhiker who managed to set himself alight in Rouse’s car when Rouse went into a field to relieve himself. Police believed that Rouse was attempting to disappear by using the unfortunate and unknown man as a stand-in body. Rouse had fathered several illegitimate children, with no way to maintain them on his travelling salesman’s salary. Normanton’s view was that “Rouse deliberately arranged the body of his victim so as to obtain the maximum amount of combustion possible”. The Rouse case is well-known for one of the questions asked during cross-examination: “What is the coefficient of the expansion of brass?” It serves as an example of an expert witness “being painted into a corner”, cross-examination being largely irrelevant, and the duty of the courts to ensure that witnesses are treated fairly: see 1997 M.L.J.I. 3.

In preparing this text, Normanton received help from Morris Motor Cars. A member of staff there “of similar dimensions to the burnt man, [demonstrated] in a car of similar construction to the one Rouse used, the facts narrated in the confession. This was most helpful and convincing”.

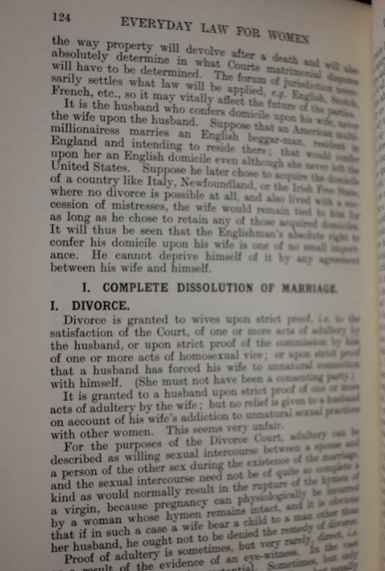

Everyday law for women, 1932.

Everyday law for women, 1932.

This work continues the tradition of books that explain the law to women in less technical terms than those required of a practising lawyer. Normanton aimed to take “an English female creature in her journey from cradle to grave upon a sort of aerial voyage of the terrain of her country’s laws, so far as they are most likely to affect her”. One 1934 reviewer accused Normanton of over-emphasising “on detail”, which he* deemed unnecessary and undesirable “in the sections dealing with unhappy marriages and with sexual relationships and crimes generally”. It is unclear why detail would be unnecessary or undesirable, however.

is in the preface of this work where Normanton explains that her ambition to become a barrister started when she was twelve.

*The author of the review is given simply as M.G.C.

As Wilfrid Prest has pointed out, women did work in the legal profession prior to Normanton’s Christmas Eve 1919 admission to Middle Temple. Women worked as clerks (Maria Rye set up a stationer’s business in 1859) and there is evidence of two women opening a “legal office in Chancery Lane” in the 1880s. Even earlier than that, however, Nehemiah Grew (1641-1712) wrote an unpublished treatise (MSS Lansdowne 691 and Huntington HM 1264) in which he lists “some women” attorneys, including “one Hawkins, a female solicitor … said to be known to most of the judges” who was practicing during the late 17th/early 18th century. Unfortunately Mistress Hawkins remains unidentified. Margaret Brent received authority to act as attorney on 3 January 1648 from the Maryland Assembly, making her the first woman to practise law in the English colonies of what later became the United States of America.

Other firsts for women in the law were:

1888: Eliza Orme became the first woman to earn a law degree in England at University College London;

1903: Bertha Cave applied unsuccessfully to be admitted to Gray’s Inn;

1919: Ada Summers became the first female magistrate;

1920: Madge Easton Anderson became the first female solicitor in the United Kingdom;

1922: Ivy Williams became the first woman to be Called to the Bar in England and Wales.

Although women were not admitted to the Middle Temple as students until 1919, they did of course contribute to life at the Inns prior to this, in particular as shopkeepers and employees. This 1755 example from the Archive (MT.1/PPA) is a petition from Elizabeth, widow of John Martin, late Chief Porter. Mrs. Martin asks the Benchers to continue to allow her to gown the members, disputing the idea that this is the sole preserve of the Chief Porter. She shows that in 1712 one Mrs. Robins, a ‘trencher scraper’ in the Hall had enjoyed the benefit of gowning the gentlemen “for many years” and continued to do so until her death in 1738. Mrs. Martin had bought her gowns from Mrs. Robins’ husband and continued to gown gentlemen until 1753, when she joined in partnership with George Wood, the Butler. Throughout this time the Chief Porter did not gown the gentlemen. At the Parliament held in May 1755, Mrs. Martin’s petition was granted and she was allowed to continue gowning the barristers.

Widows are also mentioned throughout the Minutes of Parliament. These include Florence Bellows, who had tenure of a house adjoining the gate of the Inn “on the right” in 1579. In 1607 ‘Widow Carter’ is told to “pull down” the house built by her late husband, William Carter, on the west side of Temple Lane. She was allowed to make a profit from the materials and is given £10 by the Treasury. However, by 1611 she was still in the house!

Widow Gregorie (Gregory) was a tenant in possession of a spectacle shop “without the gate, west side” in 1634, and was granted an extension of her lease for seven years.

Women worked at the Inn as employees as well. In 1673 the ‘house laundress’ was given five marks “because of the dearness of coals”. In 1687 Widow Smith petitioned the Inn for “her service in the buttery and scraping trenchers for a year past”. She is finally given five marks for her service at the Parliament of 14 June 1689! In 1702 they gave Widow Ule, the cleaner of the Parliament Chamber and Library, 40s “to relieve her in a long sickness”

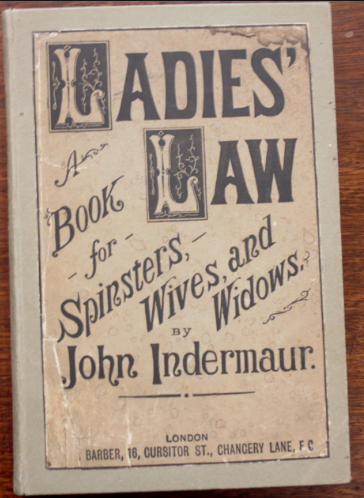

John Indermaur, Ladies’ law

When John Indermaur, Ladies’ law: a book for spinsters, wives and widows [circa 1886] was published, it cost 1 shilling and 2 pence, according to an 1887 advertisement in The Standard.

The book is intended for the lay-woman, not the “dry lawyer” and is intended to “furnish you [i.e. women in general] with information on your own affairs”. The author is careful not to “shock” the reader with “objectionable criminal details”. Despite the somewhat patronising introduction, the author seems to be seriously trying to address the fact that women’s legal rights were changing rapidly at this time and that women had not had recourse to reliable texts outlining their legal rights.

Indermuir writes: “I shall show you your rights and position as a spinster, a married woman, and a widow” and will “strive to shew you your legal position both as regards us [i.e. men], and contrasted with us”. Spinster in Indermuir’s text refers to women before they are married: not as young girls, but as women in the early stages of life. Indermuir points out the injustice that “males are preferred to females” with regards to freehold property and its inheritance, but avers that this unequal situation “will not last much longer”.

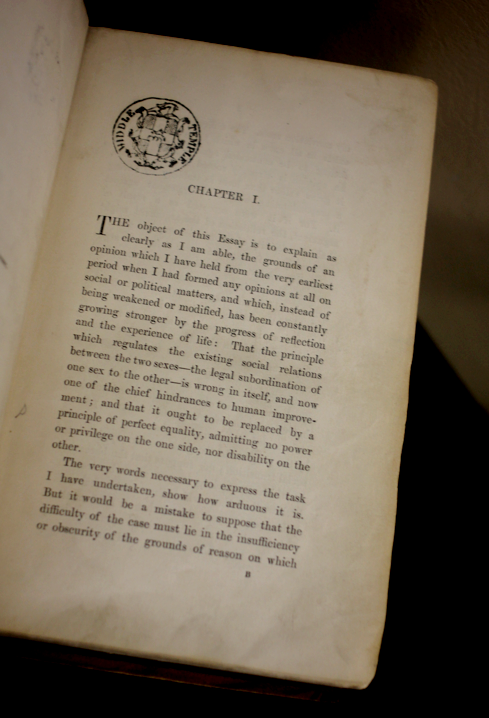

John Stuart Mill, The subjection of women, 1869

John Stuart Mill, The subjection of women, 1869

This is the second edition of Mill’s famous and popular work on women’s rights. It is well established that Harriet Stuart Mill, John’s wife, contributed in various important ways to it, including contributing to the “practical bearings of women’s disabilities” and that “women's freedom was 'the great question of the coming time: the most urgent interest of human progress'”. In addition, Mill himself says that its conception was due to his step-daughter Helen, and was “enriched” with her important ideas. The work also “drew on the arguments for women’s enfranchisement set out by Harriet in her July 1851 article in the Westminster Review. The critique of views that afforded women superior moral status as a compensatory placebo for inferior legal power directly echoed Harriet's curt dismissal of these visions of women as a 'sentimental priesthood'”.

The book references court cases which dealt with the violence meted out by men on their wives and servants. John and Harriet Stuart Mill had written about these atrocities in articles published in The Morning Chronicle – two such cases occurred only three days apart (26 and 29 March 1850). The first was that of Mary Ann Parsons, a fifteen-year-old girl, who was beaten to death by either one or both of her employers, Courtis and Sarah Bird. The couple were

blow, or who inflicted the fatal blow. The Stuart Mills point out that, had the victim been a man the “assassins … would not be suffered to escape because no one could swear that the particular wounds inflicted by them were the mortal ones”.

The second case was that of Susan Moir, who was beaten to death by her husband Alexander Moir. At the trial, ample evidence was given of the fierce beatings he gave his wife prior to her death. The surgeon who performed the post-mortem examination of Mrs. Moir described her head as being “in a perfectly pulpy state”. Moir was found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to transportation, but his sentence was converted to imprisonment.

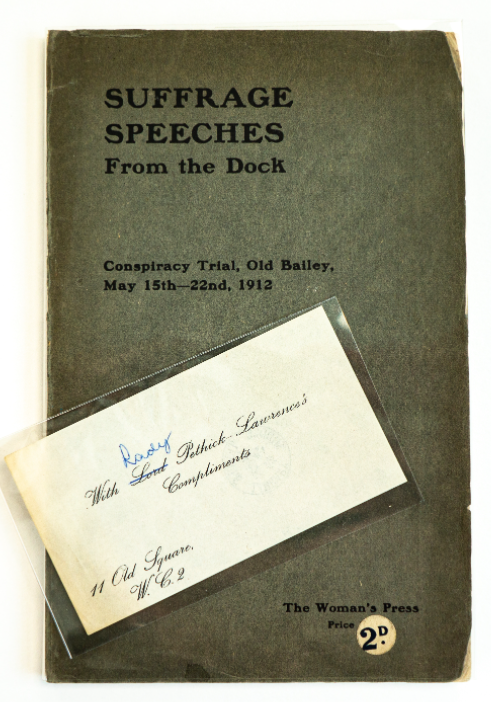

Suffrage Speeches from the Dock

Made at the Conspiracy Trial, Old Bailey, May 15th-22nd, 1912. This slim booklet reproduces Mr. Pethick Lawrence's opening address to the jury, Emily Pankhurst's defence, Mr. Pethick Lawrence'sdefence, Mr. T. Healy’s speech as the counsel for the defence, and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence's appeal to the judge. The Middle Temple Library copy includes Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence’s compliments slip, with 'Lord' crossed out by hand and replaced with 'Lady' to repurpose her husband's card.

Printing the Law

Research on women printers in the 16th to 18th centuries has brought a hidden aspect of women’s work to light: according to Maureen Bell, over “300 women [have been] identified as connected with the [book] trade between 1557 and 1700.” Women often co-managed the printing businesses with their husbands and continued managing the business on their own after their husband’s death. Their names can be difficult to track down however, due to the use of ‘widow’ and initials rather than full names on title pages.

Elisabeth Pickering, widow of Robert Redman, was probably the earliest female printer of law books in England, and the earliest to print using her maiden name. After Redman’s death, Elisabeth married William Cholmeley, at which point she sold the printing business to William Middleton. After William Cholmeley’s death, she married Ranulph Cholmeley, who later became Chief Justice of the Common Pleas. In 1541, Elisabeth printed The great Charter called in Latyn Magna Carta. As Ranulph was not a Freeman of the City of London, once they were married Elisabeth was no longer able to be a member of the Stationers’ Company in her own right. In 1551 the Company wanted to become incorporated and employed Cholmeley to act as their lawyer. Incorporation would allow the Company to extend the jurisdiction of their book trade beyond London. It is believed that Elisabeth assisted Ranulph with his work on the Stationers’ incorporation. Elisabeth died in 1562 and was buried in St. Dunstan-in-the-West.

One of the earliest female printers managing a 16th century printing press in London was Jane Yetsweirt, who inherited the press from her husband Charles in 1595. Charles had a patent for the printing of law texts which was passed onto Jane. These patents were lucrative exclusivity agreements with the Stationers’ Company; printing law texts was one of the more lucrative of the contracts. Jane consistently had to fight with the Company to retain her rights, however, with the Earl of Essex writing to various dignitaries on her behalf. She continued to print until her death in 1597.

In 1594, Charles Yetsweirt published Of the interchangeable course, or a variety of things in the whole world, a translation of Louis Leroy’s De la vicissitude ou variete des choses en l'univers made by Robert Ashley, this library’s founder. The book contains a detailed passage on the history and technology of printing itself. Yetsweirt’s print shop was located on Fleet Street, near to Middle Temple Gate.

Elizabeth Flesher inherited a printing business from her husband James Flesher, and printed several legal works, including John Fortescue’s De laudibus legum Angliae in 1672. The English Short Title Catalogue lists over 30 law books printed by ‘E.’ or ‘Eliz.’ Flesher. She also printed theological works and books by Robert Boyle.

Elizabeth Nutt started printing in 1716, eventually entering into partnership with Robert Gosling and others from 1717 to the 1730s. She printed several legal works, including Matthew Hale’s The History of the Common Law issued posthumously in 1716 and Blount’s Law Dictionary in 1717.

Notable British Trials – Sally Smith QC

In 1905 Mr Harry Hodge, a court reporter in an Edinburgh law publishing firm run by his father (William Hodge and Company) began this series as a hobby to inform ordinary members of the public about what really went on in the solemn trials of the sensational crimes they read about in the newspapers.

The format was intended to appeal to the scholarly interests of “the lawyer, historian and medical man” whilst still engaging “that wide range of society called the General Public”. None of the sensation and human interest was to be lost; neither was the intellectual rigour of the solemn application of the rules of evidence to the facts of the case.

To encompass both, the books consisted of an introduction tracing the history of the case written by a guest editor, all well known in their day, a verbatim transcript of the legal proceedings, encompassing the appeal if there had been one, and an appendix containing a selection of other informative trial exhibits.

The series proved a raging success, not least because of the marked literary merit of the introductions. Armchair detectives, amateur criminologists and those who just wanted to read a good story all revelled in it. Each volume covered a notable trial from 1586 to 1953. After the series ceased in 1959, it attracted a cult following of collectors eager to amass an entire set. There were 83 volumes.

Fifty-eight years later in 2017 a publishing firm called Mango Books licenced the Notable British Trial imprint and triumphantly brought out the 84th volume, impeccably produced with the same format and distinctive cover of its predecessors. More have followed and still more are planned for the future.

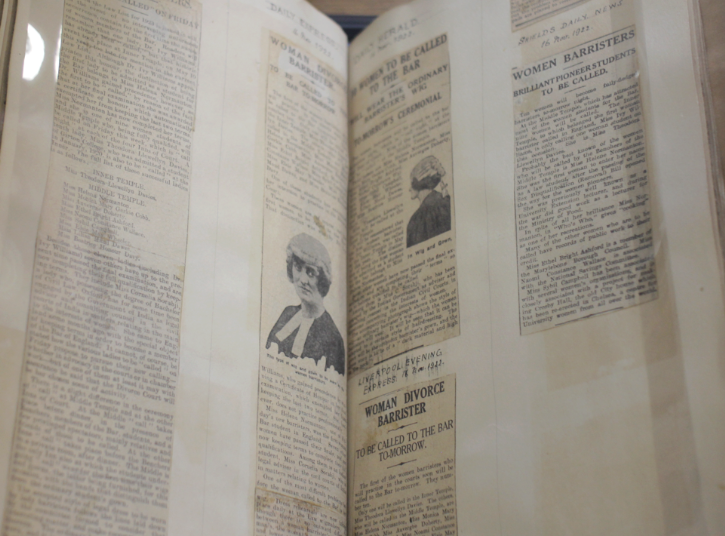

In the News

Newspapers such as The Times and the Illustrated London News erroneously named Olive Clapham (admitted Middle Temple 17 January 1920, called 17 November 1924) as the first British woman barrister. She was in fact the first woman to pass the English Bar examinations. According to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography:

“In May 1921 [Ms. Clapham] became the first woman to pass the bar finals examinations, placed in the third class. This achievement received some press attention, and several newspapers erroneously described her as the first woman barrister (The Times, 26 May 1921). In fact, twelve dining terms—four a year—also had to be kept before a person became eligible for call to the bar. Clapham had kept six terms, so she had eighteen months of dining still to complete. Meanwhile, Ivy Williams was excused two terms’ dining in recognition of her first-class pass and was the first woman called to the bar, on 10 May 1922.”

The scrapbook above from the Archive (MT/19/SCR/7 - 'Vol. D - Women Barristers') shows a newspaper clipping from the Daily Herald, 16 November 1922 announcing the Call to the Bar of nine women, who were all being Called at Middle Temple. Ivy Williams had been Called at Inner Temple in May. This clipping also shows the style of barrister’s wig, which “can be altered to a certain style of hairdressing”. Presumably this was to reassure its readers that the wig would not impede any fashionable 1920s bobs that the ‘lady’ barristers may have been keen to show off.

The Women in Law exhibition was held from January to April 2022, curated by Renae Satterley, with contributions from the Middle Temple Archives and Dr. Gillian Murphy.

Displayed Items

John Aylmer, An harborovve for faithfull and trevve subiectes, agaynst the late blowne Blaste, 1559

John Fortescue, De laudibus legum Angliae, 1672

John Indermaur, Ladies’ law: a book for spinsters, wives and widows [circa 1886]

Inner Temple, Report of the committee appointed to obtain information and to report on the admission of women as advocates in the courts of countries other than the United Kingdom, 1919

John Stuart Mill, The subjection of women, 1869

Helena Normanton, The trial of Norman Thorne, 1929 and Trial of Alfred Arthur Rouse, 1931

Helena Normanton, Everyday law for women, 1932

Edmund Plowden, Abridgment des touts les cases reportez, [circa 1597]

A treatise of feme coverts: or, the lady’s law, 1732

Robert Robinson, A discourse concerning the law of inheritances, 1736

Suffrage Speeches from the Dock. Made at the Conspiracy Trial, Old Bailey, May 15th-22nd, 1912

Rice Vaughan, Practica Walliae, 1672

John Webster, Vittoria Corombona, or, The white devil. A tragedy, 1672