The Middle Temple has been situated in its current position for around seven centuries. During this time, however, it has witnessed vast changes to its surrounding environment, including to the River Thames, on the bank of which it directly sat for the majority of this time period. The tidal river has substantially altered in character, being wide, meandering and slow moving in the medieval period prior to several different embanking works that narrowed the river, deepening and increasing the flow of the water and making it easier for ships to navigate. There were several embanking projects that directly impacted the Temple. The embanking projects of the 1530s and in 1770 benefitted the Inns by granting them more land for their gardens and the building of additional chambers, but the largest and most significant project for those on the north bank of the river, the creation of the Victoria Embankment in the 1860s, had the potential to be detrimental to the Inn and deprive it of ancient property rights.

Plan of Middle Temple Garden, showing the land added to the Middle Temple through the 1770 embanking works, 30 October 1839 (Plan/2/E/1)

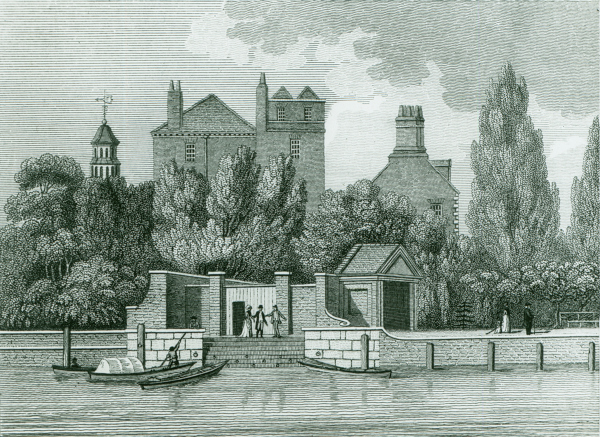

Prior to the creation of the Victoria Embankment, the gardens of both the Middle and Inner Temple directly fronted the river. Direct access to the river had been one of the attractions of the site for the first fourteenth century lawyers who had come together to form the Society, the Thames being one of the main means of navigation through what is now Greater London and providing easy access to the courts at Westminster. Middle Temple owned a pier, known as the Temple Stairs, which was used by London’s watermen to ply their trade and ferry passengers and goods up and down the river to and from the Inn. Fronting the river was a brick wall with several piles sunk into the riverbed in front of it, protecting the wall from boats and barges. These craft, the mooring of which was an ongoing source of frustration to the Benchers, had damaged and collapsed the wall in 1772.

Print of Temple Stairs south of Temple Gardens, prior to the creation of the Victoria Embankment, 1801 (MT/19/ILL/D/D8/4)

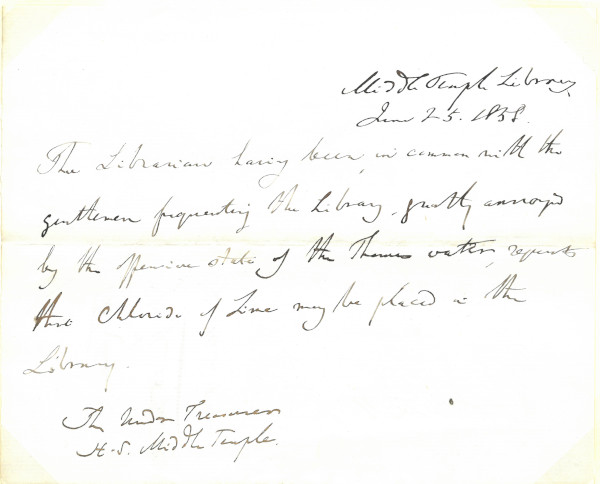

In the nineteenth century, additional embanking works became seen as highly desirable by the residents of London. From 1811 to 1851 the industrial revolution had caused an explosion in the population, doubling it to just under two and a half million. It is estimated that over 200,000 entered the city on foot every day, and further tens of thousands by steamboat, omnibus and railway. This placed a huge amount of pressure on London’s roads and public transportation, with the route between the City of London and Westminster through Temple Bar being a particular bottleneck. Additionally, the state of the River Thames had become deplorable beyond modern imagination due to the expansion in population, banning of unsanitary cesspits and the invention of the domestic flush toilet diverting large quantities of sewage into the Thames. Industrial waste was also dumped straight into the water, creating a disgustingly polluted river, and terrifying a population that still believed that disease was spread through bad odours. This noxious combination of pollutants culminated in the ‘Great Stink’ of summer 1858, which made living in the city almost unbearable. A letter from the Middle Temple Librarian to the Under Treasurer written on 25 June 1858 reads ‘The Librarian having been, in common with the gentlemen frequenting the Library, greatly annoyed by the offensive state of the Thames water, requests that chloride of lime may be placed in the Library’. Lime chloride was used during this environmental emergency to try and reduce the offensive smell, to little effect.

Letter from the Librarian to the Under Treasurer, requesting lime chloride to alleviate the smell in the Library during the 'Great Stink', 25 June 1858 (MT/2/TUT/123)

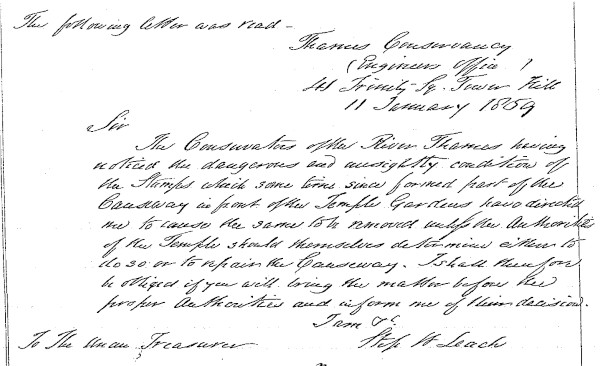

Prior to the commencement of building work on the Embankment in 1864, interim measures were taken to try and improve the condition of the river. In 1857, the Thames Conservancy was created, its existence made possible through the Thames Conservancy Act 1857, which allowed the Corporation of the City of London to take ownership of the river. Responsibility for the Thames was given to the new body and they soon began to exercise their authority over the Middle Temple, writing to the Under Treasurer on 11 January 1859 to complain that ‘The Conservators of the River Thames having noticed the dangerous and unsightly condition of the stumps which some time since formed part of the causeway in front of the Temple Gardens have directed me to cause the same to be removed unless the authorities of the Temple should themselves determine to do so or to repair the Causeway.’

Copy of a letter from the Thames Conservancy regarding the repair of the causeway in front of Temple Gardens, 11 January 1859 (MT/1/MPA/15)

This was not the Inn’s only run-in with the Conservators. Due to the tidal nature of the Thames, when the river was at low tide large mud flats were exposed in front of it on which foul silt, animal and vegetable refuse, dead animals and other noxious materials were left to bake in the sun. The Society had seen a general improvement in the state of the mud after the removal of Essex Pier to the west of the garden, but the riverbed was still in a terrible state. In 1860, the Thames Conservancy made proposals to improve the muddy state of the river in front of Middle Temple, raising the height of the riverbed in front of the garden using gravel ‘or some other suitable substance’. The Society, seeing the merit of these proposals, adopted them.

Ground plan of a proposed new landing place at the Middle Temple showing the mud on the foreshore at low tide, nd (Plan/3/A/6)

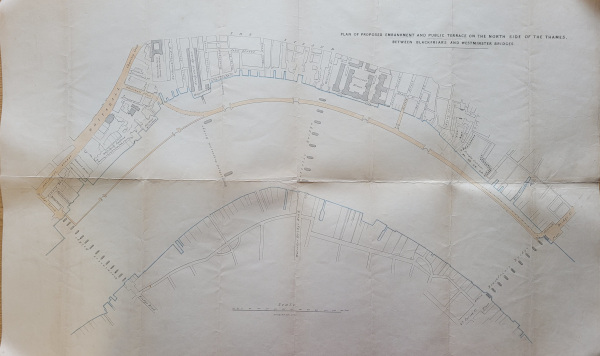

The Embankment project was intended to provide many different benefits to London. One of these benefits was to eliminate the ‘miasmatic’ mud banks, and it would also have the advantage of providing new land for an intercepting sewer in front of the river, which would have large benefits for the health of the city. The Embankment would also create space for a new roadway and railway that would help to reduce the traffic, which had grown exponentially with the booming population of the city. An additional benefit was the beautification of the river front that was in the 1850s marred with ‘dirty wharves, stinking dust-yards, fever-pools, and an open-air brewery of every form of zymotic disease’.

Plan of proposed Embankment and public terrace on the north side of the Thames, 1857 (MT/5/TSE/16)

Parliament passed the first Thames Embankment Act in 1862, after several years of procrastination, followed by others in 1863 and 1868. These granted permission for the construction of the Victoria Embankment on the north side of the Thames and the Albert Embankment on the south side. The creation of the accompanying roadway had the unfortunate effect of cutting the Middle Temple and Inner Temple off from their direct river frontage and their traditional rights of access via Temple Stairs. Together the Inns petitioned the House of Lords and the House of Commons in 1864, as they considered that the loss of their immediate access to the Thames and the creation of a public highway would be seriously prejudicial to them. Not only would it destroy their privacy but also interfere with their rights to the soil and bed of the Thames and would consequently decrease the property value of the Temple.

Plan of the Thames Embankment showing the property lines of the Middle Temple and the Inner Temple running into the River Thames, c.1860-c.1870

In addition to these concerns, a new railway, known as the Metropolitan District Railway, was also planned to pass under the new Embankment and there were worries about the noise, smell and vibrations created by this underground steam railway. Benchers were extremely concerned about these additional sources of pollution when they were already overwhelmed by the stench of the river and the nearby gasworks. In order to address these concerns, the two Inns appointed the engineer Charles Gregory to advise them on the effects of the proposed schemes on the Temple. Gregory wrote to their solicitors on 13 May 1864 about various issues, including the potential of vibrations to affect the south end of Kings Bench Walk, as the proposed railway route was only 105 ft. away from these buildings. He concluded that the buildings were unlikely to be affected but suggested that the Inns should ensure that the Railway would be held responsible in the event of damage. He also thought that noise would not be an issue and that the amenities of the garden would not be negatively affected by additional smells or noise pollution.

Report of Charles Gregory, Civil Engineer, on the impact proposed works by the Metropolitan District Railways on the Temple, 13 May 1864 (MT/21/1/12/4/2)

After much discussion, the Middle Temple and Inner Temple came to an arrangement with the Metropolitan District Railway Company and Articles of Agreement were drawn up in 1864. The railway was allowed on Temple Grounds only in a tunnel or covered way and there were many conditions laid down about the manner of its construction. It took many years for terms to be finalised and the railway company, under significant pressure to complete their new line from Westminster to Blackfriars, came to a final agreement with the two Inns on 6 November 1869 and granted them a joint compensation package of £5000. In return the two societies granted a perpetual easement to the railway company for making, maintaining, repairing and using the railway, under the condition that they had six months from 8 November 1869 to complete the building works. The railway was opened to the public on 30 May 1870 and within six weeks the Embankment carriageway was laid down. The Victoria Embankment was at last opened ceremonially by the Prince of Wales and the Princess Louise on 13 July 1870.

Wood engraving of the progress of the Thames Embankment works at Temple Gardens, 4 February 1865 (MT/19/ILL/D/D8/9)

Despite the loss of direct access to the river via the garden, the Inns were keen to retain their traditional rights of access. There were strenuous objections be the Benchers when they realised that proposals for the Embankment involved reducing the width of the river opposite the Temple by more than 100 yards and devoting part of the land to the construction of a line of docks. It was feared that this would eventually destroy their right of access to the Thames from Temple Gardens. A compromise was reached and Section 30 was inserted into the Thames Embankment Act 1862, reading:

‘The Board may and shall make for the Two Societies a Landing Place, with proper and sufficient Works and Conveniences connected therewith, in substitution for their current Landing Place at the End of Middle Temple Lane, and the same shall be used by the Inner Temple and the Middle Temple, and shall be held, enjoyed and regulated by the two Societies as their private Landing Place accordingly’

Reproduction photograph of the Victoria Embankment and Temple Pier, 1895 (MT/19/ILL/D/D8/22)

A special pier was constructed, marked with the arms of the Middle Temple and the Inner Temple, near where the Temple Stairs once stood. Despite the battle over the rights of the two Societies to the river, it appears that their rights of access became forgotten and unexercised for half a century. The pier was used in 1924 for three chartered steamers to take the Inns of Court Mission, a mission for working men and boys on Drury Lane, on an outing. It was used again for a trip by members in 1934 with the exclusive purpose of asserting ‘the exclusive right of members of the Inns to use the Temple landing-stage, at which no boat has touched for many a long day’ and further outings were planned in later years to reassert the Temple’s rights to the river.

Members of the Middle Temple and the Inner Temple at the Temple Landing Stage waiting to embark on a boat trip, 21 July 1934 (MT/7/EVE/20)

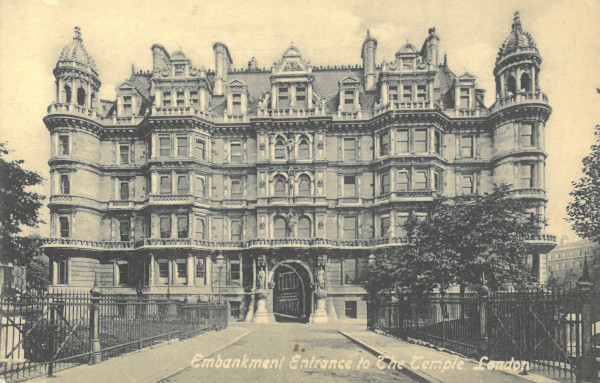

Despite the Embankment opening in 1870, the new Temple Entrance into Middle Temple Lane from the new public road was only completed in 1880 as there was some debate over the desirability of the lane joining the new roadway. On 3 July 1868, a motion was brought for a new entrance to be create with a gate and porter’s lodge, but the Benchers voted against the motion, perhaps worried about the loss of privacy that was such a concern when the Embankment was in the early stages of design and construction. It was not until 1879 that the Benchers felt a road to be desirable and they approached the Inner Temple for their agreement to the project. The roadway was completed and a new lodge for the use of a porter in attendance at the gate was erected on the Middle Temple side of the lane.

Postcard of the Embankment entrance to the Temple, late nineteenth-early twentieth century (MT/19/ILL/E/E8/2)

The Victoria Embankment has had a great impact on the Middle Temple, in one respect due to the alteration of its riverside character. While it still has access to Temple Pier, these rights are largely forgotten and unexercised. Fears of loss of privacy were also justified, with increasing through traffic causing the Society to shut its gates at various points in the twentieth century, much to public consternation. Nevertheless, the Embankment has also contributed to cleaner air and better health at the Inn, as well as playing a role in the gradual alteration in the use of chambers from dwelling places to offices by drastically improving transportation links and allowing barristers to live further afield. Despite concerns about the changes brought to the ancient site of the Middle Temple, the Victoria Embankment has provided many benefits to the membership in the century and a half since its construction.