During the first centuries after the creation of the Inns of Court they had the reputation of being the ‘Third University of England’ where students could obtain a rigorous and demanding legal education as well as instruction in gentlemanly manners and pursuits. However, the Inns of Court subsequently entered a deep decline as educational institutions that lasted from around the 1640s to the 1840s. During this period there was no formal teaching or qualification required for Call to the Bar beyond a statement of respectability, the payment of fees, being a member for a certain number of years, eating the requisite number of dinners in Hall and going through the motions of Exercises. For many early 19th century barristers, the state of legal education at this this time was a source of acute embarrassment, but by the great efforts of 19th century reformers, the Inns of Court were rescued from becoming anachronistic social clubs.

A view of Middle Temple Hall, 1830 (MT/19/ILL/D/D1/16)

The state of legal education at the Inns is well illustrated by Charles Dickens, admitted to the Middle Temple in 1839, who wrote a scathing commentary on qualification for Call to the Bar in his collection of essays The Uncommercial Traveller, stating that ‘… [qualification] is done, as everybody knows, by having a frayed old gown put on in a pantry by an old woman in a chronic state of St Anthony’s Fire and dropsy, and, so decorated, bolting a bad dinner in a party of four whereof each individual mistrusts the other three…’. The law student, when seeking an education at the Inns of Court, was left almost entirely to their own devices and, according to the Rt. Hon. Lord Brougham & Vaux, Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain (1830-1834), ‘it is extremely unfortunate because it gives an appearance very often of more ignorance to legal men than they really have… [but] even as practical lawyers they are left very much to pick up their law in the best way they can, without the great assistance of a teacher’.

Members taking Commons in Middle Temple Hall, c.1840 (MT/19/ILL/D/D2/3)

The general attitude of many senior members of the legal profession in the mid-19th century towards legal education could be characterised as ‘complacent apathy’. They would however soon be put ill at ease as the purpose and utility of the Inns of Court began to be questioned. By the 1840s demand for reform from within the Inns by more progressive members was growing and in 1845 the Middle Temple, led by Richard Bethell, later Lord Westbury, set up a committee to consider the provision of lectures in civil law and jurisprudence. By January 1846 the Inn was committed to appointing a Reader in these subjects and to making attendance at these lectures a prerequisite for Call to the Bar – these would be the first official lectures since the abolition of the practice of Reading around 1680. However, these new educational requirements were not universally required across the Inns, mostly due to resistance from Lincoln’s Inn, and educational reform foundered without the incentive of external scrutiny.

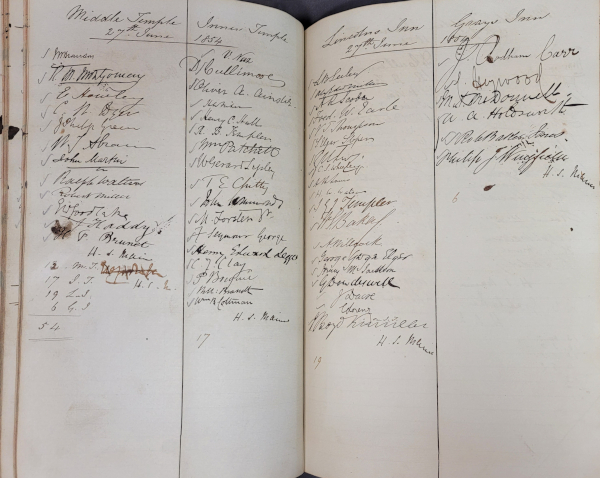

Attendance register for law lectures at the Inns of Court, 1846-1852 (MT/13/PPL/1/2)

The reformers, particularly Bethell, were not satisfied with this outcome and used their influence to push for further improvements. In 1846 there was talk of setting up a Parliamentary Select Committee to consider Irish legal education in Dublin and the radical politician Henry Warburton succeeded in widening its remit to encompass English legal education as well. The reformers made representations to the Committee, which were sympathetically received and it concluded that English legal education required urgent reform, being ‘extremely unsatisfactory and incomplete’ and ‘that no Legal Education, worthy of the name, of a public nature, is at this moment to be had in [England or Ireland]’. Recommendations made by the Committee included that a series of lectures be provided at all the Inns of Court and that those held at one Inn should be open to the members of all to attend. It also recommended instituting the creation of a Preliminary Examination prior to entry and a Qualifying Examination before Call to the Bar. The Commission also expressed the wish that the Inns of Court should form the basis of a ‘Legal University’ and that a joint body for dealing with matters of a common nature should be created.

Portrait of Richard Bethell, 1st Baron Westbury (1800-1873), legal reformer

As a result of the 1846 Parliamentary Select Committee, teaching appointments were made across the Inns of Court, but without central co-ordination any resulting improvements met with mixed results. The response to this evident need was the creation of the Council of Legal Education in 1852, which co-ordinated the provision of legal education across all four Inns creating common standards for the first time in their existence. Attendance at lectures at all four Inns was made compulsory unless the student took a voluntary examination, leading to the Inns of Court holding their first public examinations in 1853. But while the academic study of law was introduced, the comparative and philosophical study of the subject was left to universities, with the Inns focussing on the professional education of future barristers.

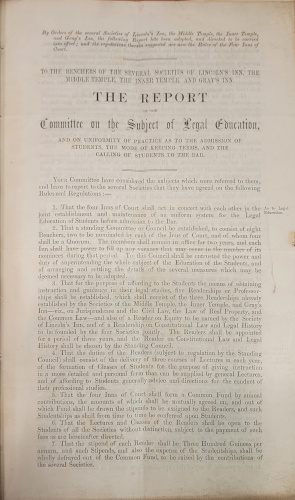

A Report of an Inter-Inn Committee making recommendations leading to the establishment of the Council of Legal Education, 1852 (MT/13/PRO/2)

The creation of the new Council of Legal Education and the institution of lectures and examinations represented some progress in improving education in England, but this was not enough for reformers and they demanded that the Inns of Court be further investigated for their neglect. This resulted in the creation of a Royal Commission to investigate the provision of legal education at the Inns of Court and Chancery in 1854. The Commissioners cast a highly critical eye over the provision of legal education at the Inns. They did not believe that a vocational education through undertaking pupillage, known at that time as ‘Reading in Chambers’ and being very informal in nature, sufficiently equipped students for a career in the law, nor eating dinners among other professionals. They also did not believe the new requirement for attendance at lectures would by itself add sufficient rigour to the training of barristers. In addition to the method of educational delivery being scrutinised, the funding allocated by the Inns towards legal education was thoroughly inspected.

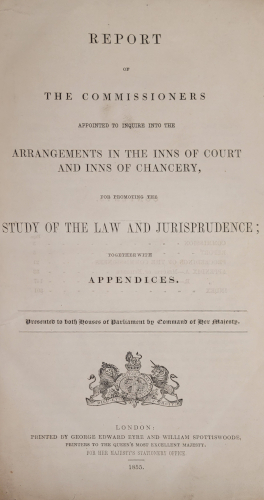

Report of the Commissioners appointed to inquire into the arrangements of the Inns of Court and the Inns of Chancery for promoting the study of the Law and Jurisprudence, 1855 (MT/13/MIS/4)

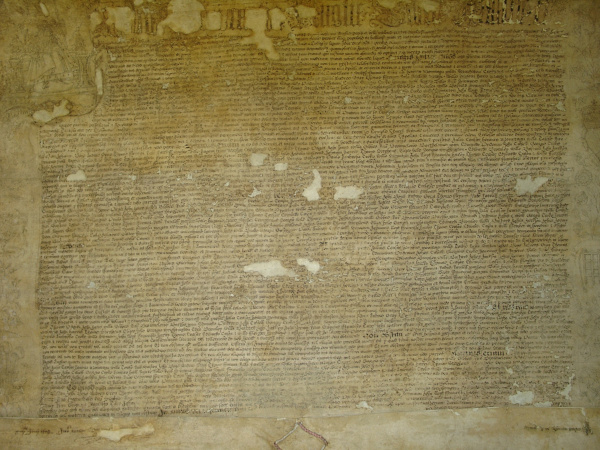

The Commission were under the impression that the Inns were hugely wealthy and had been diverting funds away from educational purposes – but there was some argument over the fiduciary or other duty of the Inns to provide an education at all. When it came to the Middle Temple and the Inner Temple, the argument was more clear-cut as the charter granting their lands to them by King James I stated that the lands ‘should serve for the accommodation and education of those studying and following the profession of the aforesaid laws, abiding the same Inns for all time to come’. However, some of the lands of the two Inns had been acquired after the grant of the charter and they were therefore not obliged to use the income from this property for educational purposes. In the end, the Commission founded the obligations of the Inn on two principles: ‘The Student is compelled to have recourse [to an Inn of Court] before he can practice at the Bar’ and a ‘duty which the Inns of Court owe to the community whilst conferring on individuals the right of practising at the Bar’.

King James I letters patent under the Great Seal to the Middle Temple and Inner Temple, 1608, granting them the lands of the Temple of the purpose of ‘accommodation and education’ of law professionals (MT/4/4)

After the duties of the Inns towards providing education were established, the Commission moved to examining their finances to see what could be diverted towards legal education. They found that there was no malfeasance within the Society and that there were was ‘credible instances of disinterestedness and public spirit displayed in the relinquishment of considerable fees heretofore payable to Benchers holding offices in the Inns’. The income generated by letting out chambers was highly scrutinised and they questioned Charles Whitehurst, Treasurer of the Middle Temple, on the matter. As part of the questioning the Commissioners investigated the possibility that chambers were being let out below market rate, but Whitehurst responded that chambers were so old and decayed that almost all of them must be pulled down. He argued that there were few funds for new educational initiatives because of the future need to spend large amounts of money rebuilding chambers and the Commissioners subsequently found that the Society lacked the ability to fund radical changes to legal education.

Photograph of Churchyard Court looking west showing the poor condition of the Middle Temple’s chambers, 1858 (MT/19/ILL/C/C3/39)

The Commissioners were disappointed in their search for money in the Inns’ finances to support educational reforms, but they did make recommendations that fell within their abilities at the time. In line with the previous recommendations of the 1846 Parliamentary Select Committee, they endorsed the creation of a Preliminary Examination for admission to the Inns of Court for students who had not undertaken a university degree, though there were a variety of opinions about the necessity for such an examination – the Inner Temple had already instituted a preliminary examination and found it very beneficial. However, some witnesses called by the Commission doubted its utility and one gentlemen even thought it could discourage applicants who would otherwise become ‘learned and useful Members of the Bar’. There was a similar diversity of opinion regarding a qualification examination prior to Call to the Bar, with the recently appointed Readers stating ‘the full benefit of Lectures will not be derived by any Student unless he knows that he is also to undergo an Examination upon the subject of them’ but that ‘this Examination should not be severe’. Other witnesses doubted the usefulness of such an examination, stating that ‘it would lead to the acquisition of only a very limited and superficial knowledge, and would be of no practical use’.

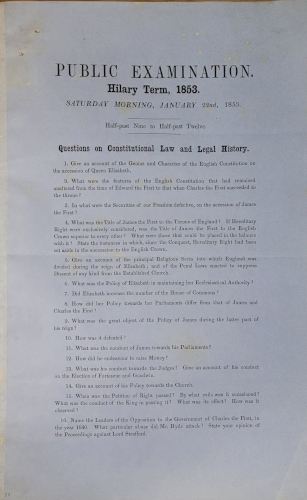

Public examination paper on Constitutional Law and Legal History, Hilary Term 1853 (MT/13/PRO/1)

The recommendations of the Commission ensured that the new Council of Legal Education was able to continue its efforts to standardise the quality of legal education at the Inns, though it was possible for a candidate for the Bar to avoid any examination in law until 1872. Even when examinations became compulsory, the questions were not demanding, providing a compromise to the more reactionary members of the Bar. During this period, the Council of Legal Education also expanded the education of British students to the study of the law of the Indian sub-continent, which was relevant to the administration of the newly established British Raj and would later serve as an attraction to international students from the Empire.

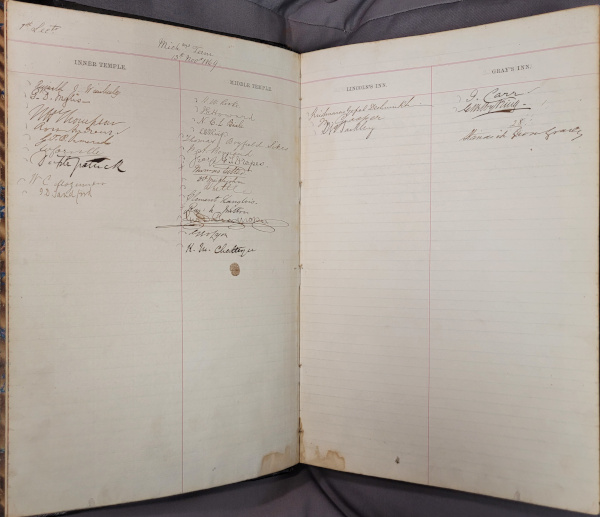

Hindu and Mohommedan law and the laws of India attendance register, 1869-1874 (MT/13/PPL/2/10)

Although there were some improvements made to the quality of legal education by reforms in the mid-19th century, the reformers of the time remained unsatisfied by the level of rigour demanded of candidates. The question of law education continued to be debated in Parliament, however despite the rhetoric in the House of Commons, which used quotations from the 1846 Select Committee Report to decry the state of the profession in the 1870s, there were substantial improvements made over three decades – the Inns of Court were collaborating together under the Council of Legal Education, lectures were regularly being given for the first time since the 17th century, compulsory examinations were instituted, and there were ‘convenient chambers’, ‘an excellent library’, ‘meals at convenient hours’ and ‘constant opportunities of intercourse’. The Middle Temple was well on track to becoming useful and relevant once again to the education of the prospective barrister.