Next to its grand Tudor Hall, the Middle Temple Garden is one of the most recognisable features of the Inn. Like the brick chambers that surround it, it has undergone a great deal of alteration over the centuries. These changes have been dictated by fashion, the practicalities of the environment and the changing landscape around the Temple, which have all changed substantially since the formation of the Society around the mid-14th century.

Photograph of the Middle Temple Garden, 1920 (MT/19/ILL/E/E11/17)

Little information exists about the Middle Temple Garden during the 14th-16th centuries, but it is certain that it was nothing like the garden that can be seen today. The current garden would have been almost entirely under water and there would have been comparatively little ground available for cultivation. The line of the medieval waterfront is thought to have been located near where the southern wall of the present Tudor Hall now stands, leaving very little space for a garden. In the 1530s, however, the land south of the Temple was drained to create more land for the growing Societies and the Middle Temple’s current garden was reclaimed from the Thames during this project.

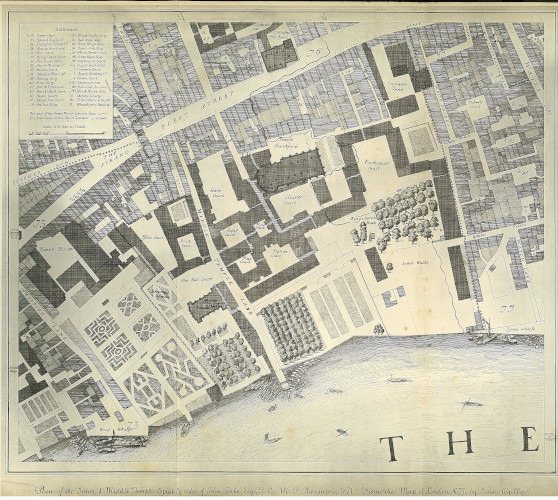

The earliest known surviving complete map of London, the Agas Map or Woodcut Map was created around the year 1561 and shows a little of the character of the Middle Temple Garden during this period. While Inner Temple Garden is shown full of large trees, and the lands to its western border that would later be occupied by Essex House demonstrate a more formal layout, the Society’s garden is shown to be bare. There may have been a grass lawn with various areas of planting, but this is difficult to ascertain from the limited detail in the cartographic representation.

Rough 19th century watercolour representation of the London Legal Quarter from the Agas Map, c.1561 (MT/6/PLA/1)

The earliest hard landscaping feature known about in the Middle Temple Garden was the enclosing wall. The Inner Temple’s Minutes of Parliament for 5 February 1534 reference a wall that had been built in their garden between the Thames and the embankment, probably following a reclaiming of the land, and in the 1540s further walls were erected to avoid the ‘displeasure, annoyance and disturbance of the gentlemen of the house’ from the ‘common recourse of all sorts of people into the House and garden by a door through the yard’. Unfortunately, the Middle Temple’s minutes from between 1525-1551 have not survived, but it is probable that similar measures were taken at the Inn around the same time. By the time the Agas Map was created, the garden is shown to be completely enclosed.

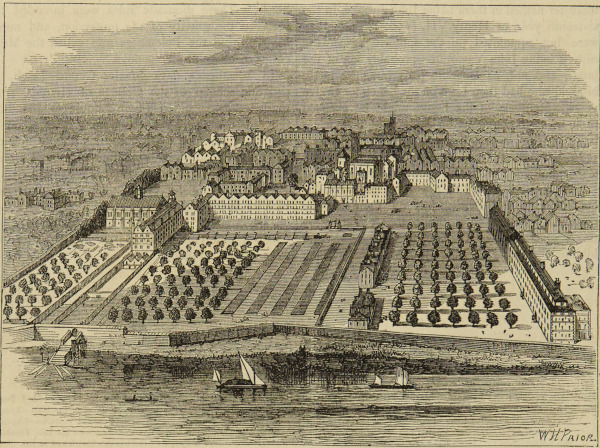

View of the Temple showing the enclosed Middle Temple Garden to the left, 1677 (MT/19/D/D8/2)

The Middle Temple Garden was not the only space dedicated to the cultivation of plants. There are references to a kitchen garden in the Minutes of Parliament dated 24 November 1609 and in bills from the late 1610s, which would have grown vegetables and herbs for culinary and medicinal use at the Inn. The minutes of 1609 reference a reduction in the size of the garden as it granted permission for Francis Warnett and John Puleston, members of the Society, to build a new set of chambers in the kitchen garden and this permission may have been granted due to a wider availability of produce in local markets than in earlier centuries. An estimated location of the garden can be ascertained by looking at the location of the newly built chamber, which was on Middle Temple Lane, and by the fact that it was ‘from the corner of the chamber of Mr Overbury northward towards the brick wall dividing the kitchen garden from the Town Buildings’. The name of the ‘Town Buildings’ may have been used by the author to refer to the buildings affronting Fleet Street. This would put the location of the garden near the modern Brick Court and John Ogilby’s map of London, produced in 1677, shows a small area of cultivation in a courtyard north of Brick Court. The position of this garden, some distance from the river, suggests the possibility that it predated the modern Middle Temple Garden.

Section of a map of London produced by John Ogilby showing the Temple, 1677

The first record of significant changes to the landscaping of the main Middle Temple Garden come from a series of bills produced in 1615. One bill is endorsed on the reverse ‘The gardener’s bill for the new knott in the Temple Garden’. Charges are recorded for ‘new making of the garden in the Benchers’ walk’, which is likely what subsequently became known as the Benchers’ Garden, situated where Fountain Court is today. The level of the ground was raised and, in keeping with the style of garden popular in the previous century, a formal geometric knot garden was created. Plants were purchased for hedging such as whitethorn, ivy, sweet briar and other native plants such as germander and pinks were obtained, as well as wire to bind rosemary. The plants that were chosen were highly scented, providing a relief from the smells of the urban environment, and this would have been thought to help prevent illness according to the medical theory of the time.

Gardener’s Bill listing plants acquired for the garden, 1618 (MT/2/TUT/3/13)

Banqueting houses, separate buildings reached through gardens and used for eating and entertainment, became popular during the 16th century. The Middle Temple had two of these houses and they may have been constructed around 1617 – a painter’s bill of this date records that he painted and gilded two little lions and painted ‘tow vaynes for the banqueting houses fitted into those tow lions’. A wild man stood on one of the banqueting houses and great lions stood upon the other. One of these banqueting houses was situated at the north-east corner of the Benchers’ Garden, which can be ascertained from the order of Edward Smyth, Treasurer, of 14 March 1682/3 that it be torn down ‘and lead from it and from the other banqueting house already pulled down, be sold…’

Order for the pulling down of the remaining banqueting house, 14 March 1683 (MT/6/RBW/23)

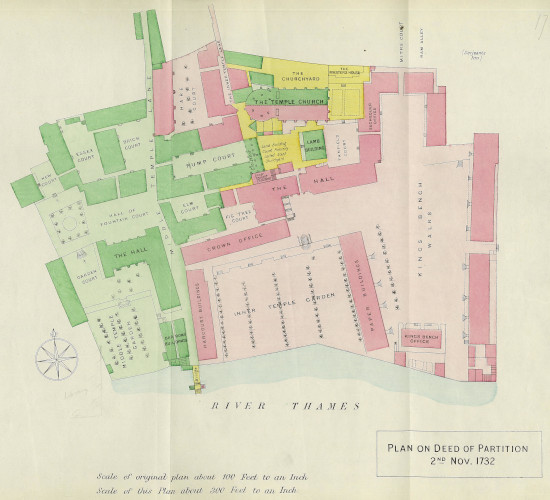

The Benchers’ Garden was destroyed to create Fountain Court when the Inn was rebuilt following the fire of 1679. Prior to this, the area outside Hall was called the Hall Court. The area that encompassed the Benchers’ Garden is the western part of the current Fountain Court. Ogilby’s 1677 map demonstrates the position of this old garden and shows that at this time the lower garden consisted of long avenues of trees, the ‘Lower Walks’ where the membership could promenade and engage in learned discourse. A plan dating to 1732 demonstrates the extent of the change in the Middle Temple’s landscape after the fire. The new fountain can be clearly seen on the plan and part of the Lower Walks became the newly created Garden Court.

Map included in the Deed of Partition between the Middle Temple and Inner Temple, 1732 (MT/4/5/1)

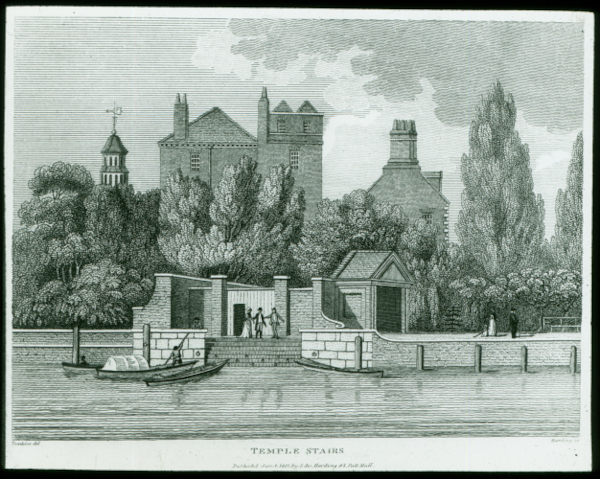

In the 1770s, the embankment of the Thames was extended in accordance with the Thames Embankment Act 1766. The purpose of the Act was to straighten the river bank for the purpose of preventing the accumulation of ‘malodorous silt’. As part of this project, Middle Temple Garden gained more land within its walls and the 16th century brick wall at the bottom of the garden was demolished and rebuilt at the new waterline. In 1772, the new wall collapsed and damaged boats that were moored along the bottom of the garden – this was blamed on boats mooring too close to the garden wall – and was subsequently rebuilt with greater protective measures installed. The embankment added a significant amount of land to the garden, including the area occupied by the current sundial and everything to its south.

View of Temple Stairs from the Thames showing the bottom of Middle Temple Garden on the left, 1801 (MT/19/ILL/D/D8/5)

In 1825 the centuries-long landscaping tradition of tree-lined walks at the Inn came under threat as the Benchers attempted to open the view from the recently completed Parliament Chamber, now the Queen’s Room, to the Thames by cutting down the lime-tree avenues. On 25 January 1825, the Inn’s Parliament ordered that it be authorised ‘to cut down the trees and improve the garden with all practicable speed’. The Sussex Advertiser, dated 7 February 1825 reported that ‘The well-known avenue of lime trees which has so long ornamented the garden of the Middle Temple, and which, during the summer, presented so pleasing a prospect from the river, has been consigned to the axe, by the absolute mandate of the Benchers, to the universal regret of the other members of the society. The reason assigned for this tasteless act of modern Vandalism is, that a few elderly gentlemen will, for a few years during Term time, have a less confined view of the river from the banqueting room which they have lately erected, for their own accommodation, at an immense expense out of the funds of the society’. On 14 March 1825 the following poem appeared in the London Telegraph:

Some sages hold this maxim most profound

“Who’s born to hang, need never fear being drown’d,”

Thus nought but water can old R****** please,

He courts the Thames, but dreads the sight of trees

The attempt was quashed by Parliament on 11 November 1825 under the strength of the opinion of the membership, but the traditional avenues of trees would not survive to the middle of the century.

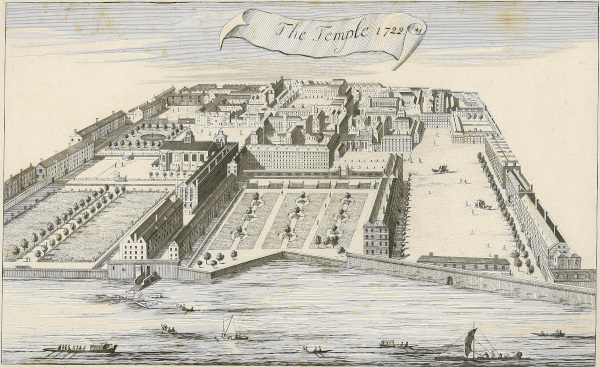

View of the Temple showing a long avenue of trees as the primary feature of Middle Temple Garden, 1722 (MT/19/ILL/D/D8/29)

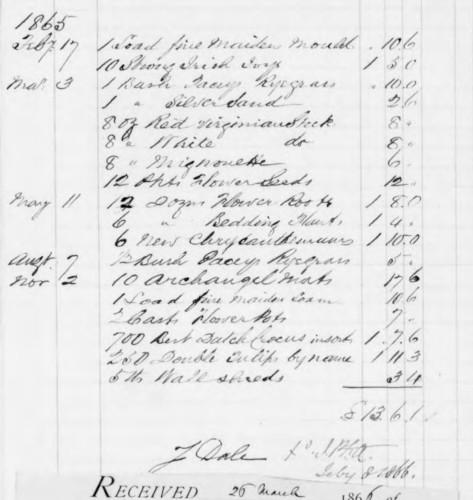

By the second half of the 19th century, the plants chosen for the Middle Temple Garden had changed significantly. A nurseryman’s bill from 1865 shows that many crocuses and tulips were purchased, as well as chrysanthemums, which were an import from east-Asia and gained widespread popularity in European metropolitan areas in the mid-19th century. The Temple had what may have been the largest collection of chrysanthemums in England at the time, consisting of around two hundred varieties, which flourished despite the polluted atmosphere of Victorian London. The Middle Temple opened their gardens to the public from 1853 to 1885 for public displays of the flowers. Pompon chrysanthemums were a particularly popular feature of the Middle Temple Garden shows and the Head Gardener Joseph Dale published a sixpenny manual on their cultivation ‘in or near large towns’, which suggested an arrangement of five rows of chrysanthemums in a twelve feet wide border with a row of pompon chrysanthemums in the front.

Nurseryman’s Bill showing varieties of plant in the Middle Temple Garden, 1865 (MT/2/TRB/229)

The polluted, smoggy atmosphere of Victorian London proved challenging for the Victorian gardener and at this time hardy plants were favoured. Samuel Broome, the Inner Temple Gardener, in his 1861 book Culture of the Chrysanthemum As Practised in The Temple Gardens, recommended the Christmas rose, snowdrops, the crocus, tulips and primrose, daffodils, narcissus, calceolaria, scarlet geraniums and balsam. He states that shrubs did not do very well at this polluted period in history, but recommended some that could withstand the atmosphere, as well as some varieties of dwarf roses, which, being close to the ground got less smoke on their stems. The Plane Tree was a particular recommendation as they shed their bark each spring ‘by so doing, it gets rid of the soot, which sticks to other trees like varnish, and which there is no getting off’. The only way in which he was able to obtain his show of chrysanthemums was to trench in six inches of dung and to subsoil the borders, burying the surface soot eighteen inches deep each year.

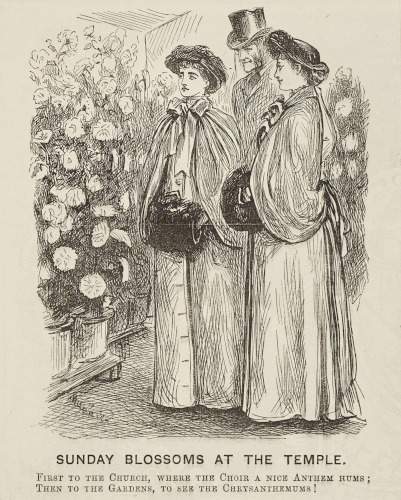

Print of two ladies and a gentleman viewing the Chrysanthemums at the Temple from Punch, 25 November 1882 (MT/19/ILL/E/E11/6)

Broome also recommended grass for the polluted atmosphere and in the late 19th and 20th centuries the Middle Temple Garden became prized for its lawn, which also featured tennis courts during this period. However, the condition of this grass was sacrificed for the war effort in both World Wars. Its condition was highly lamented in 1919 by the Halifax Evening Courier, which stated that it had been ‘justly appraised as the most delectable piece of greensward in London’, but that due to the Inns of Court Officer Training Corps drilling their volunteers, ‘The precious turf was churned into a greasy morass by hundreds of thousands of patriotic feet’. The turf was ruined again in the Second World War when the tennis courts were turned in to allotments and by the explosion of incendiaries in the garden.

Photograph of Middle Temple Garden showing the lawn to be its primary feature. The boundary of the tennis courts can be seen in the foreground, c.1920-c.1939 (MT/19/PHO/10/17/2)

The Middle Temple Garden has grown substantially over the centuries and seen many changes in its landscape and plants chosen for cultivation. With the improvement in London’s air quality since the passing of the Clean Air Act 1952, a wide array of plants can again be cultivated in the city and the Middle Temple Garden now has a verdant display of colour and texture alongside its famous lawn. Despite the changing environment, the garden has always provided tranquil oasis within the bustling city and will no doubt continue to do so for many centuries more.