This year we mark 450 years since the construction of Middle Temple Hall. The Hall has, since it was completed, played host to the Inn's established educational and collegiate activities, and served as the magnificent setting for some of the central events and rituals in our calendar such as the Reader's Feast and Call to the Bar. However, behind the dignified atmosphere, scholarly solemnity and grand ceremony, there is a rich tapestry of misbehaviour and rule-breaking in Hall on the part of students, members and guests - ranging from sartorial faux-pas to sword-fighting. This month, we trace this story from the era in which Hall was built to the present day.

Early Transgressions

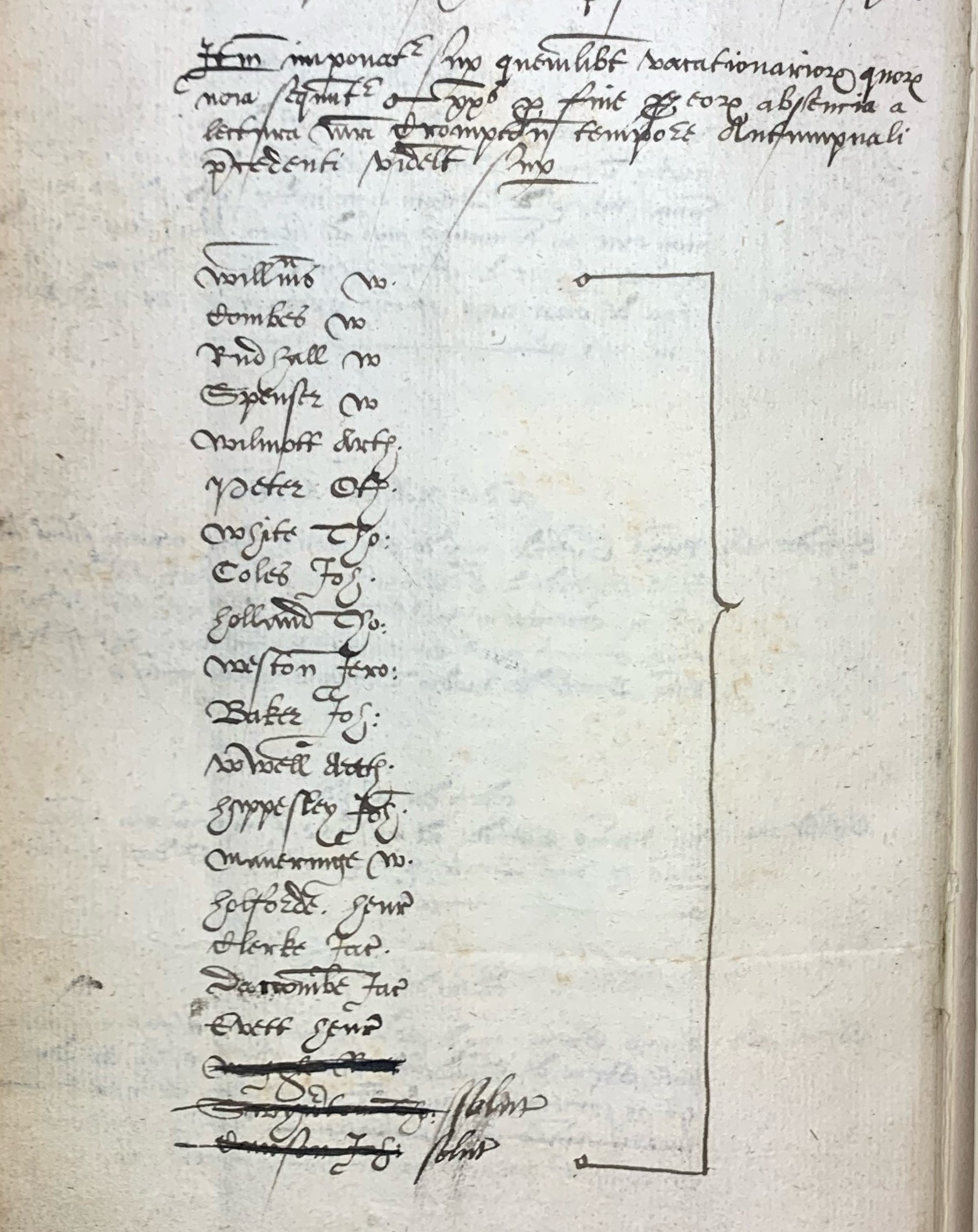

The new Hall appears to have been in use by November 1573, at which point work to convert the old Hall into chambers was underway. It did not take long for members to be censured for breaking the rules of the Inn, with twenty-one students being fined in that very month for missing the Autumn Reading.

List of young men fined for missing the Autumn Reading, November 1573 (MT/1/MPA/3)

Over the ensuing years there are many instances of rules and orders being passed by the Inn’s Parliament which, by their very existence, imply misbehaviour. For example, an order was passed in 1582 against playing dice at Christmas – a popular pastime amongst young people in those days - and then two years later a further order against playing at dice or cards in Hall at any time of year. Archaeological evidence suggests that such orders were followed with little diligence – when the Hall floorboards were taken up for replacement in the 1730s, a hundred pairs of dice, yellowed with age, were found between the joists, having dropped through the floor joints during many illicit gaming sessions.

‘The Gamblers. The Lawyer and the Soldier’, Engraving, 1668-1707

© The Trustees of the British Museum

A ruling was passed in November 1595 against members coming into Hall wearing boots or cloaks – one of many examples of attempts by the Benchers to regulate the dress of the students and barristers. Other minutes are tantalising in their vagueness – such as, in 1590, when it was ordered that ‘Divers gentlemen put out of commons for misorder on Candlemas Night’.

Violence and Swordplay

The first major incident of misbehaviour in Hall that is described in detail in the Inn’s records took place in early 1598 and was particularly violent in nature. The Inn in those days was home to many boisterous young men of a literary bent, who often communicated in poetic form – sometimes penning paeans of admiration for one another, occasionally conveying their companions’ negative qualities with more barbed and satirical verse. It was also common for young men to go about armed – a volatile combination. In the days leading up to the incident in question, Richard Martin, a young barrister, had written a particularly insulting poem about his fellow Middle Templar John Davies – a slight which Davies had taken badly. Indeed, he was so offended that, as the Minutes of Parliament record, he arrived in Hall during dinner, ‘in cap and gown and girt with a dagger, his servant and another with him being armed with swords’.

Leaving his companions at the bottom of Hall, Davies marched up to where Martin was eating, brandishing a stick, described as a ‘Bastianado’ and struck Martin on the head with it until it broke. Having done so, he ran back down the Hall, ‘took his servant’s sword out of his hand, shook it over his own head and ran down to the water steps and jumped into a boat’. The Benchers responded swiftly and firmly to this extraordinary incident – the minutes conclude with the order that ‘He is expelled, never to return’.

Engraving of Richard Martin (MT/19/POR/464)

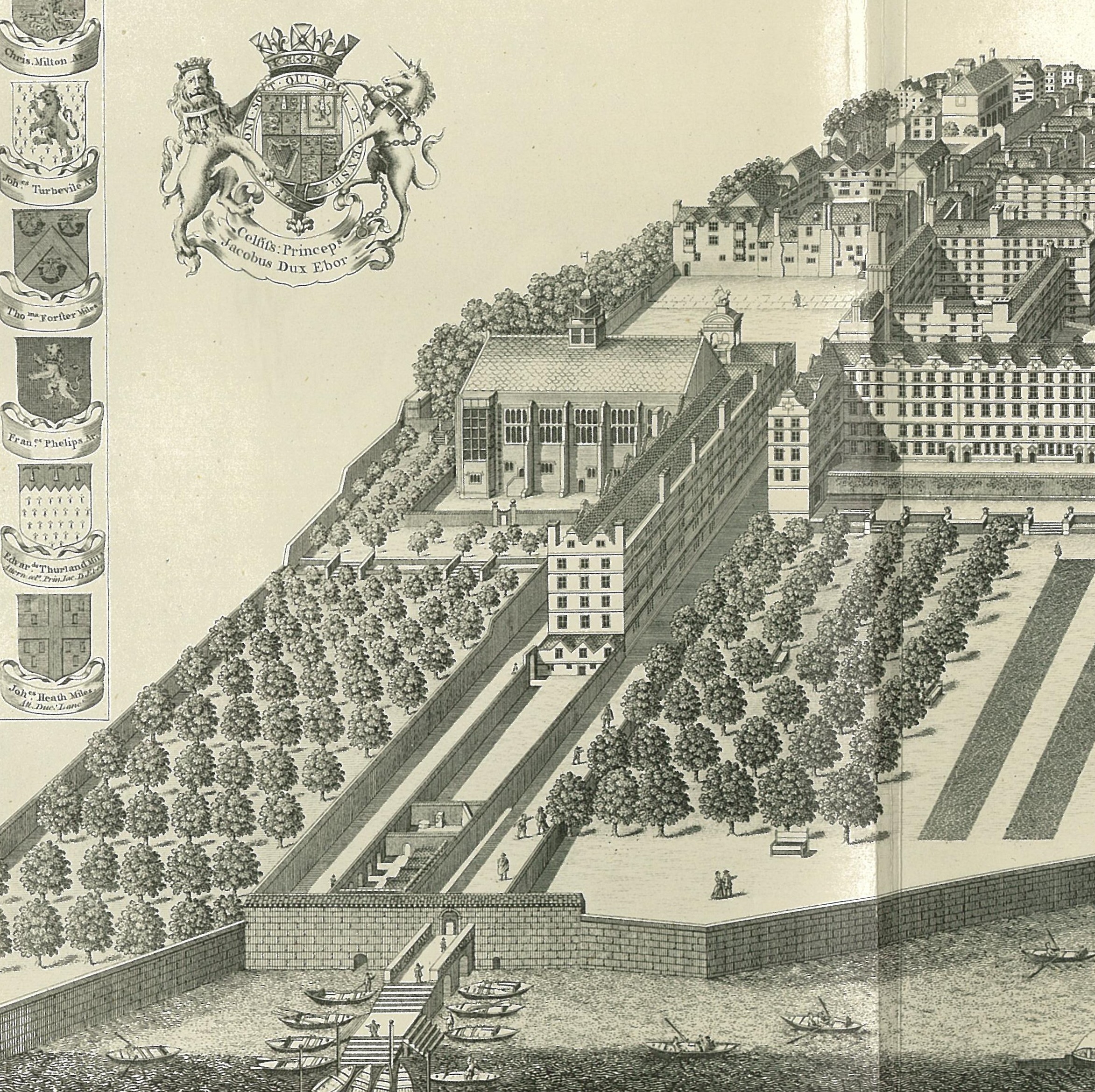

This last order would not, as things turned out, be quite as permanent as had been intended at the time. Having boarded a boat at the Temple Stairs at the bottom of Middle Temple Lane, Davies fled to Oxford, where he spent some years writing poetry, including Nosce Teipsum, a copy of which survives in the Inn's Library. Works such as this caught the attention of the Queen, earning him a position of some favour, and in 1601 he returned to the Inn, making a public apology and being re-admitted. He and Martin both did well for themselves – the latter going on to serve as Recorder of London and counsel to the Virginia Company, and Davies finding favour with the new King James I, who appointed him to high legal office in Ireland.

View of the Temple in 1671, showing the Temple Stairs at the bottom of Middle Temple Lane, from ‘Master Worsley’s Book’

This was by no means the last such violent incident between members that the Hall would see in its first century. In 1610, one Gyles Garton struck Thomas White across the face with his knife at supper time (following an exchange of rude words), and three years later Thomas Rutter punched Mr Bonner in the face before drawing his rapier on him. In 1616, one Benjamin Peere struck Gervys Smyth on the head with his rapier during the Christmas celebrations, and in 1627 Pigott and White quarrelled in the Hall, leading to drawn swords and blows struck. The Inn’s staff got in on the act too, with John Leigh, a Butler, being sacked in January 1620, the minutes recording that he ‘did beat and box Jefferie Jenninges, another Butler, in the entry below the screen in the Hall after supper in the last Christmas holidays’.

Festive Disorder

The period around Christmas, being a time when those members in London over the holiday would customarily dine in the Inn, was a particular flashpoint for general disorder, excessive merriment, and unruly behaviour, much of which was centred on the Hall. While the Benchers frequently passed orders against such festive misbehaviour, and fined the transgressors heavily, successive generations of young Middle Templars were indefatigable in their pursuit of revelry.

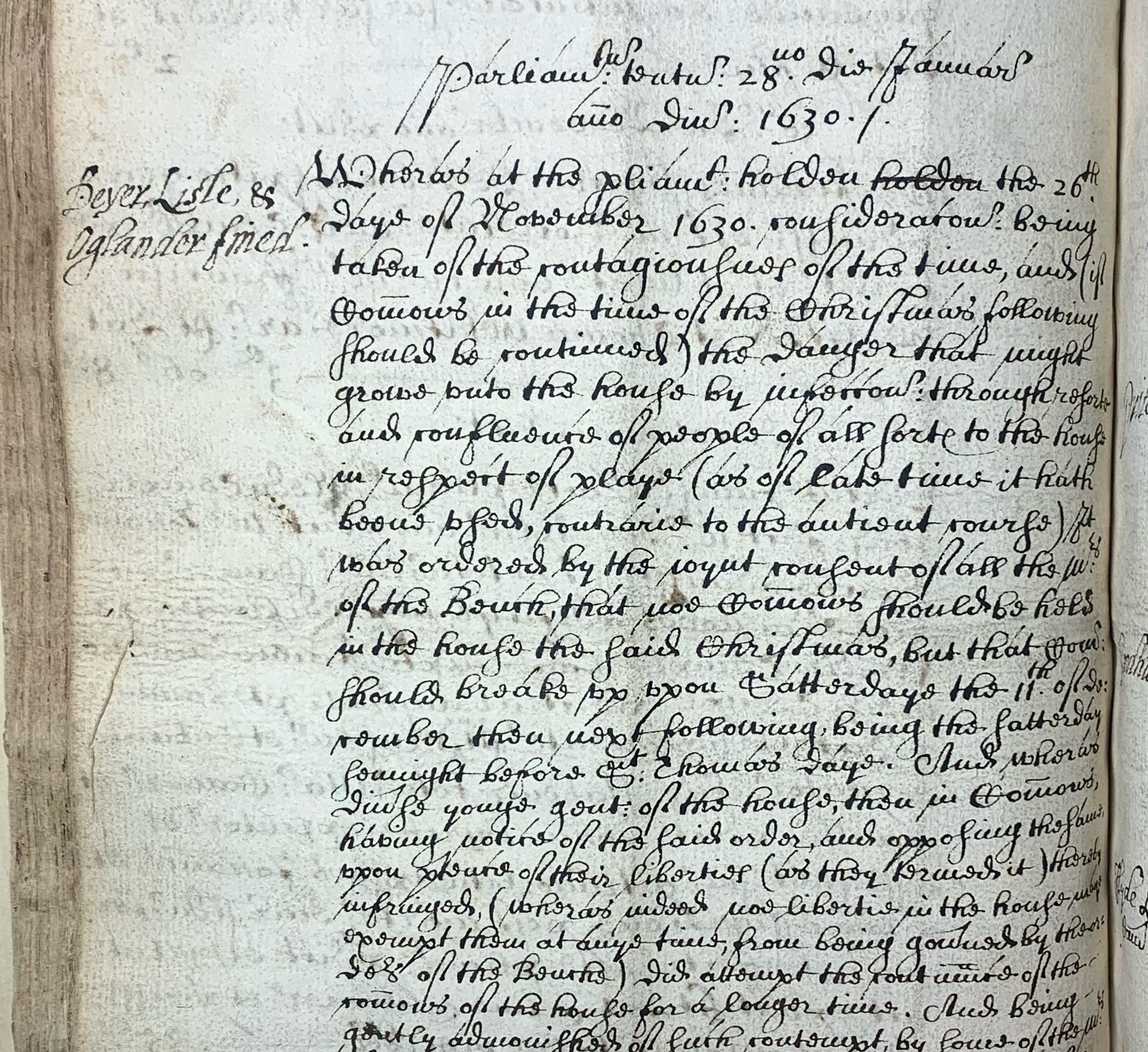

In 1630, during one of several outbreaks of plague in that century, dining over Christmas was cancelled, ‘in consequence of the danger of infection’, with the company to break up between the 11 December and the 15 of January. It is clear from the subsequent minutes that several young men opposed this, ‘on pretence of their liberties being infringed’. The minutes record that they assembled ‘under their own Parliament’ and put the Inn’s Steward into the stocks for refusing to provide them with food. Having subsequently been fined, they appeared at dinner to demand the repeal of the orders against them. ‘This being denied them, they hasted down tumultuously, and calling for pots, threw them at random towards the Bench table, and struck divers Masters of the Bench as they were walking’. Two of these seventeenth century ‘lockdown sceptics’ were committed to the King’s Bench prison by the Lord Chief Justice.

Minutes of Parliament, 28 January 1630, concerning misbehaviour over Christmas (MT/1/MPA/5)

Christmas continued to be a focal point for misbehaviour as the century went on. A meeting of Parliament in January 1639 suggests that the Benchers had lost their patience, noting that in spite of their many attempts to regulate such disorder, ‘insufferable enormities have multiplied’, and record that ‘this last Christmas, to the shame of the Society, far exceeded all preceding Christmases, in admitting base, lewd and unworthy persons in the Hall under a pretence of gaming’ in a festival of misbehaviour going on more than a fortnight. Rather than issuing widespread fines this time, the Benchers focussed their discipline on those who ‘having power in their hands, have not used it to restrain such licentiousness’, expelling the Treasurer of the Bar and sacking the Steward, who was accused of providing the revellers with ‘excess of diet’.

The following November, the Benchers passed the firm order that, for the sake of ‘vindicating the ancient honour of the Society and removing reproach from their government’, no Christmas would be held at all, and that the doors would simply be locked up from St Thomas’ Day until after Twelfth Night.

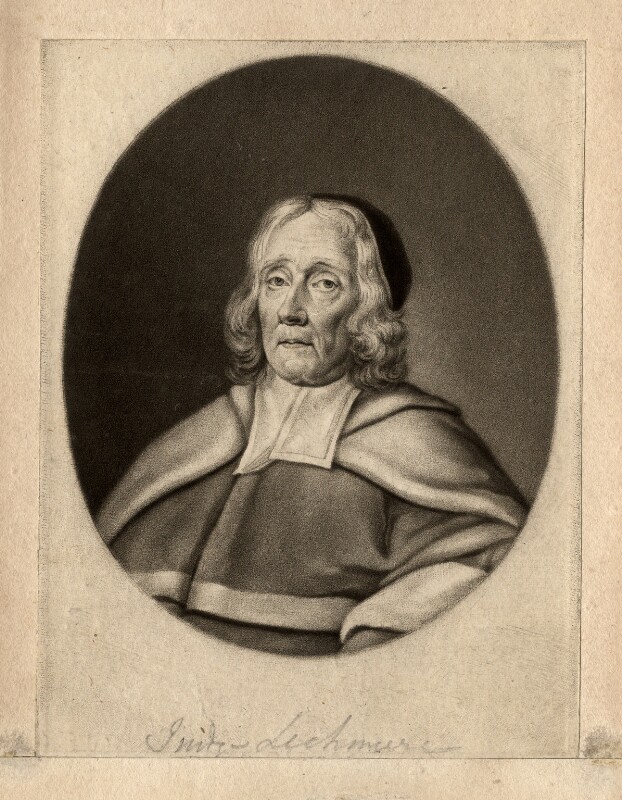

Despite this order – and, presumably, despite the locked door - the fun-loving Middle Templars were still not to be deterred. On St Thomas’ Eve (20 December), members assembled, ‘with their swords drawn in a contemptuous and riotous manner’, and broke the doors open for feasting and entertainments in the Hall, aided by officers and servants of the Inn. One of the prime movers in this was a student, Nicholas Lechmere, who was elected ‘Treasurer Under the Bar’ and was fined twenty marks for his involvement. It does not seem to have done too much damage to his future career, as he would be Called the following year and go on to take the Parliamentarian side in the Civil War, serving as an MP during the interregnum. He was later appointed Lent Reader in 1669 and became a Judge in the reign of William III.

Sir Nicholas Lechmere, by Valentine Green, after George Powle. Mezzotint, Published 1776

NPG D3553 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Records are patchy during the Civil War years – Parliament met infrequently in the early 1640s, much of the Inn’s collegiate and educational activity ground to a halt, and opportunities for misbehaviour and hijinks were few and far between. With the Restoration of the Monarchy and the return of revelry and indulgence, one might have expected an immediate upsurge in mischief, but it took a little time. Indeed, the first recorded infraction of the rules was not until 1668, when John Hanham came into Hall in a white hat, being fined ten shillings for this offence.

However, the floodgates were soon to open once more. Following complaints, the Benchers on 25 November 1670 posted orders against a ‘gaming Christmas’. Somewhat predictably, twelve young men, perhaps seeing this as a challenge, broke into Hall and the kitchen, engaged in extensive gaming, and continued their disorderly behaviour until a week after Twelfth Night. This was the final straw, and the Benchers passed an order that “Doors shall be made to the screen in the Hall”. These are the very doors which are still there today, adorned with carved cherubs and menacing spikes to deter those tempted to climb over in search of revelry.

The Carver’s Bill for Work Done for the Inn on the new doors into Hall (MT/2/TRB/28)

The 1671 doors in Hall today (MT/19/PHO/4/3)

Sartorial Concerns

Sartorial transgressions, which the order passed in 1595 and others had been intended to suppress, continued to trouble the Inn over the centuries. Despite the many rules passed down both by Benchers and the royal government, young members of the Inn often appeared in Hall dressed inappropriately. In 1617, Dowle, Drydon, Bentley and Saunders submitted a petition to be allowed to wear hats in Hall, this having been banned by an earlier order. Their petition was refused, but – not to be discouraged – they came into Hall one evening soon after wearing not only hats but also, scandalously, boots and spurs, refusing to pay the attendant fine. They were expelled for this outrage.

A Seventeenth Century Gentleman sporting hat, boots and spurs (MT/19/POR/188)

A petition from Thomas Bentley, begging to be restored to the Inn following his expulsion, survives in the Archive. He claimed that it threatened his future, being dependent on his father’s pleasure and good opinion, and begged the Benchers to ‘remitt the errors of his youth, and againe to restore him to your noble Society, whereby the perpetuall acknowledgement of your favours shall tye him to a strict observance of all thinges beseeminge the receiver of such desired mercy’. Bentley’s petition was considered by the Benchers, and he was instructed to come to the High Table at dinner time on the first Sunday of the next term to acknowledge his offences. The Minutes do not record whether he complied with this demand – and Bentley disappears from the records from this point onwards.

Petition of Thomas Bentley to be restored to the Inn (MT/3/MEM/7)

While much of the violence and disorder, which had so marred life in Middle Temple Hall in previous generations, had subsided by the Georgian era, transgressions against the dress-codes continued. Problems with adherence to gown-wearing practices were a particular issue, with an order being passed in 1722 that ‘decent and compleat gowns, whole and untorne’ be worn to dinner. This remained a problem a century later, with one W. Boyd being censured by Parliament in 1819 for having removed his gown during dinner and refusing to put it back on, behaviour described in the minutes as ‘contumacy’.

‘The Call Party’ ,showing members dining in gowns, c1860 (MT/19/ILL/F/F2/3)

Etiquette and Manners in Hall

The seemingly more strait-laced Victorian period was also peppered with occasional incidents, particularly relating to interpersonal manners and etiquette. A document survives in the Archive dating from 1861 that records the proceedings of an enquiry into the behaviour of a member, Mr Prendergast, at the most recent Grand Day. Witness testimony from staff in attendance that evening record that Prendergast – described as ‘a little in wine’ – had interrupted a toast with foul language and walked about the Hall ‘talking wildly’, before going up to High Table, pushing chairs off the dais, and throwing himself ‘at full length’ onto the table. He was later involved in an altercation with the Porter’s wife in the robing room, who told him in formidable terms “If you touch me you will have it.” Prendergast was excluded from the Hall and the Library until further order of the Bench.

‘Minutes of Evidence taken before a Parliament of the Honourable Society of the Middle Temple on an Enquiry into the conduct of Mr Prendergast on Grand Day, 24 Jan. 1861’ (MT/3/DIS/5)

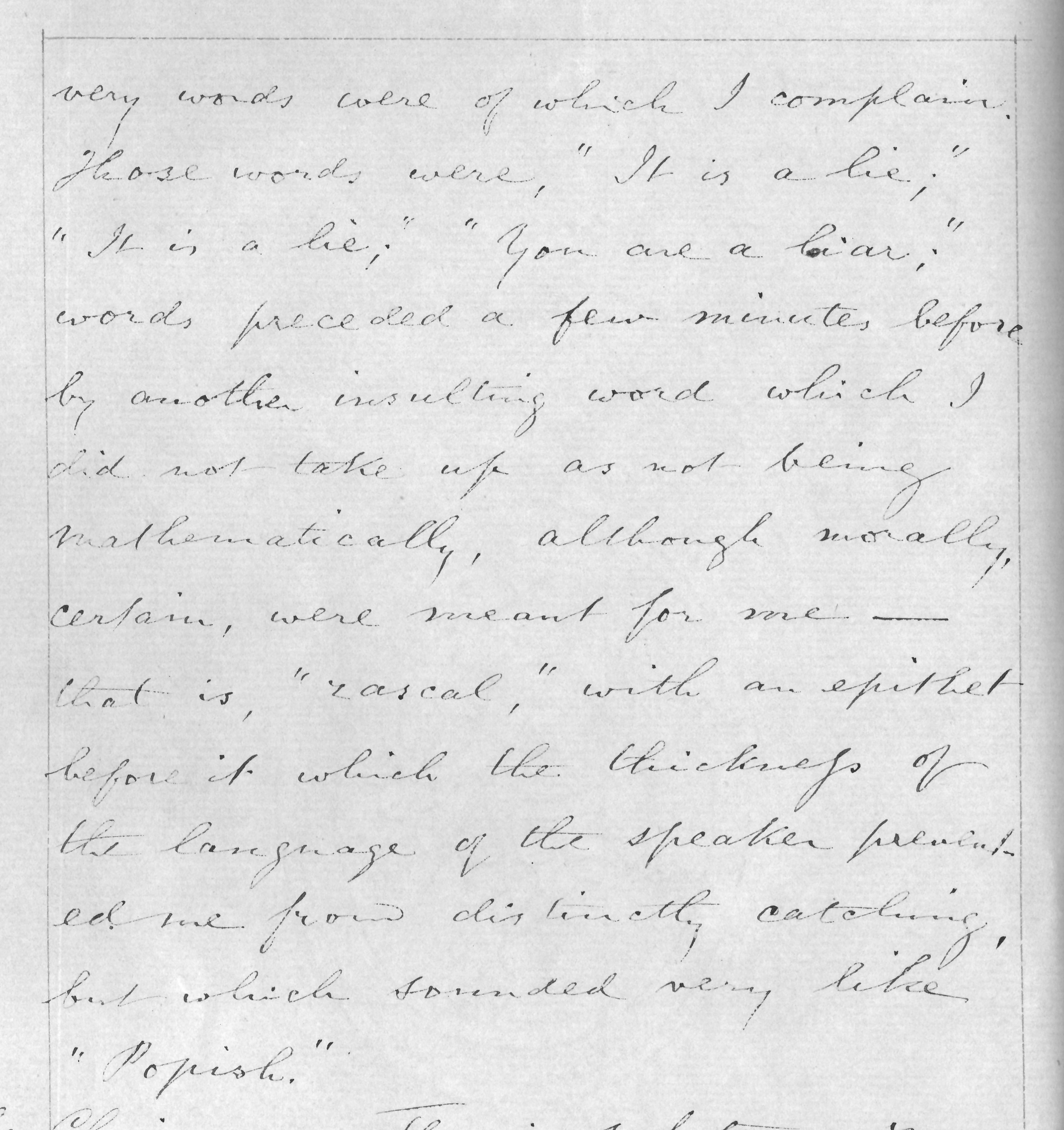

Later that decade, further disciplinary proceedings ensued resulting from poor behaviour in Hall. Thomas Chisholm Anstey made a complaint against fellow Middle Templar John Pulman that the latter had used insulting language at dinner in Hall. Anstey was a Roman Catholic and had served as one of the first Catholic Members of Parliament between 1847 and 1853. Pulman was accused of calling Anstey a ‘Popish Rascal’, of accusing him of lying, and of making highly offensive comments about Roman Catholic priests ‘cheating the peasant out of the best potatoe [sic]’, and worse. The argument which had given rise to such offensive language related to the Irish Church Act, which was passing through Parliament at the time amid great acrimony. After hearing evidence from the two key players and other witnesses present, the Benchers concluded that they could at least be sure that Pulman had accused Anstey of lying, and censured him for the offence. They noted that ‘if the junior members and students in this Hall are not as has been suggested as reticent and as decorous as they were in old times, these faults are likely to be increased if they observe their seniors, members of the Bar, indulging in vituperative expressions & in language which one gentleman would not address to another in any decent society.’

Extract from Evidence in the Case of Anstey vs Pulman, referring to some of the language Pulman was accused of using against Anstey, June 1869 (MT/3/DIS/11)

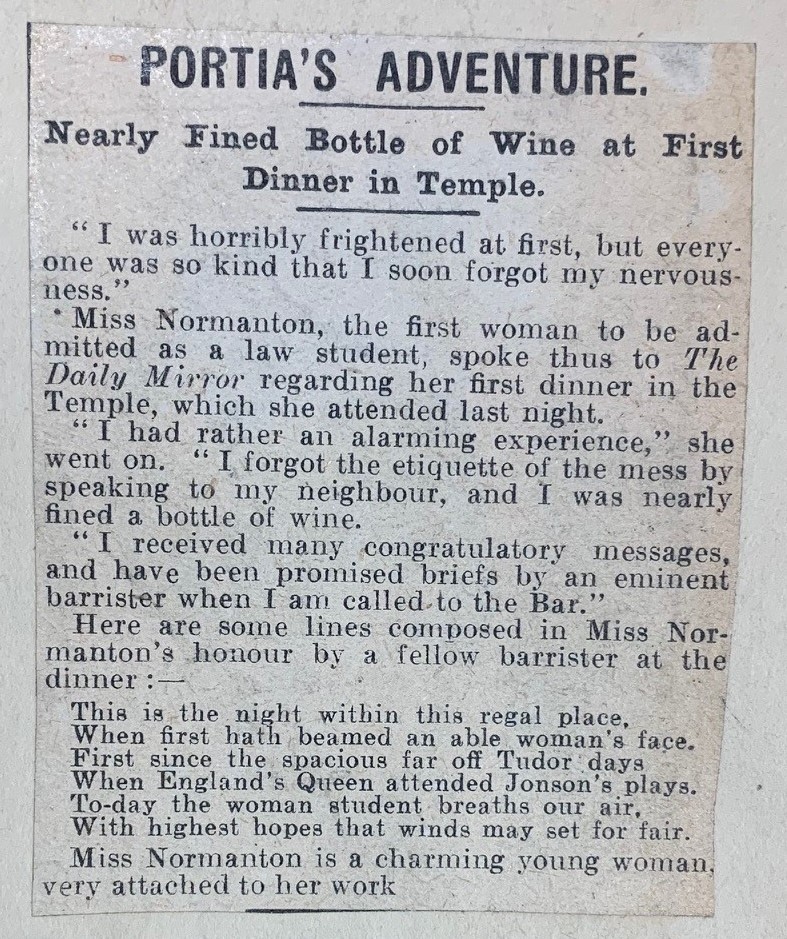

One of the most well-known Middle Templars of the twentieth century was Helena Normanton, the first woman to be admitted to any Inn of Court, and one of the first to be Called to the Bar. She and a group of other female students attended their first dinner in Hall in February 1920, which was widely reported in the press. As well as details of the menu, many newspapers also noted an incident in which Normanton broke the rules. In those days – as is still the case at some dinners today –attendees would dine in a group of four known as a ‘mess’. The convention was that one ought not to talk to anyone beyond one’s own mess – a rule not known to Normanton, who struck up conversation with the person next to her. ‘I had rather an alarming experience’, she told one journalist, ‘I forgot the etiquette of the mess by speaking to my neighbour, and I was nearly fined a bottle of wine.’

‘Portia’s Adventure’, newspaper account of Normanton’s first dinner in Hall, January 1920 (MT/19/SCR/7)

Nowadays, many of the problems which gave rise to strict rules have disappeared – carrying swords into Hall, for example, no longer requires explicit forbiddance, nor is gambling with dice after dinner the disciplinary headache it once was. However, with modern technology, new problems have arisen. The advent of smartphones has called for the introductions of small signs placed sit on the tables at dinner. These remind attendees that the Inn is an environment for members to ‘make connections, exchange views, and learn from each other’.

‘Mobile Free Zone’ sign, 2023

Such innovations suggest that rules and good manners, and their observance and enforcement, will likely always be a feature of Middle Temple life, as they have been for the 450 years of our Hall’s existence. However, we can perhaps be grateful that one need no longer be quite so concerned about the spurs on one’s boots - or indeed the possibility of a junior barrister wielding a wooden club in response to a rude line of verse.