It is almost impossible to walk down Middle Temple Lane, go into Hall or visit Temple Church without seeing a window. Windows are a key part of any building, and their history is intertwined with that of Middle Temple. References to windows frequently crop up throughout the archive, from mentions of the stained glass in Hall, window taxes, repair works and their unwitting participation in misdemeanours around the Inn. This month we will look at the history of Middle Temple, quite literally, through the window.

Glass itself was first invented and developed for architectural purposes during the Roman period, being further cultivated in both the eleventh and seventeenth century to allow for larger panes covering the window ‘hole’. Windows have been used for a variety of different purposes beyond protecting rooms from exposure to the outside while still providing light. For example, when stained glass was invented, it was used to portray biblical stories in churches or highlight the wealth of a building’s owner or patron.

Here at the Inn, there is an abundance of impressive stained-glass work depicting armorial crests and biblical scenes which can be seen in both the Middle Temple Hall and Temple Church.

Armorial Stained Glass Window in Middle Temple Hall.

One cannot miss the armorial stained-glass that adorns the windows in Middle Temple Hall. Many of the coats of arms in the older windows are thought to have been displayed in recognition of members who had donated money to the building of Hall. The Inn has also over the centuries since Hall’s construction commissioned stained-glass windows to commemorate its prestigious members, such as when they paid one Andrew Hall to produce new stained-glass windows in Hall for Sir Robert Hyde, Sir Christopher Turnor (Treasurer 1662) and Sir Geoffrey Palmer (Treasurer 1661), who had all been appointed to high judicial office at the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660. These windows can still be seen today.

Armorial Stained Glass of Robert Hyde.

The stained-glass coats of arms in Hall underwent a reset in 1851, when they were taken out, restored, and replaced. During this time, a proposal was put forward to Parliament to restructure the layout of the stained glass, suggesting that all arms of the Noblemen should be placed in the larger windows, which was passed. In the course of the Second World War, Middle Temple Hall sustained a great amount of damage when the East end was destroyed after a bomb hit another building, hurling masonry through the east gable, shattering the Elizabethan Screen. Thankfully the stained glass had been removed for safekeeping before the war broke out and replaced after the fighting ceased. The glass seen in Hall today is therefore the original.

Image of Call to the Bar in Hall during World War II, showing the destroyed Elizabethan Screen.

The stained glass is absent from the windows, having been removed prior to the War.

Hall was not the only place where one could find armorial stained glass. The Inn’s old Victorian Library (which was unfortunately bombed during World War Two and had to be demolished) had its own set. On 21 December 1859, it was proposed to Parliament that stained glass might be included within the new Library.

The proposition was put forward to Masters of the Bench to gather their thoughts about the issue and establish whether they would be willing to contribute five pounds to the cost in return for having their arms in a window. There is a collection of replies from Benchers in the Archive voicing their views on the issue. A majority of Benchers were happy to contribute financially in return for a stained-glass window, however some voiced their opposition. For example, one Mr Bagshawe pointed out, in his letter dated 3 January 1860, that he was “of opinion that as the arms of the Benchers are already placed in the Hall, it is not expedient to duplicate.”

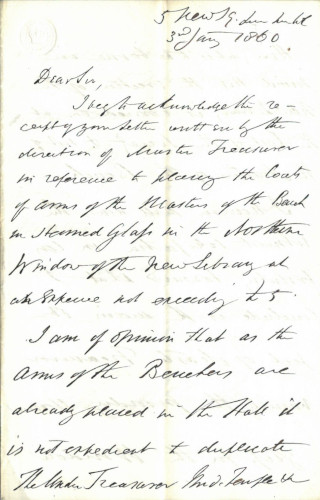

Mr Bagshawe's letter regarding stained glass windows in the Victorian Library [MT/9/LIB/28].

However, on 10 February 1860, it was formally decided by Parliament that the “Great North Window of the New Library, be filled up with stained glass representing the armorial bearings of each Master of the Bench, at an expense not exceeding one hundred guineas.” Sadly, after the war, when plans were made to rebuild the library, now in the Ashley Building, no stained-glass windows were included.

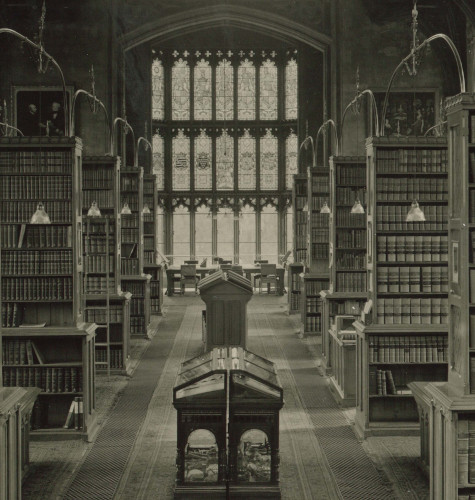

Image showing the stained glass windows in the old Victorian Library.

Temple Church also holds many examples of stained glass in their windows such as the King’s Arms which was created by Baptist Sutton. Sutton was considered one of the greatest glass painters of the period and undertook work for the Inn on many of the heraldic windows in Hall. More recently, the Church celebrated 400 years since King James I signed the Royal Charter (1608), passing the Temple lands over to the Middle and Inner Temples, by commissioning a stained-glass window, known as the ‘Charter Window’, in Temple Church. The window was designed and built by Caroline Benyon with symbols of the two Inns flanking a crown and symbols from the Coat of Arms of King James VI of Scotland and I of England.

Image of a stained glass window in Temple Church.

However, due to the cost of producing stained-glass windows, they are seldom seen elsewhere around the Inn, with chambers and other buildings having plain transparent glass. Nevertheless, even these windows were to become a financial burden for the Inn when the window tax was introduced to England and Wales in 1696 – not to be repealed for another 155 years, in 1851. The window tax required payments to be made to the government based on how many windows a property had, the idea being that this tax would be fairly proportioned to the income of a householder – the more windows, the wealthier one was deemed to be, the more tax one paid

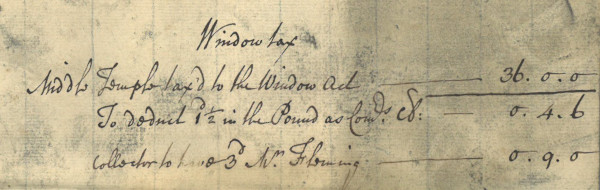

Records in the archive show that the Middle Temple was subject to the window tax over these years, one bill revealing that four pounds and eighteen shillings was to be paid in window tax by the Inn for possessing more than twenty windows on their premises in 1731. Another example, shown in the receipt below, is for a payment of thirty-six pounds made by the Inn in the 1740s to cover the tax.

Receipt for Window Tax [MT-2-XXR-6].

Windows also required constant upkeep to remain at a liveable standard, something that tenant often wrote to the Inn about, organising repairs to broken or damaged windows and frames. Many Orders in the Minutes of Parliament attest to this, such as an Order made on 27 November 1724, in which it was stated that “the windows of every staircase throughout the Society be glazed where there is no glass, and repaired where glass remains, at the joint charge of the proprietors of the several Chambers in the staircases agreed.” Later in 1778, the windows of the Master’s House were given some extended fixing, the builders were asked to “put two new gaged arches over the cellar windows and paint under the windows of the Housekeepers Room.”

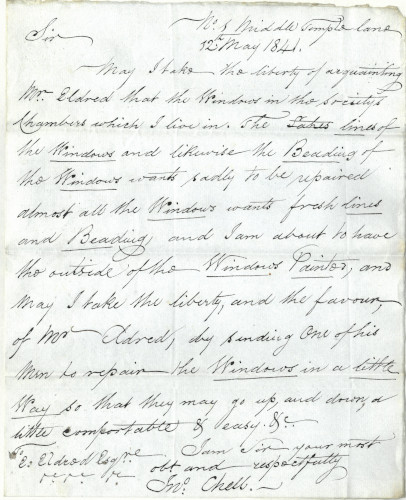

Complaints about the standard of windows also came through to the Inn. For example, one member, Mr Bernhard Smith of 1 Plowden Buildings wrote to the Under Treasurer on the 22 November 1869 to “inform him that the window sashes in his Chambers are in a very bad condition.” Another complaint came through from a Mr Chell in 1841, who wrote that his windows required fixing, asking the Under Treasurer to send through “one of his men to repair the windows in a little way so that they may go up and down a little comfortable and easy.”

Mr Chell's complaint about the standard of windows in his chambers, 12 May 1841 [MT1-LIN].

Alongside this, windows needed to be kept clean, and given the sheer number of windows around the Inn, this was quite a task in itself. As the cost was mostly covered by the Inn (at great expense), there are numerous bills for this cleaning held in the archive. One example of this is the bill pictured below from 26 October 1739 which shows a years’ worth of window cleaning completed by Mr Gatward at the cost of 2 shillings and 6 pence a time.

Bill for cleaning windows in 1739 [MT/6/RBW/68].

Windows were often centre stage in the various misdemeanours committed around the Inn. One rather odd event was at the Cock Tavern where a Barrister had caused a nuisance by throwing offal out of the window into the churchyard, to which the Inn responded by suggesting that a grand grille was to be erected on the outside of the window, covered with wire to prevent any future nuisances.

It was not just offal being thrown out of windows - within Middle Temple Lane, a multitude of records attest to dirty water and waste being poured into the street below, often falling on an unfortunate passer-by! A Mr Kirway wrote to the Inn complaining of the ‘filthy practices’ of the laundress living in the attic above him at 9 Inner Temple Lane, saying that it was the “constant practice of this person to throw out the contents of the chambers utensils.” In 1719, there was an Order passed to prevent laundresses, footboys or other person from “throwing piss, filth and nastiness from upper windows of Chambers in the Inn". This offence could lead to a fine of 10s on the Member whose window it was, payable to the Porter or other officer of the Inn detecting the offence.

Extract from the 1719 Minutes of Parliament ordering against the thowing of rubbish from windows.

Windows were also subject to breakages by carelessness from members in their chambers, one example of this being the actions of William Callow. It was recorded in the Minutes of Parliament that on 25 May 1614, Callow and two others “disordered themselves” in the street, they were “taken by the Watch and brought to the Temple Gate about 2am, they were let in by the Porter, and then broke the windows of divers Benchers and gentlemen both of this Society and of the Inner House.” For this unruly behaviour Callow was expelled, although he was later readmitted to the Inn on the condition that he paid a fine of £5 and discharge the glaziers bill for the broken glass.

Windows are a necessary feature of most buildings and make up a key part of the Middle Temple environment. Their history has often been overlooked in favour of that of the wider edifices and structures of the Inn’s buildings, but as seen here, they are importantly intertwined with much of the Inn’s history and remain a visible and resonant record in the present.