The Middle Temple has admitted male students for at least six centuries, before records begin. However, female students were excluded from admission until 1919, when the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act was passed, and Helena Normanton admitted days later. Over the century since, the admission of women has gradually increased, and in 2020, student entry sat at 58% female to 38% male (4% prefer not to say), a change which has required the Inn and the Bar to adjust and evolve to take account of their presence. This month, we look at how the admission of female students has impacted the Inn – from seating plans to coats of arms – and created a more equal experience for all genders.

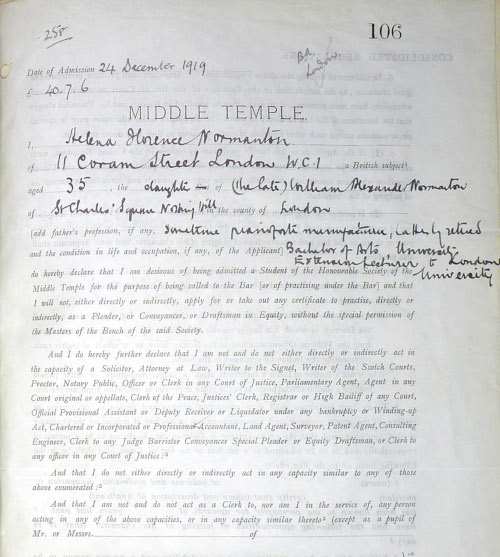

Admission Form of Helena Normanton [MT/3/APA/7].

No female had ever been formally invited to dine in Hall prior to 1919, however, this changed on 11 January 1920 when four female students (including Normanton) dined in Hall to complete the first of the seventy-two dinners required to be Called to the Bar.

This radical event caused shockwaves across the media as multiple newspapers reported on the occasion. The Birmingham Gazette stated that Normanton was nearly fined a bottle of wine for forgetting the etiquette of the mess and speaking to her neighbour, as well as drinking her port before the ‘captain’, but did acknowledge that these were common pitfalls for new students. The Daily Chronicle declared that, regardless of these ‘embarrassments’, there could be “no criticisms on the score of late hours, for dinner was over by 8 o’clock.” Normanton herself appears to have reflected positively on the night, stating afterwards that “I was horribly nervous at first, but everyone was so kind that I soon forgot my nervousness.”

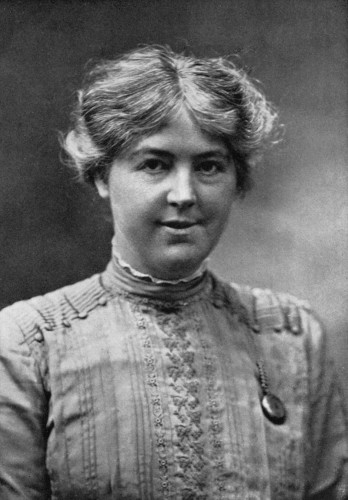

Photo of Helena Normanton.

However, four days after this event, it was ordered by the Treasurer that “all Lady Students lunching or dining in Hall must sit at a table reserved for their exclusive use at luncheon and dinner” excluding them from mixing with men. In 1923, the Inn’s Parliament made the decision that in future women could now bring a guest to dinner on Guest Night, but only if this guest was female. Questions of gendered seating had only slightly improved by 1933, when Standing Order 85 was changed to state that “women students shall sit either at a table set apart for the exclusive use of women members, or at a table set apart for the use of women and women members desiring to sit together.” Thankfully, this ruling was removed, and all students now dine together, irrespective of gender.

The presence of women in chambers had long been a thorn in the Inn’s side – from the 1650s onwards orders were regularly made by Parliament to remove the wives and families of tenants. However, with the admission of women to the Inn, things had to change. In January 1920, The Daily Mirror reported on a barrister’s clerk’s concerns about having women in chambers; he fretted that they would “endanger the lives of the solicitor’s clerks who bring her briefs by placing flowerpots on the windowsills of houses in Middle Temple Lane” and that women wouldn’t leave their law reports in the shabby cloth bindings but “will have them rebound in pink half-calf.”

Garden Court Chambers.

Such unenlightened views were widespread and were the tip of the iceberg in terms of the challenges and sexism faced by women in the profession for decades to come. Although women did work and live in chambers, it would not be until 1974 that a woman became a Head of Chambers, when Barbara Calvert became the Head of 4 Brick Court. Women are now a regular fixture in chambers, and, despite the fears, there is no record of anyone ever having been injured by a flowerpot!

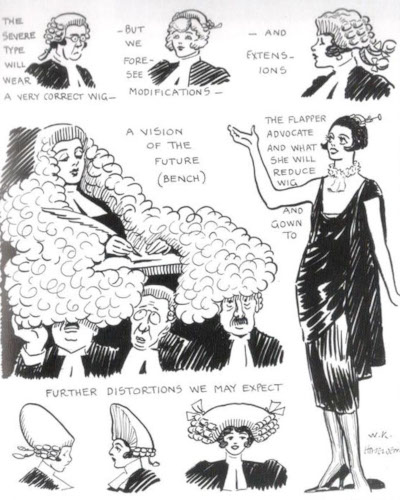

Another issue, apparently at the forefront of public concern, was whether women would be able to wear wigs and what dress code they would follow. A magazine cartoon created in 1921 shows its hilarious prediction of how the first female barristers would have to modify their wigs.

Cartoon predicting how the first women barristers would modify their wigs. © Copyright of www.legalcheek.com.

Many of the concerns revolved around the length and styles of women’s hair, leading to suggestions that female barristers should instead “wear a special type of a wig, or completely different head-wear, such as a biretta, turban or toque.” The issue was put to rest in 1922 when a Committee of Judges and Benchers in the Inns of Courts decided that women barristers should wear ordinary barrister’s wigs, albeit only if their hair was completely covered and concealed.

Due to there being no specialised clothing for female barristers, the Manchester Dispatch reported in 1922 that “men and women alike wore the regulation wig and gown of the barrister. It was hard indeed to distinguish the women from the men.” It was not until 2020 that a legal outfitter dedicated to making court wear for women was founded. The very aptly named organisation, Ivy & Normanton, now enables women to wear clothes specifically designed to fit their body. (https://ivyandnormanton.com/)

Even as women had more of a presence at the Inn, they were still being pushed aside from the mainstream. In 1936, Helena Normanton presented Middle Temple with a large square silver inkstand, derived from a salver made in 1721 by a Huguenot silversmith, and inscribed to the memory of King George V, during whose reign the English Bar was opened to women. When donating this to the Inn, Normanton requested to the Under Treasurer that the inkstand be used by newly Called barristers when signing their names. She was rebuffed with a reply which stated that it would instead be “place in the ladies’ room in the library”, to which Helena retorted “I think that quite possibly the Masters of the Bench do not realise the extremely narrow circumstances of some of the women members of the Inn."

Ink Stand donated by Helena Normanton.

As well as making waves as students and later as practising barristers, women also began to play an active role in societies and general life at the Inn.

One early example of this was in 1923, when the Hardwicke Society, the foremost debating club for students and barristers with over 2,000 members, admitted its first female member, Miss Ida Duncan, after “a persistent body of pro-feminists” passed the change by a majority of four, in a house of 30 members. This event was reported by The Morning Post who went on to state that “just as the Circuit and the Old Bailey Bar Messes have to accommodate themselves to changing circumstances, the Hardwicke will have to mend its way and discard all that is left of the rough-and-ready manners born of its origin in coffee-house and tavern.”

Women members at Middle Temple also played an important role during World War II, which was recorded through a written account requested from Helena Normanton by the Ministry of Information. Normanton notes how all women aged up to sixty years of age were liable to assist in Civil Defence, such as fire-watching, and gives further examples of Middle Templars such as Beoroe Bicknell, who worked guarding the Inns of Court, and Florence Earengey, who became an Air-raid Warden in 1938. Helena also states how many of the younger women Called to the Bar at Middle Temple were serving across the world in uniform, showing how women barristers made an invaluable contribution to the war effort.

Women also got involved in student events at the Inn, for example, participating in the annual revels event, an ancient tradition in which students perform plays, comedy sketches and sing songs. The images below show female students joining their male counterparts on stage to entertain fellow members, c.1970.

Women participating in a revels performance [MT/19/PHO/2/6/1].

More recently, in 2012, the Temple Women’s Forum was established as a collaboration between Middle and Inner Temple to “encourage and support women throughout their careers, so as to increase retention within the profession.” Their first event saw over 400 women in law gather in Hall, the largest number of women to congregate in that space in the Inn’s history. They host events such as Networking Garden Parties and a range of panels which has bought women of the Bar together, while continuing to help make great strides for females in the profession.

Photos from events hosted by the Temple Women's Forum [MT/1/NEW/56].

The excellence of women students began to be recognised and rewarded in the Inn when in 1947, the Chrystal Macmillan Memorial Prize was founded and gave a prize for the female law student at the Middle Temple who scored the highest in the Bar Finals examination. Now awarded (as the Chrystal Macmillan Prize) to a Middle Temple student “at the discretion of the Scholarships and Prizes Committee", it continues to honour Macmillan’s memory, a Middle Templar and graduate of the University of Edinburgh, who was Called to the Bar in 1924 and was a passionate suffragette.

Photo of Chrystal Macmillan.

Although women continued to establish themselves in the world of law and achieved great successes, it was not until 2001 that a female Reader, Barbara Calvert, was appointed, and the first female Treasurer, Master Dawn Oliver, in 2011. It is a centuries-old tradition that the coats of arms of Readers and (since the 1980s) Treasurers of the Inn are displayed on panels in Hall and the Bench Corridors. As heraldry treats women differently to men, the women’s panel designs break the running of men’s shields, as the arms of most female Readers and Treasurers are displayed on a lozenge with no crest, as illustrated below.

Armorial Panel of Linda Elizabeth Sullivan, Autumn Reader 2009.

It is not only through their presence on the armorial panels that women have made their mark on the Inn’s walls. In 2018, Master Dawn Oliver became the first (non-royal) female Middle Templar depicted in a painting hanging in the Inn. Painted by Emily MacDuff to commemorate Master Oliver’s appointment as the Inn’s first female Treasurer in 2011, it currently hangs in the Parliament Chamber corridor.

Portrait of Master Dawn Oliver.

The introduction of women to the Middle Temple caused great shockwaves and necessary changes to be made to an institution that had previously been dominated by the interests and priorities of men. Although it has taken time, and there is still more work to be done, great progress has been made towards creating a more equal Inn which respects all genders that are admitted and Called to the Bar.