Different seasons bring about a variety of changes, primarily in the weather, which has a knock-on effect for all areas of life in and around the Inn. Winter, for example, brings with it a colder climate which historically has changed how people went about their daily life at Middle Temple, from frost fairs, the arrival of snow and struggling to heat freezing chambers. Topically, for December’s Archive of the Month, we will look at how winter has played it part in life at the Inn.

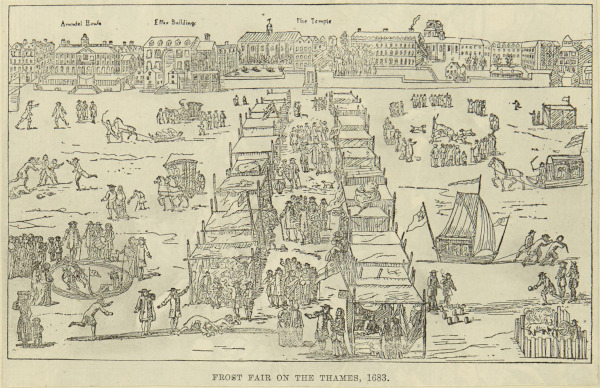

The ‘Little Ice Age’, a period of regional cooling, occurred from the 16th-19th Century, during which there were many occasions when the river Thames froze over. Enough ice was created to allow pop-up ‘Frost Fairs’ to appear on the river; these events involved traders setting up market stalls to sell goods, food and beverages. Not only this, but other activities were enjoyed, such as playing nine-pins, visiting the printing booth, and eating mutton or ox roasted on the ice. Before the Embankment was built, the Temple grounds backed onto the river Thames, meaning that these Fairs became a part of life at the Inn.

Print of Frost Fair on the Thames, 1683 [MT/19/ILL/D/D8/16].

Not to miss out on making some quick money, souvenir stores appeared to sell memorabilia of the occasion. One such purchase that could be made was a silver spoon from the 1684 Frost Fair. This spoon is inscribed with “this was brought at the faire kept upon the Midle of ye Thames against ye Temple in the great frost on the 29 of January 1683/4”, implying that it was sold just outside of the Inn.

Silver Spoon sold at the 1683/4 Frost Fair © Museum of London.

During the severe winter of 1739, which resulted in a Frost Fair, £10 was provided by the Inn to “such poor Watermen plying at the Temple stairs as shall assist in cleaning and carrying away the dirt, filth and ice lying in and about the Courts and places of the Society.”

The freezing of the Thames had further effects on the Inn, as it meant that when fire broke out on the evening of 26 January 1678/9 at Middle Temple, there was no water available to extinguish the flames. Because of this, beer from the Temple cellars had to be used instead! Roger North, a member of the Inn, wrote that “the water froze in carrying and choked the engines with the ice that continually grew in it. Water was let down from the street but froze and stopped its current.”

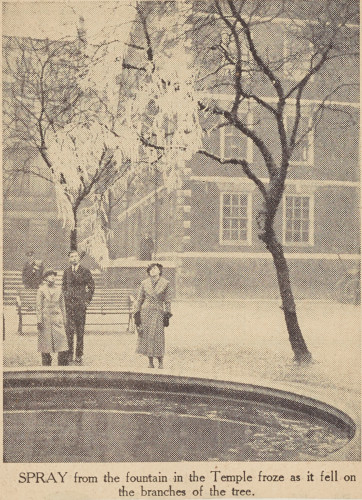

Later, in 1895, freezing winters still prevailed and halted the water supply. On 24 February, Mr H. Rushworth wrote to the Inn concerning the lack of water supply in his chambers at 4 Brick Court. Freezing water has also produced phenomena at Temple Fountain when the cold weather caused the spray to freeze in such a way to create an ‘ice tree.’ These occurrences were reported in newspapers, for example on 1 March 1845, the Illuminated Magazine reported of the Ice Tree, stating that the event “attracted the notice of several persons; but in the midst of their admiration, the tree broke down with the weight of its incrustations.” Again in 1936, the Morning Post included a picture of the fountains spray as ice, which “froze as it fell on the branches of the tree.”

Left: Engraving of 'Ice Tree' from 1845 [MT/19/ILL/E/E4/12] Right: Picture of 'Ice Tree' from 1936 [MT/19/ILL/E/E4/37].

Today, when winter hits the Inn, one is able to turn up the central heating and warm the temperature inside the buildings – however, this hasn’t always been the case. Unless heated by an efficient fireplace, rooms at Middle Temple could become a chilly place in which to work or live.

Fires were key to keeping people warm before modification. Middle Temple’s Elizabethan Hall originally had a large central hearth to heat the room, and the central chimney space remains testament to this, even after the fireplace was removed in the 19th Century. However, having an open-hearth fire in Hall came with its own risks. The Minutes of Parliament in 1695 discuss the how one Butler, John Blyth, was attacked in Hall by two, subsequently expelled, members who “burnt his periwig in the fire in Hall.”

Image of the open hearth in Middle Temple Hall [MT/19/ILL/D/D2/11].

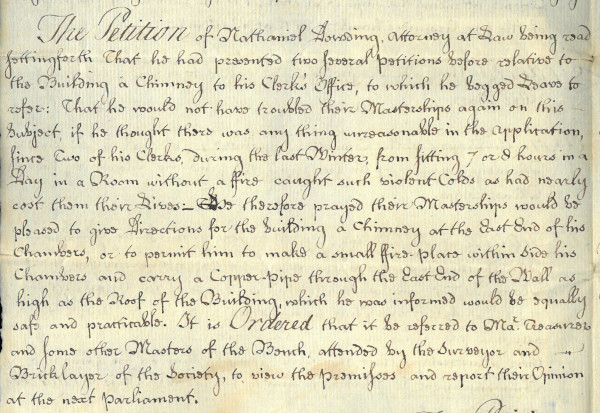

Fire was also needed to warm Barrister’s chambers, however, many of their rooms lacked access to chimneys. The Archive holds many letters from Members complaining about the cold conditions they suffered in their rooms. One example is from a Mr Nathaniel Dowding who petitioned the Inn in 1782 requesting permission to build a chimney in his clerk’s office, which was initially rejected. Dowding states that he found the refusal unreasonable and petitions again arguing that “two of his clerks, during the last winter, from sitting 7 or 8 hours in a day in a room without fire caught such violent colds as had nearly cost them their lives.”

Petition of Nathaniel Dowding [PPA 25 January 1782].

This sentiment had already been displayed in February 1745, when two Barristers, Edward Green and Nathaniel Lloyd, spoke to Parliament stating that due to there being no chimneys on any of the chambers, it rendered them of very little use in the winter months. The two men asked for permission to erect chimneys at their own expense which was approved by Parliament on 9 May 1746, where the minutes state that the proprietors of No. 6 Pump Court Chambers may build chimneys, on condition of their employing the Society’s workmen.

Lantern Slide of Fireplace and Hearth [MT/19/SLI/79].

Although members were very much in need of chimneys to warm their rooms, it appears that Parliament often wasn’t so supportive of these wants. For example, it was recorded in the 1742 Minutes of Parliament, “that part of the Chambers are very incommodious for want of a fireplace in their studdys.” But chimneys themselves were not without issue. An unfortunate incident occurred in 1692 when Mr B. Tonstall came to Parliament asking for a repair to his chimney as the hearth of the chamber above him had fallen into his room!

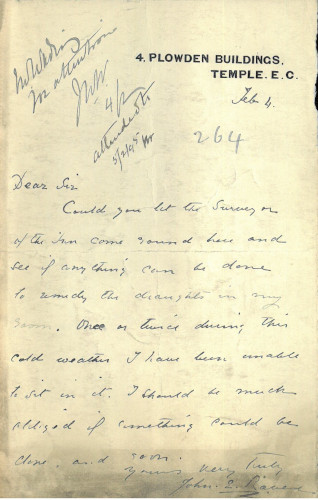

It appears that little changed in regard to the warmth of chambers in 150 years as on 5 February 1895, a Barrister, Mr John Raven, wrote to the Inn asking if anything could be done to remedy the draughts in his room. Raven states that because of the cold weather he has been unable to sit in his chambers. We hope that today, with the benefits of central heating, our readers are rather warmer than Raven!

Letter written by Mr. Raven [Box XXIII - BUNDLE VI – 9].

It wasn’t just members of the Inn who had to endure the perils of cold weather, staff also were subject to the harsh, cold conditions of the Inn during winter. In particular danger were the watchmen who often worked outside in cold conditions.

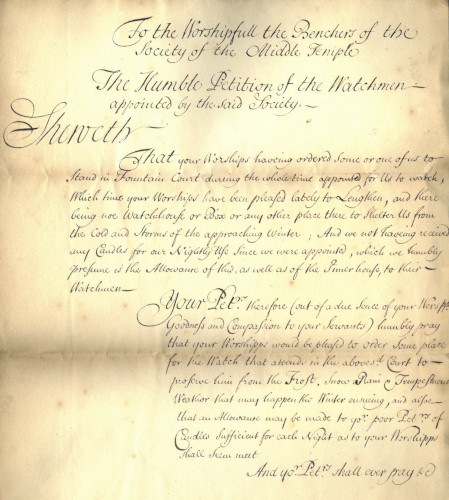

In the 18th Century, a petition was written out by the Watchmen of the Society stating that they had “no[e] watchhouse or box or any other place there to shelter us from the cold and storms of the approaching winter.” The watchmen ask that a cover is erected for them to protect from “the frost, snow, rain and tempestuous weather that may happen this winter evening.”

Petition from Watchmen, 18th Century [Box V - Bundle XVII - 10].

During the severe winter of 1790, the watchmen wrote another petition to the Benchers requesting a bounty from them for their work, similar that which they had received the year before, when the winter hadn’t been as severe as the one they were now experiencing. The workload for other staff members also increased during winter months, for example in 1716, the Gardener and Porter stated to Parliament that last winter, they had been at “unusual charge and trouble in cleaning and clearing the several Courts of the House of great quantities of ice and snow.”

Snow by Temple Church [MT/19/PHO/12/2/7].

Staff also experienced the cold indoors. Mr. William Cox, the first Keeper of the Library, petitioned in 1653 for a fire to be placed near him when working there due to the age and weakness of his body. Later in 1744, an Under Porter of the Inn, Henry Jeffs wrote to Parliament that his “little room facing the pump in the lane was so excessively damp and cold, it had impaired his health.”

The cold weather often led to members deciding to leave the country and take a winter break outside of London for health reasons, with numerous petitions regarding this being stored in the archive. One example of this is in 1886, when a Frank Dobson shared certification from his medical attendant, stating that it was essential he didn’t spend another winter in England. Another record in the archive shows a petition from Louis Benoit Ogé Remy Ollier in 1868 asking to be Called to the Bar so that he may relocate, for the importance of his health, to a warmer climate. Having come from Mauritius to London, it is understandable why he would not want to face the cold weather at Middle Temple.

Middle Temple Fountain on a cold and snowy February morning [2021].

It is clear to see that, during the winter months the weather has for many years had an effect on daily life at the Inn - whether due to plummeting temperatures or to changing and challenging workloads for staff. While today the Thames no longer freezes over, and we have central heating to keep us warm, it is not hard to imagine just how cold and frosty winters at the Inn could be for members and staff of the past.