Middle Temple Lane may seem a quiet thoroughfare connecting the busy Embankment, Strand and Fleet Street, but for hundreds of years it has been a hub of activity for students, members, and laypersons living and working within the vicinity. Where there are people, services are required, and the Inn is no different. Throughout its history, the Lane has been host to a variety of shops such as stationers, peruke makers (wig makers), hatters and of course, taverns. This month we investigate the history of these establishments through the records in the archive.

Shops

The shops in and around the Inn catered specifically to the nearby consumers, so there was therefore an abundance of peruke makers, bookshops, barbers, and stationers situated on the Lane. Since the 1500s there are record of the existence of shops in the archives, from rent charges to lease agreements, and disagreements between shopkeepers. By 1775, there were some 15 shops in the Inn, including a Hatter, Seal Engraver and Shoemaker, whose shops were let out to them at a yearly rent.

Not everyone welcomed the shops, and there was a dispute in 1695 when some Barristers and Students of the Middle Temple wrote to the Benchers a list of complaints, one which included the issue that the Benchers had “permitted shops and huts to be built to the annoyance and scandal of the Society.” However, this complaint was rebuffed by the Benchers who argued back that the shops were “inhabited either by servants and officers of the Temple, or by tradesmen proper and useful to the Society, such as stationers, booksellers, watchmakers, tailors, and barbers. They give no instance of any shop being an annoyance or scandal.”

The Strand from the Corner of Villiers Street. © The British Museum.

Not all shops on the Lane operated in purpose-built premises, with many functioning from chambers, a common enough occurrence that in 1719, Parliament ordered for chambers not to be used as shops without special leave from Parliament. This was taken further in 1857 when it was ordered that in all cases of letting chambers to a person not a member of the Society, a bond was to be taken stating that “no such tenant shall carry on, or permit to be carried on, in the chambers let to him, any trade, business or calling whatsoever.”

Shops were not just situated on the Lane: many also lined the walls of the Church, as this image below, from 1860, shows. The Minutes of Parliament discuss the building of shops by the Church, one example of which is of the stationer Thomas Morse who was granted the lease of his shop “in the Churchyard near the Cloisters” for twenty-one years in 1680. Later in 1697, Robert Podmore, also a stationer, was granted a lease for “his little shop by the Church” under the instruction that the was “not to enlarge the shop.”

Temple Church and Shops, c. 1860.

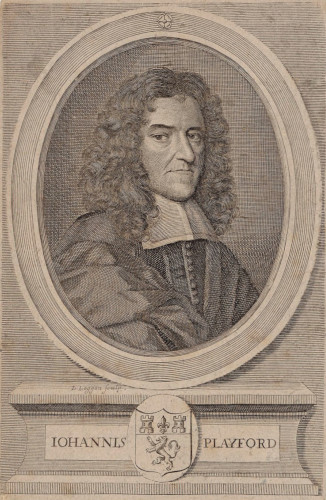

One shop by the church was owned by John Playford, a bookseller who published books on music theory and instruction on several instruments, who opened a shop in the porch of Temple Church during the mid-1600s. His shop was frequented by many musical enthusiasts and notable Londoners such as Samuel Pepys.

Engraving of John Playford.

A company which began its life at Middle Temple and is still in operation today, is Jones and Yarrell. The company set up shop as a bookseller and newsagents in a small room on the Lane c.1734, operating there until 1893 when they moved to Essex Street, growing to become the largest corporate news delivery specialist in the UK today. It was recorded in the Minutes of Parliament on 25 October 1734 that “Robert Jones, Stationer, to have a Lease of the shop in Middle Temple Lane now occupied by him, for such term and under such Covenants as Mr. Treasurer shall think most for the service of the Society.”

Original site of the Jones and Yarrell site, taken in 2021.

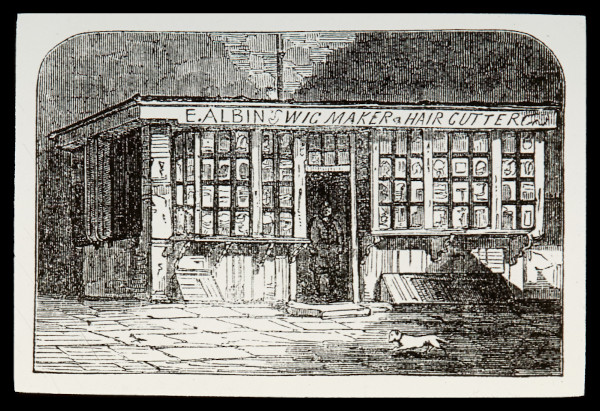

A shop whose presence was in demand from barristers for their court attire was that of a peruke-maker (wig maker). There are many references to these shops in the Minutes of Parliament, and one which stood for many years, a prominent fixture at the top of Middle Temple Lane, was Albin’s Wig shop.

Lantern Slide the shop of E. Albin, wig maker [MT/19/SLI/2].

Of course, not every shop at the Inn was above board, for example in 1638, stationer Richard Meighen complained of a breach made to his shop by Henry Byrd, a glover. Meighen claimed that Byrd had pulled down a stone wall between their shops in Temple Gate, thereby exposing his books to danger, and encroached upon his shop by thrusting boards thereinto to widen his own shop. The dispute was resolved through an order from the Under Treasurer that Byrd was to pay Meighen 40 shillings in compensation for the removal of the wall.

Later in 1716 there is record of a shop located on a passage running by Garden Court which was ordered to be searched by Parliament “to see if there be not ale and brandy sold there or other use made thereof which is dishonourable and of inconvenience to the Society.” It was later found, in 1719, that alcoholic liquor was being sold from the cellar, it was subsequently ordered to be filled up, no more liquor sold in the shop, and all signs over or on the shop were to be obliterated.

Minutes of Parliament, 1 June 1716. [MT/1/MPA/7].

Following this incident, in 1720, a Mrs Russell was ordered to remove her stall selling fruit under the Cloisters because she had encouraged a man, who pretended to be a Porter of the Inn, in “his insolent behaviour towards the authority of the Benchers.” Mrs Russell obeyed this ruling, but later in 1733, “the woman who sells fruit under the Cloisters" (possibly Russell) was "to be removed forthwith", and no one was "to be allowed to sell fruit, oysters or anything else" in the Inn.

Today there are fewer shops on Middle Temple Lane, although many shops serving the needs of lawyers survive on Fleet Street and the Strand. More recently, the Inn itself established a shop selling official Middle Temple Merchandise, ranging from Christmas decorations to cufflinks, from which the profits are put towards the Hardship Appeal and Scholarship Funds.

Teddy Bear on sale at Middle Temple Shop.

Taverns

Outside of study and work, members of the Inn have always enjoyed having a place to go and enjoy their leisure time – for some this was a visit to the local tavern. Thankfully for the tavern-goers, they didn’t have to leave the walls of the Inn as many had doors which led through from the Lane straight to the bar. Unfortunately, a consequence of this was that after ‘a few too many’, unruly drunken behaviour could sometimes spill out into the Lane.

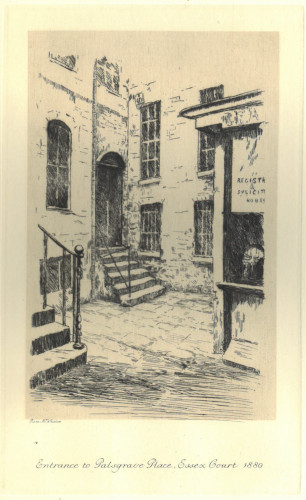

One tavern which opened out near the Lane, into Essex Court, was The Palsgrave’s Head Tavern situated on the Strand. However, due to some unruly behaviour from patrons, an Order from Parliament came through on 21 June 1650 stating that “a lock be fitted on the gate in Essex Court leading through to the Palsgrave’s Head tavern and that the porter of the Society keep the only key. The vintner and others are permitted passage from 6 o’clock in the morning till 9 o’clock at night from 25 March to 29 September and from 7 o’clock in the morning till 8 o’clock at night from 29 September to 25 March, providing order is kept.”

Entrance to Palsgrave Place, Essex Court, 1880. ]MT/19/ILL/F/F11/8].

However, good order must have been kept by the tavern’s patrons, as in 1666, it was at the request of ‘divers gentlemen’ whose Chambers were situated in Essex Court, that the Palsgrave Tavern’s door was opened up in term time which was approved by the Inn’s Parliament, unless there was cause to the contrary.

The existence of the above passage caused conflict when the Rose Tavern, situated outside of Temple Bar with a garden behind it, which was divided from the Inn by only a brick wall with a door in it and passage into Essex Court, wanted to open an entrance to the Lane. The tavern was run by a Richard Clarke, who felt that the blocking of this door was prejudicial to his business, especially as the Inn allowed The Palsgrave Tavern to have an open door leading to Essex Court. In fact, the Earl of Arlington wrote to the Benchers of the Middle Temple, on the command of the King, that the door was allowed to reopen as if it were a private house.

Letter from Arlington to the Bench, 27 October 1670 [MT/6/RBW/2].

Another tavern which backed onto the Lane, was the ‘Divell Tavern’, which was frequented by notable people of the day, such as Samuel Pepys and Samuel Johnson, until it was demolished in 1787. The plaque at 2 Fleet Street, below, commemorates it. During its time, the Tavern was subject to the Inn ordering the blocking of its access to the Lane, an Order prescribed “the walling up of the door lately made from the Divall Tavern into the Middle Temple Lane.”

Plaque showing the site of the Devil Tavern at 2 Fleet Street.

As has been explored in this article, the Inn has had a very diverse range of shops and taverns operating within its walls over the past five hundred years. Shops have played an important part in shaping the Lane, with chambers transitioning to shops and back into chambers over time, and the direct access through passages and doors to nearby taverns allowing members to enjoy their free time with ease.